マリオ・カルポ: アイデアは50年代のものですが、建てられたのは60年代のことです。そして市場に出回ったのは70年代のことです。バービカン・エステートが竣工したのは、チャールズ・ジェンクスが『ポスト・モダニズムの建築言語』を発表したほんの数ヶ月前のことですから、ちょうど転換期だったのでしょう。1977年以前には、バービカンは未来にあり、1977年には過去のものとなってしまった。

バービカンは愛されていましたが、同時に憎まれてもいた、と。

モダニズムの精神。戦後技術社会の想像力が生み出したフランケンシュタイン的怪物。それは、個人住宅など存在すべきではないと強く提唱していました。その代わりに、大量生産されたプレファブの集合住宅が、標準的生活のテンプレートとして機能するはずである、と。それは、高密化する大都市の現状への単なる現実的な対応にとどまるものではありませんでした。マスプロダクションやスケールメリットのイデオロギーとして、近代的男性、そして女性へと差し向けられたものでした。それ自体が標準的なプロダクトとしてね。

バービカン・エステートは、モダニストのイデオロギーの成果なのです。その広大なスケール、反復、剥き出しのコンクリート、そしてセントラルヒーティング。50年代的な信条が明確に表現されています。比較的高価な集合住宅として、上位中産階級をターゲットにしていましたが、美的にも雰囲気的にも時代に沿ったものではなかったのです。それが、昔の世代の夢の具現化として認識され始めたのは、1970年代の後半からです。

今では多くの人が、2000戸の「手頃なおうち」の並んだ平凡な建物だと思っていますし、そうやって撮影したり、研究したりしています。でもね、見当違いなんです。ソーシャルハウジングの類いでは全くないのですから。

なぜ、そのように理解されてしまっているのでしょうか?

ブルータリズムのことを、ソーシャルハウジングのスタイルだと勘違いしているのでしょう。コンクリートで建てられていますから。だからバービカン・エステートは学生にも人気がある。ただそれも、国が本当にソーシャルハウジングを建設していた時代へのノスタルジーに過ぎないのだと思います。1979年にマーガレット・サッチャーが当選し「買う権利」プロジェクトを導入したわけですが、ソーシャルハウジングは、事実上この政策によって抹消されてしまいましたね。

バービカン・エステートをイギリスの他のソーシャルハウジングと比較してみてください。全然違いますね。竣工時から高価なものでしたし、洗練されたデザインの意図があるのがわかるでしょう。純粋に「テッキー(技術オタク)」なブルータリズムではない。まさにレイナー・バンハムが本来の意味で用いたような意味でね。それにインターナショナルモダニズムでもない。ワッキー(へろへろ)でウォンキー(ふらふら)で、ある意味「アーツィー(芸術気取り)」だとも言える。オーナメントやデコレーションに対する野心が滲みでています。

…あなたはバービカンをただ鑑賞するだけでなく、そのモダニストのイデオロギーをご自身の感覚と経験によって探求しようとされたのですよね。つまり、数年間そこに住んでおられたわけですが...

まさに。体験してみたかったのです。私は生涯、借家人ですので不動産を持っていません。幸運なことに、短い間でしたが、これまでにも記憶に残るような住宅に住むことができました。リタイアしたら今までの思い出を振り返って、一冊の本にまとめたりするかもしれませんね。

私の考えでは、バービカン・エステートはその奇怪なデザインよりもむしろ、技術的な選択によってモダニストのイデオロギーが体現されているのだと思います。

まず第一にヒーティングシステムがありますよね。あらゆるところが床暖房になっていて、しかも電気式です。当時としては珍しい。しかもこの規模で。チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンの3人は、先進的な考えを持っていたのでしょう。暖房システムは、偏在的で、等方的で、均質的で、そして見えないものであるべきだ、と。つまり床下に。魔法のようにね!入居者の手を煩わせることなく、恒久的で快適な熱環境を提供してくれるのです。居住者は熱がどこから出てきているのか、知る必要すらありません。モダニズムの理想、つまりコントロール可能な自然がここにあるのです。どの部屋にいても完璧な気温を手に入れられる。ル・コルビュジエにとっては、全ての人が18度という温度を永遠に手にすることができる、ということを意味していました。ところが、現実は厳しいもので、システムの管理にコストがかかりすぎることが判明したのです。そこで不動産管理者は、温度を下げて15℃という「バックグラウンド」温度に設定したのですが、それでは十分に暖かくはならないのです。しかも、電気は市場から大量に安く購入され、部屋が暖められるのは深夜から朝の6時の間のみです。だから毎朝6時に起きると、サウナに入ったみたいになっているんです!日中は基本的に暖房がないでしょう。ですから、12時を超えると冬は寒くてたまらないですね。ガス管も通っていないので、暖房は電気式ストーブかスペースヒーターしかありません。危険ですし高価ですよね。床暖房は全て電気式なのですが、信じられないことに、サーモスタット(温度調整装置)を一つも設置できないんです。暑いときは窓を開けて、寒いときは電気ストーブをつける。さもなくば、このセントラルヒーティングシステムのなすがままに。このシステムはあらゆるところで作動していて、止めることができません。遠隔地で匿名の誰かが、中央集権的な手続きのもとにコントロールしているのです。慈善の精神でね。ほとんど福祉国家のメタファーのようですよ。全ての人に暖房を。揺り籠から墓場まで。委員会の同意のもとに。この議論に関しては、最近の記事で詳しく述べているので、ぜひご一読ください。(https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)

はっきり言ってバービカンの暖房システムは悪夢ですよ。ここでは、たくさん改修工事が行われていますが、金持ちな人は、部屋を買ったはいいものの、暖房調整がうまく行かないと気づいて改修するのでしょう。

私は、家は誰もが自分のニーズに合った温熱環境を選ぶことのできる場所であるべきだと思います。暑いのが好きなのか、寒いのが好きなのか、窓を開けたいのか、それとも閉めたいのか、そういったことが選択できるということです。ポストモダニズムの美学は、決して同じ二人など存在しないということを認めているのです。温熱環境の好みもそうでしょう!モダニズムは、均質性を信じていましたが、ポストモダニズムは違います。

バービカン・エステートで他に問題は感じましたか?

特にタワー型マンションで生じるような現象は問題ですね。私の住んでいたところが、まさにそうなのですが、私はそれをバーティカル・ジェントリフィケーションと呼んでいます。タワーマンションの最上階は、実業家や大金持ち、それにオリガルヒが二つや三つ部屋を買って繋げたりするでしょう。つまり最上階では、常に建築現場が動いているということです。巨大な鉄筋コンクリートの建物に住んでいるとわかりますが、30階で落としたスプーンの音は、そのまま下に降りて地下階まで響きます。業者が1日中ドリルで穴を開けたり、コンクリートを解体したり、天井を吊ったり、バスルームを作り替えたりしていることを考えてみてくださいよ。特にパンデミックの時は、みんな在宅勤務でしたから地獄でしたよ。

私の拝見した限り、バービカンのこのスパルタンスタイルは、新しい住人たちのお気に召さないのでしょう。もっと豪華で洗練された仕上げを望んでいるのです。それに、部屋の大きさは当時としては、非常に大きいのですが、時代の倹約精神からかバスルームがかなり小さく設計されていますし、現代の裕福なオーナーは好みが違いますから、バスルームも改修せざるを得ないのでしょう。

例えば、パンデミック時に私が住んでいたタワーでは、最上階に石材のカットショップのようなものが数ヶ月も設置されていました。しまいには、業者が大理石の板を上げ下げするために、三台あるエレベーターのうちの一台が占領されてしまっていました。

この「バーティカル」ジェントリフィケーションは、好みの不一致から生じているのだと思います。金持ちはこの外観が気に入らないのだと思いますし、60年代や70年代のブルータリズムにも興味がないのだと思います。比較するのもおかしいのですが、たぶんソーシャルハウジングを連想させてしまうのでしょうね。それでも彼らは、ゾラがエッフェル塔について述べたように、このバービカンのタワーについてもこう述べるのです。その姿を見たくないのであれば、その頂上にいればいいのだ、と。平面的には、それぞれの部屋は二面、あるいは三面に眺望をもっています。それに、最近までロンドンで最も背の高い41階建てのマンションでした。上からの眺めは素晴らしいですよ。人々は眺望を買うのです。そうして部屋のあらゆるところは作り替えられ、階下の全ての住人の生活は悪夢へと変わってしまうのです。

騒音に対する苦情は、特にタワー棟の方でひどいのですが、水平ブロックの棟では、それほどでもないようですね。不動産の圧力もそれほど強くないのでしょう。こちらは狭くて安いですし、上からの眺望は手に入りません。オリガルヒは、まさにこういった「中流階級」向けに見えるソーシャルハウジングなんて買いません。いや、実際そうなんですけどね。

何かポジティブな経験は得られましたか?特に素晴らしいと感じられたことなどはありますか?

騒音や隣人など、住人のことについては、お話してきましたね。建築家としては、デザインに囲まれているということは、常に良いことだと思います。チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンのデザインが、私の好みだというわけではありませんが。それに当時の彼らは、野心をカバーする技術や手段を持ち合わせていなかったように感じます。そういった欠点を差し置いても、朝起きて身の回りがデザインにあふれているのは良いことです。

それが好きな建築家のものでなくともね。そこにヴィジョンがあればいいのです。あなたがデザイナーであったり、デザイン的な知性を気にするような人であるのなら、それだけで人生は豊かになりますよね。

バービカンでは、建築家によるコンクリートのテクトニクスが目を惹きます。明らかにポール・ルドルフの精神を受け継いでいますね。私は、ポール・ルドルフのデザインを特に評価しているわけではありませんが、彼が偉大なデザイナーであることは確かです。イエール大学の建築学部で教えていたことがあるのですが、ルドルフの威圧的なほどに巨大なコンクリート造の建築に、私の目は完全に魅了されてしまいました。プロポーションの素晴らしさや、そこで発揮されたクラフトマンシップに至るまで全てが素晴らしかった。この構築物は、緻密に、そして実によく作られたものであることは明らかです。しかもそれは最初から、そしてもっとも重要なことですが、建築家の頭の中にあったものなのです。天才的ですよ。先ほども言いましたが、そのヴィジョンは共有されるものでなくても良いのです。人の目と心を満足させるには、そこに一貫性と力強さがあれば十分です。

バービカン・エステートでは、どんな時に家にいてくつろぎを感じますか?通りからロビーに入る時でしょうか?それとも自分の部屋に入る時でしょうか?

ロビーは気に入っているのですが、家にいる感じはしませんでした。常に人が行き来していたので、駅で電車を待っているような感じに近いですね。見知らぬ人に囲まれたパブリックスペースのような感じでしょうか。ドアマンは常に勤務していましたし、しっかり管理してくれていました。

ですが、部屋のドアを開けて中に入ると、すぐに自分の家にいる感覚になれるのです。魔法にかけられたように!エレベーターで120メートル上まで行くことを想像してみてください。まるでアルプスの山に登っているような感覚です。眼下に広がる雲はとても近くに感じられ、雲の上に太陽が顔を出す瞬間は、息を呑むほどです。雲を眼下に、太陽の光が翼にきらめく飛行機にいるのと同じようにね!洞窟的でほとんど地面下にいるような、あの不吉にも暗いロビー、そしてエレベーターの先にそんな光景がやって来るのです。玄関のドアを開けると、陽光が降り注ぐ。喜びに溢れる瞬間です。

5年間の生活を通して、この建物についてはどれくらい把握することができましたか?

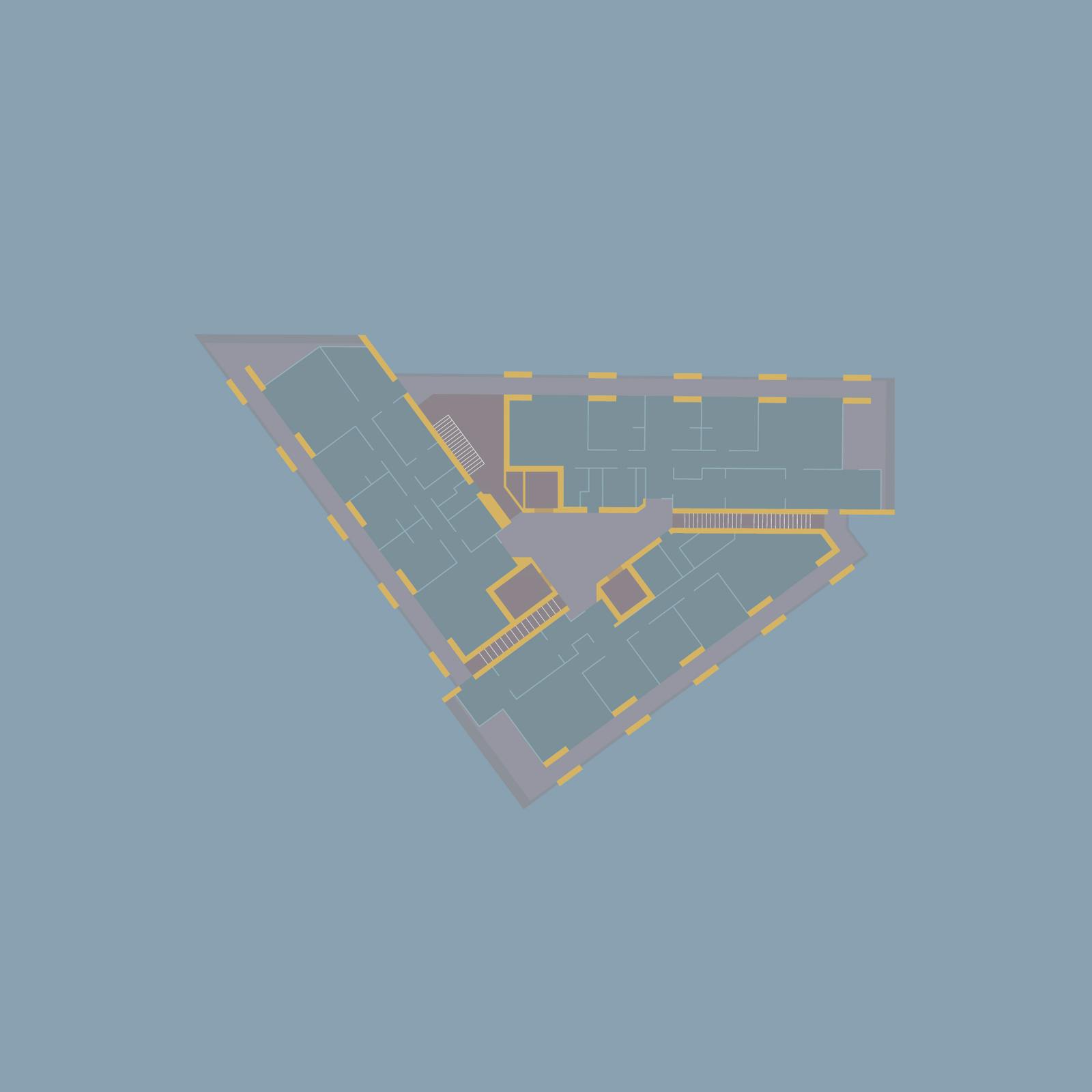

バービカンは立派な迷宮ですよ。外にでて広場を横切るたびに、誰かが訪ねてくるでしょう。「すみません。どこどこへの行き方をご存知ですか」と。誰もが永遠に迷子になっている。交通手段を分離することで、普通道路から隔離するというアイデアがそうさせているのです。ここでは空中の歩行者専用通路が用意されているのですが、それがまた非常に入り組んだ歩行者用プラットフォームなんです。プラットフォームは廊下や通路、橋やバルコニーで構成されていますが、どれも都市のスケールにはないものです。ですから、ただ従えば良いわけではなく、使い方を学んでいかないといけないのです。

チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンは、機能の分離というコルビュジエ的なモダニズムの理想を完全に取り入れようとしていたのだと思います。特に車の交通を排除するということに関してはそうですね。車はトンネルに。歩行者は橋やプラットフォームに。そうして理論的には、安全な歩行者天国ができるわけです。ところが、自転車は自転車だけ、車は車だけ、歩行者は歩行者だけといったアパルトヘイト的システムよりも、時には異なる交通手段が同じ道路を共有する方が、簡潔で快適であることに私たちはほどなくして気づくのです。こうした考え方は、少し時が経ってからポストモダニズムとともにでてくるものですね。異なる交通手段である自転車、歩行者、自動車を統合するための新しいストリートスケープをデザインしようというものです。実際このプラットフォームは、プロジェクトの中で一番最初に考えられたものでした。モダニズムは分離を目指していましたが、ポストモダニズムは統合を目指したのですね。

家の中における様々な活動の統合、それはどういったことを意味するのでしょうか?

ここ2、3年でわかってきたことですが、仕事に行くために家を出て、仕事を終えて家に戻り、それから映画や買い物に出かけるためにまた家を出る、といった考え方はもはや崩壊しているのでしょう。今こそ、私たちは、生活と仕事と余暇を同時に実現できるような場所を再発明するべきです。ちなみにそれは、産業革命以前の普通の生活様式のことでもあるのですが。

産業革命以前の時代に戻って考えてみましょう。それは、そんなに古い過去というわけではないのですが、オフィスは全てホームオフィスでしたよね。人々は家で働いていました。職人や大工、もっと言えば家具職人にシャツ職人、靴職人に帽子職人、仕立て屋さんにお針子さん... 彼らは住んでいる建物と同じ建物の中に、小さな店を構えていました。違う階に店を構えることもありました。鉄道が発明され、働きに出るという考えができる前は、そうやって生活していたのです。こうした先入観は、パンデミックで本当に変わりましたね。職人や大工、家具職人に加えて、保険ブローカーや医者、教師といったホワイトカラーの人たちも家で働くようになりました。そうして、誰が本当に「働きに出る」必要があり、誰が「家でも仕事ができる」のかがわかるようになりました。

もちろん、心理的な影響も無視できません。社会的存在としての私たちにとって、外出し人と会うことの必要性は、より理解され重要なこととして捉えられています。今日の新しいIT技術は、私たちが過去から受け継いできた近接性という概念や、コミュニティにおける「自然な」モデルというものを調査し、そこに挑戦していくことになるでしょう。

ところが、今日の市場原理は、より大きなオフィスを作り続けています。世界中の権力が、新しい地下鉄やオフィスビルの建設に投資し続けていますし、システムとして、それが都市に収益性をもたらす最も簡単な方法だと信じられているのです。

1922年には、オフィスビルを建てることは良いアイデアでした。データが集中的に管理されていた時代です。ところが今は2023年です。コンピューターのサーバーだけが集中的に管理されていて、データ管理の全ては遠隔地にあり、分散化されています。(つまり、たいていのオフィスワークはどこでもできるということです。)

人々が必要とするような家が建てられていない、ということですね。逆説的なことですね。

バービカン・エステートは、1956年に考案されました。人々が朝8時に家を出て仕事に行くという時代です。そして午後6時には家に帰ってくる。今でもそうしている人はいますが、だんだん減ってくるでしょうね。今こそ何か違うものが発明されるべきなのです。私たちが暮らし、働き、売り買いし、余暇を楽しむための新しい空間と新しい技術的インフラが必要とされているのです。それも、物理的な人的移動を最小限にし、人、材料、食料、商品などの機械的な輸送も削減できるような方法で。バービカンは、カーボンフットプリントのモニュメントなんですよ。だからこそ改修するのも難しいのでしょう。時が解決してくれるのかもしれませんが...

2022年9月15日

Mario Carpo: It’s an idea of the fifties, built in the sixties, that came to market in the seventies. The high rises of the Barbican estate were inaugurated only a few months before Charles Jencks published „The language of postmodern architecture”. That was the tipping point. Before 1977, the Barbican was the future. In 1977 the Barbican became the past.

IT IS A HOUSING COMPLEX THAT CAN BE LOVED AND HATED AT THE SAME TIME.

The spirit of modernism—the Frankenstein-like monster of post-war society’s techno-social imagination—was a strong proponent of the idea that individual housing should not exist. Instead, mass-produced and prefabricated apartments should serve as a template for standardised living. It was not only a pragmatic response to the conditions of a big city, pushing to build densely. It was an ideology of mass-production and economy of scale, addressed to modern men and women, supposed to be themselves standard products.

The Barbican Estate was the result of this modernist ideology: its vast scale, repetition, exposed concrete, and central heating system expressed clearly the credo of the fifties. Even though it was a relatively expensive complex addressed to the upper middle class, aesthetically and atmospherically it did not fit to its time. Starting from the late 1970s, its design was seen as the materialisation of a previous generation’s dreams.

Today, many perceive it to be a plain structure of 2000 affordable homes, they photograph, and study it as such, but nothing could be further from the truth. It is not and never was a social housing complex.

WHAT IS THE SOURCE OF THE MISCONCEPTION?

People think that brutalism was the style of social housing because social housing was built in concrete, which is why the Barbican is so popular among my students. But it’s only a nostalgia for the time when the state actually built social housing. But then, in 1979, Margaret Thatcher was elected and ushered in her ‘Right to Buy’ project - a policy that effectively eliminated social housing.

If you compare the Barbican Estate with other British social housing, evidently it was never meant to be one. It was more expensive from the start, and it had a more sophisticated design intention. It was not pure “techy” brutalism, so to speak, in Renyer Banham’s original sense of the term; and it was no longer international modernism. It is wacky and wonky; “artsy” in a sense. There was an ambition of ornamentation, decoration, it expressed a character.

…AND YOU WANTED TO GO BEYOND MERE OBSERVATION AND EXPLORE THE MODERNIST IDEOLOGY WITH YOUR SENSES AND EXPERIENCES, BY LIVING THERE FOR A FEW YEARS…

Yes, I wanted to try it. I am a tenant for life, so to speak--I don’t own real estate--and I have been fortunate enough to live, briefly, in some memorable residences. When I retire and look back on all my memories, I may put them all in a book.

As far as I am concerned, the Barbican Estate embodies the modernist ideology through its technical choices, rather than in its often-peculiar design.

The heating system, for a start. There is underfloor heating everywhere--and electric to boot, an unusual choice at the time, and at that scale. Chamberlain, Powell and Bon had this forward-thinking notion that heating should be ubiquitous, isotropic, homogenous, and invisible - underfloor - like magic! It would ensure permanent thermal comfort without any intervention from the tenants, without the residents even ever knowing where the heat came from. This was an ideal of modernism: a controllable nature. Enter any apartment and you’d always find a perfect temperature--which for Le Corbusier was meant to be 18 Celsius for all and forever. But then reality hit them hard; managing this type of system proved to be too costly, so estate management opted for a lower “background” temperature of 15 C instead – which isn’t warm enough. Moreover, the estate purchases electricity in bulk on the energy market when prices are low, and they heat their apartments from midnight to 6 a.m. This means that you wake up every day at 6 a.m., stepping into what feels like a sauna! And there is basically no heating during the day, so after 12 a.m. it starts to be too cold in winter. There are no gas pipes anywhere at the Barbican, therefore the only way to heat your apartment is an electric stove or space heater—dangerous and expensive. This seems hard to believe, but, although all underfloor heating in the estate is electric, there is no way to install a single thermostat--anywhere. You may open the windows when it’s too hot, and turn your electric stove on when it’s too cold, but otherwise you are left at the mercy of a ubiquitous, unstoppable system of centralised heating which is controlled by a remote, anonymous, centralised bureaucracy, ideally benevolent: almost a metaphor of the welfare state, where even heating is planned for all, from cradle to grave: heating by consensus and by committee. I discussed this argument at length in a recent article; you may read it here (https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)

To put it bluntly, the heating in the Barbican is a nightmare and that is one of the reasons why so much retrofitting has to be done when wealthy people buy these apartments and realise that it is not possible to adjust the heating.

In my opinion, a house should be a place where anyone can choose the thermal environment that best suits their needs. Whether you prefer it hot or cold, open windows or closed; the beauty of postmodernism is recognising that no two people are alike - and neither are their temperature preferences! Modernism believed in homogeneity; postmodernism didn’t.

WHAT ARE THE OTHER PROBLEMS OF THE BARBICAN ESTATE?

There is a phenomenon, a problem occurring particularly in the towers, which is incidentally where I lived, which I would call vertical gentrification. At the top of the high rises the tycoons, the billionaires, the oligarchs buy apartments, and combine two or three of them together. In practice, it leads to a permanent building site on the top floors. If you live in a building made of massive, reinforced concrete, you hear a spoon dropped on the 30th floor all the way down to the basement. Given that, think of builders drilling all day long, demolishing reinforced concrete or hanging suspended ceilings, remaking bathrooms. During the pandemic in particular, when we were all working from home, it was hell.

From what I have seen, the new prosperous residents of the Barbican are not pleased with its spartan style, wanting instead more luxurious and polished finishes. What’s more, even though the apartments were considered quite large in their time, they were planned with tiny bathrooms, likely due to the era’s spirit of frugality. Today’s affluent owners have different tastes; so bathrooms are being retrofitted.

For instance, in the tower where I lived during the pandemic, there was a kind of stone cutting shop installed on the top floors, for months on end, which consequently meant that one out of the three elevators was permanently used by the builders, going up and down, delivering slabs of marble.

In my opinion, this “vertical” gentrification is a result of a discrepancy of taste. The rich probably don’t like how the building looks, and they have no interest in brutalism of the 60s and 70s--which probably reminds them of social housing, even if the parallel is unwarranted in this instance. But they say the same of the Barbican towers as Zola said of the Eiffel Tower - the only way not to see it is to be on top of it. Due to the layout of the plan, each apartment has two or three aspects. It was until recently the tallest residential building in London - 41 floors. The view from the top is stunning, so the people buy the view and remake everything, which turns the life of all the residents below into a nightmare.

The complaints about noise, which is extreme in the high rises, seem to be manageable in the horizontal blocks, because the pressure of real estate there is not as strong. If you’re looking for a view from the top, you don’t have it. The apartments are smaller, cheaper. The oligarchs don’t buy the flats that really look like “middle class” social housing--which they were.

WHAT WERE YOUR POSITIVE EXPERIENCES? IS THERE SOMETHING THAT YOU FOUND FANTASTIC?

I told you the experience of a resident, noise, neighbours, etc. But, as an architect it is always good to be surrounded by design. I don’t always like the choices of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. At times it seems to me that they didn’t have the technology and the means to sustain their ambitions. However, in spite of these shortcomings, it is good to see a design intention all around you, when you wake up in the morning.

It doesn’t have to be the intention of an architect you like; it just needs to be driven by a vision. If you are a designer, or if you simply care about design intelligence, it is something that makes your life better.

In Barbican, the architects’ concrete tectonics are remarkable, very much in the spirit of Paul Rudolph. Even though I don’t particularly appreciate Paul Rudolph’s designs, it’s evident he was a great designer. When I taught at the Yale School of Architecture - an intimidatingly large concrete building by Rudolph - everything about it captivated my eyes, from its proportions to its craftsmanship. It’s clear that this structure has been carefully and skillfully built, first and foremost, in the mind of an architect--and an architect of genius. As I said, it doesn’t have to be a vision you share; its consistency and strength is enough to please one’s eyes and mind.

WHEN DO YOU FEEL AT HOME IN THE BARBICAN? IS IT WHEN YOU STEP OFF THE STREET AND INTO THE LOBBY, OR LATER WHEN YOU ARRIVE TO AND ENTER YOUR OWN APARTMENT?

Although I liked the lobby, it certainly didn’t feel like home. It felt more like waiting for a train at the station with people constantly coming and going. plus, there’s still that feeling of being in a public space surrounded by strangers. The doorman was always on duty, vigilantly keeping watch over the area.

But when you open your door and step inside, there’s a feeling of being right at home. It almost feels like magic! Imagine the experience of taking an elevator 120 meters up – it’s just as if you were climbing a mountain in the Alps. The clouds below feel so close that when they part to reveal the sun above, it is breathtaking - similar to being on an aeroplane with clouds beneath and sunshine reflecting off its wings!

All this comes after leaving the cavernous and almost chthonian, sinister darkness of the lobbies and elevators behind you; pushing through your front door leads into full sunlight. That was a pleasure.

AFTER FIVE YEARS OF LIVING THERE, HOW WELL DO YOU KNOW THE WHOLE COMPLEX?

The Barbican is famously labyrinthine. Every time you go out and cross the public plaza, someone will ask you: „excuse me, do you know how to get to…” Everyone is permanently lost. It is the result of the idea of a separation of traffics and the segregation of normal streets--which are replaced here by aerial pedestrian walkways. Meaning, there is the very intricate pedestrian platform, made of corridors, passageways, bridges, and balconies that are not at the scale of the city and must be learnt and not followed.

Chamberlain, Powell and Bon fully embraced the Corbusian modernist ideals of separating functions, and in particular, removing traffic. Cars are in tunnels and pedestrians are on bridges and platforms; in theory, a safe pedestrian paradise. Shortly thereafter we realised that sometimes it is easier and more pleasant to share the road with different traffics, rather than having an apartheid system whereby bicycles only meet bicycles, cars only cars and pedestrians, only other pedestrians. But this came a little later, with postmodernism: the idea to design a new streetscape meant to integrate different traffics: bicycles, pedestrian and cars. The platform is the element that dates the project the most. Modernism was about segregation; postmodernism has been about integration.

WHAT ABOUT INTEGRATION OF DIVERSE ACTIVITIES IN A HOUSE?

What we have learnt in the last two or three years is that the idea that you leave home to go to work and you come back home after you have been working and then you leave home, again, to go out to the movies, or go shopping, or whatever, has fallen apart. Now we need to reinvent a place where we can live and work and have fun at the same time, which by the way was the normal way of living before the industrial revolution.

Back then--in the pre-industrial age, which was not long ago--every office was a home office. People worked at home - artisans, carpenters, cabinet makers; shirtmakers, shoemakers, hatmakers, tailors, seamstresses... They had a little shop in the same building where they lived, sometimes on different floors. That’s the way they lived before we invented the railway and we decided that we needed to go and work in a different place. This preconceived idea has been truly challenged during the pandemic, when artisans, carpenters, cabinet makers were joined by white collar workers--insurance brokers, doctors, teachers. It showed who really needed to “go to work” and who could “work from home”.

Of course, we shouldn’t neglect the psychological effects, which are becoming more understood and consequential, the need and meaning for us as social beings, to go out, to meet other people. Today’s new IT (information technology) will inevitably probe and challenge the supposedly “natural” models of community and proximity we have inherited from the past.

Yet, today, market forces keep building bigger and bigger offices, authorities around the world are still investing in building new metro and subway lines and new office buildings, the system remains convinced that it is the easiest way to make cities profitable. It was perhaps a good idea to build office buildings in 1922, when data was centralised; now in 2023, only the computer server is centralised, all data management can be remote and despatialised (i.e., most office work can happen anywhere).

NOBODY IS BUILDING THE HOUSES PEOPLE NEED. THAT’S THE PARADOX.

The Barbican was conceived in 1956 when people left home at 8 a.m. to go to work. They came back home at 6 p.m. and some people will still do that, but fewer and fewer people will. It’s time to invent something different. We need new spaces, and new technical infrastructure’s that will allow people to live, work, shop and have fun with minimal physical displacement, and minimising the need for the mechanical transportation of people, raw materials, food, and goods. The Barbican, which is a monument to carbon footprint, may not be easy to retrofit for that purpose. Time will tell...

15.09.2022

马里奥-卡波: 这是一个50年代的想法,在60年代建造,在70年代进入市场。巴比肯住宅区的高层建筑在查尔斯-詹克斯(Charles Jencks)发表 《后现代建筑的语言》前几个月才开始启用。那是一个转折点。在1977年之前,巴比肯是未来。1977年,巴比肯成为了过去。

它是一个让人可以既爱又恨的住宅综合体。

现代主义的精神——战后社会的技术社会想象中弗兰肯斯坦般的怪物——坚定地支持独立住宅不应存在的观念。相反,大规模生产和预制的公寓应该作为标准化生活的模板。这不仅是对大城市条件的务实回应,推动了建筑的密集化。这是一种大规模生产和规模经济的意识形态,针对的是现代男女,他们被假定为标准化的产品。

巴比肯屋村是这种现代主义意识形态的结果:其巨大的规模、重复、裸露的混凝土和中央供暖系统明确表达了50年代的信条。尽管它是一个相对昂贵的建筑群,针对中上层阶级,但从美学和氛围上来说,它并不适合于它的时代。从70年代末开始,它的设计被视为上一代人梦想的具体化。

今天,许多人认为它是一个由2000套经济适用房组成的普通构筑物,他们拍摄并研究它,但实际情况与此相去甚远。它从未是一个社会住房综合体,也永远不是。

这种误解的根源是什么?

人们认为粗野主义是社会住房的风格,因为社会住房是用混凝土建造的,这就是为什么巴比肯在我的学生中如此受欢迎。但这只是对国家实际上建造社会住房时代的怀旧。但后来在1979年,玛格丽特-撒切尔当选,并迎来了她的 "购买权 "项目——这项政策实际上消除了社会住房。

如果你将巴比肯屋村与其他英国社会住房进行比较,显然它从来就不是为了成为一个社会住房。它从一开始就更为昂贵,而且具有更复杂的设计意图。它不是纯粹的 "技术性 "粗野主义,可以说是雷尼尔-班纳姆最初意义上的粗野主义;它也不再是国际现代主义。 它是古怪的,不稳定的;在某种意义上是 "艺术的"。它具有修饰,装饰的野心,它表达了一种性格。

...而你想超越单纯的观察,用你的感官和经验来探索现代主义的意识形态,在那里生活几年...

是的,我想试试。我是个终身租户,可以这么说——我不拥有房地产——我有幸在一些令人难忘的住所中短暂的居住过。当我退休并回顾我所有的记忆时,我可能会把它们都写进一本书。

在我看来,巴比肯屋村通过其技术选择,而不是其通常特别的设计,体现了现代主义的思想。

首先是供暖系统。 巴比肯住宅区使用的是通铺的电地暖,这在当时以及那样的规模下是一种不寻常的选择。张伯伦、鲍威尔和本恩公司有一个具有前瞻性的概念,即供暖应该是无处不在的、各向同性的、均匀的和无形的——地板下的——就像魔术一样!这将确保恒温舒适,而不需要在地面上留下痕迹,也不需要住户的任何干预,甚至他们都不知道热量从何而来。这是现代主义的一个理想:一个可控制的自然。进入任何一间公寓,你都能感受到完美的温度——对勒-柯布西耶来说,这个温度应该是18摄氏度,永远适用于所有人。 但是,现实给了他们沉重的打击;管理这种类型的系统被证明太昂贵了,所以屋村管理部门选择了一个较低的 "背景 "温度,即15摄氏度——这并不够温暖。此外,当价格低的时候,屋村在能源市场上大量购买电力,他们从午夜到早上6点为公寓供暖。这意味着你每天早上6点醒来时,仿佛置身于桑拿房中!白天基本上没有供暖,所以午夜后的冬季会变得太冷。巴比肯屋村没有任何煤气管道,因此你只能通过使用电炉或电暖器来加热你的公寓——危险且昂贵。这似乎难以置信,但是,尽管屋村里所有的地暖都是电动的,但没有办法安装单独的温控器——在任何地方。 你可以在太热的时候打开窗户,在太冷的时候打开电炉,但除此之外,你只能任由一个无处不在、不可阻挡的集中供暖系统摆布,这个系统由一个遥远的、匿名的、集中的官僚机构控制,理想上是仁慈的:几乎是福利国家的一个隐喻,在那里,甚至供暖都是为所有人规划的,从摇篮到坟墓:通过共识和委员会供暖。 我在最近的一篇文章中详细讨论了这个论点;你可以在这里阅读(https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)。

直截了当地说,巴比肯的供暖是一场噩梦,这也是为什么当富人买下这些公寓并意识到不可能调节供暖时,必须进行如此多改造的原因之一。

在我看来,住宅应该是一个任何人都可以选择最适合自己需求的热环境的地方。无论你喜欢热的还是冷的,开窗还是关窗;后现代主义的魅力在于认识到没有两个人是相同的——他们的温度偏好也是如此! 现代主义相信同质性;后现代主义不相信。

巴比肯屋村的其他问题是什么?

有一个现象,一个特别发生在塔楼上的问题,也就是我住过的地方,我称之为垂直士绅化。在高层建筑的顶层,富豪、亿万富翁、寡头购买公寓,并将其中的两到三套组合在一起。在实践中,它导致了在顶层的永久建筑工地。如果你住在一栋由巨大的钢筋混凝土制成的大楼里,你会听到一个勺子从30楼一直掉到地下室的声音。鉴于此,想象一下建筑工人整天钻孔、拆除钢筋混凝土或悬挂吊顶、重修浴室。 特别是在疫情期间,当我们都在家里工作时,那真是地狱。

据我所见,巴比肯繁荣的新居民并不满意其简陋的风格,而是想要更豪华和精致的装饰。更重要的是,尽管这些公寓在当时被认为是相当大的,但浴室被规划的很小,可能是由于那个时代的节俭精神。如今的富裕业主有着不同的品味;因此,浴室正在被改造。

例如,在疫情期间我居住的塔楼里,顶层安装了一个石材切割车间,持续了数月,这就意味着三部电梯中的一部被建筑承包商长期使用,上上下下,运送大理石板。

在我看来,这种 "垂直 "的士绅化是一种品味差异的结果。有钱人可能不喜欢这个建筑的外观,他们对60年代和70年代的粗野主义没有兴趣——这会让他们想起了社会住房,即使在这个例子中这种类比是没有必要的。 但他们对巴比肯塔楼的评价和左拉对埃菲尔铁塔的评价一样——不看它的唯一方法就是站在它的上面。由于平面布局,每个公寓都有两个或三个朝向。直到最近,它还是伦敦最高的住宅楼——41层。从顶部看去,景色令人惊叹,因此人们购买了视野并改造了一切,这让下面所有居民的生活变成了一场噩梦。

关于噪音的投诉,在高层建筑中是很极端的,而在水平向的街区中似乎是可以控制的,因为那里的房地产压力没有那么大。如果你想从顶层看风景,那是无法实现的。公寓更小更便宜。寡头们不会购买那些真的看起来像 "中产阶级 "社会住房的公寓——因为它们曾经确实如此。

你的积极经验是什么?有什么是你觉得不可思议的吗?

我告诉你一个居民的经验,噪音,邻居,等等。但是,作为一个建筑师,被设计所包围总是好的。我并不总是喜欢张伯伦、鲍威尔和本恩公司的选择。有时候我觉得他们没有技术和手段来支持他们的抱负。然而,尽管存在这些缺点,早上醒来时看到周围都是设计意图还是很好的。

这个意图不一定是你喜欢的建筑师的意图,它只需要由一个愿景驱动。如果你是一个设计师,或者你只是关心设计的智慧,它会让你的生活变得更美好。

在巴比肯,建筑师们的混凝土构造是非常了不起的,非常符合保罗-鲁道夫的精神。尽管我并不特别欣赏保罗-鲁道夫的设计,但很明显他是一个伟大的设计师。当我在耶鲁大学建筑学院教书时——那座鲁道夫设计的令人生畏的大型混凝土建筑——从比例到工艺,它的一切都吸引着我的眼睛。很明显,这个结构首先是在一位建筑师的头脑中精心而熟练地建造的——而且是一位天才的建筑师。 正如我所说的,它不一定是你的共同愿景;它的一致性和力量足以让人眼前一亮,心生赞叹。

在巴比肯,你什么时候有家的感觉?是在你离开街道进入大堂的时候,还是在你到达并进入自己的公寓后?

虽然我喜欢那个大堂,但它肯定没有家的感觉。它更像是在车站等火车,人们不断地进进出出。另外,还有那种置身于公共空间被陌生人包围的感觉。门卫总是在值班,警惕地看守着这个区域。

但当你打开自家的门,踏进去的时候,有一种立刻到家的感觉。这几乎是一种神奇的感觉! 想象一下乘坐电梯上升120米的体验——就像你在阿尔卑斯山上爬山一样。下面的云层感觉如此之近,以至于当它们分开,露出上面的太阳时,令人叹为观止——类似于在飞机上,云层在下面,阳光从机翼上反射出来!

所有这一切都发生在你离开了洞穴般阴暗险恶的大堂和电梯的时刻之后;推开你的前门走进充满阳光的屋内。这是一种愉悦的感觉。

在那里生活了五年之后,你对整个建筑群的了解程度如何?

巴比肯屋村是因其迷宫般的布局而闻名。每次你出门,穿过公共广场,都会有人问你: "对不起,你知道怎么去..." 每个人都会永远的在迷路。这是交通分离和隔离正常街道想法的结果,街道在这里被空中人行道所取代。意思是说,这里有非常复杂的人行平台,由走廊、通道、桥梁和阳台组成,它们不符合城市的尺度,必须学习而不是遵循。

张伯伦、鲍威尔和本恩完全接受了柯布西耶式的现代主义理想,即分离功能,特别是消除交通。汽车在隧道里,行人在桥梁和平台上;理论上,这是一个安全的行人天堂。此后不久,我们意识到,有时与不同的交通方式共享道路会更容易、更令人愉快,而不是有一个隔离制度,即自行车只能遇到自行车,汽车只能遇到汽车,行人只能遇到其他行人。但这是后来才有的,是后现代主义:旨在设计一个新的街景,整合不同的交通方式:自行车、行人和汽车。平台是该项目最具时代特征的元素。现代主义是关于隔离的;后现代主义是关于整合的。

那么,在一个住宅里不同活动的整合呢?

在过去的两三年里,我们学到的是,你离开家去工作,工作后回到家,然后再次离开家,去看电影,或去购物,或其他,这种想法已经崩溃了。现在,我们需要重新创造一个我们可以同时生活、工作并享受乐趣的地方,顺便说一下,这是工业革命之前正常的生活方式。

那时——在前工业时代,也就是不久前——每个办公室都是家庭办公。人们在家里工作——工匠、木匠、橱柜制造商;衬衫制造商、鞋匠、帽子制造商、裁缝、女裁缝...... 他们在自己居住的同一栋楼里有一个小店,有时在不同的楼层。这就是他们在我们发明铁路之前的生活方式,我们决定我们需要去不同的地方工作。这种先入为主的想法在疫情期间受到了真正的挑战,这时白领工人——保险经纪人、医生、教师加入了工匠、木匠、橱柜制造商。这表明谁真正需要 "去工作",谁可以 "在家里工作"。

当然,我们不应该忽视心理上的影响,这些影响正变得越来越被人理解和重视,我们作为社会人,走出去,认识其他人的需求和意义。 今天的新IT(信息技术)将不可避免地探索和挑战我们从过去继承下来的所谓 "自然 "的社区和接近模式。

然而,今天,市场力量不断地建造越来越大的办公室,世界各地的当局仍然在投资建设新的地铁线路和办公楼,系统仍坚信这是使城市盈利的最简单的方式。

在1922年,建造办公楼也许是个好主意,当时数据是集中的;现在到了2023年,只有计算机服务器是集中的,所有的数据管理都可以是远程和去空间化的(也就是说,大多数办公室工作可以在任何地方进行)。

没有人在建造人们需要的住宅。这就是矛盾之处。

巴比肯屋村是在1956年构思的,当时人们早上8点离开家去工作,下午6点回家,有些人仍然会这样做,但越来越少的人会如此。现在是发明一些不同的东西的时候了。我们需要新的空间和新的技术基础设施,让人们在生活、工作、购物和娱乐的同时,尽量减少物理位移,并尽量减少对人员、原材料、食品和货物的机械运输的需求。 巴比肯屋村是一个碳足迹的纪念碑,可能不容易进行改建以适应这一目的。 时间会告诉我们...

2022年9月15日

マリオ・カルポ: アイデアは50年代のものですが、建てられたのは60年代のことです。そして市場に出回ったのは70年代のことです。バービカン・エステートが竣工したのは、チャールズ・ジェンクスが『ポスト・モダニズムの建築言語』を発表したほんの数ヶ月前のことですから、ちょうど転換期だったのでしょう。1977年以前には、バービカンは未来にあり、1977年には過去のものとなってしまった。

バービカンは愛されていましたが、同時に憎まれてもいた、と。

モダニズムの精神。戦後技術社会の想像力が生み出したフランケンシュタイン的怪物。それは、個人住宅など存在すべきではないと強く提唱していました。その代わりに、大量生産されたプレファブの集合住宅が、標準的生活のテンプレートとして機能するはずである、と。それは、高密化する大都市の現状への単なる現実的な対応にとどまるものではありませんでした。マスプロダクションやスケールメリットのイデオロギーとして、近代的男性、そして女性へと差し向けられたものでした。それ自体が標準的なプロダクトとしてね。

バービカン・エステートは、モダニストのイデオロギーの成果なのです。その広大なスケール、反復、剥き出しのコンクリート、そしてセントラルヒーティング。50年代的な信条が明確に表現されています。比較的高価な集合住宅として、上位中産階級をターゲットにしていましたが、美的にも雰囲気的にも時代に沿ったものではなかったのです。それが、昔の世代の夢の具現化として認識され始めたのは、1970年代の後半からです。

今では多くの人が、2000戸の「手頃なおうち」の並んだ平凡な建物だと思っていますし、そうやって撮影したり、研究したりしています。でもね、見当違いなんです。ソーシャルハウジングの類いでは全くないのですから。

なぜ、そのように理解されてしまっているのでしょうか?

ブルータリズムのことを、ソーシャルハウジングのスタイルだと勘違いしているのでしょう。コンクリートで建てられていますから。だからバービカン・エステートは学生にも人気がある。ただそれも、国が本当にソーシャルハウジングを建設していた時代へのノスタルジーに過ぎないのだと思います。1979年にマーガレット・サッチャーが当選し「買う権利」プロジェクトを導入したわけですが、ソーシャルハウジングは、事実上この政策によって抹消されてしまいましたね。

バービカン・エステートをイギリスの他のソーシャルハウジングと比較してみてください。全然違いますね。竣工時から高価なものでしたし、洗練されたデザインの意図があるのがわかるでしょう。純粋に「テッキー(技術オタク)」なブルータリズムではない。まさにレイナー・バンハムが本来の意味で用いたような意味でね。それにインターナショナルモダニズムでもない。ワッキー(へろへろ)でウォンキー(ふらふら)で、ある意味「アーツィー(芸術気取り)」だとも言える。オーナメントやデコレーションに対する野心が滲みでています。

…あなたはバービカンをただ鑑賞するだけでなく、そのモダニストのイデオロギーをご自身の感覚と経験によって探求しようとされたのですよね。つまり、数年間そこに住んでおられたわけですが...

まさに。体験してみたかったのです。私は生涯、借家人ですので不動産を持っていません。幸運なことに、短い間でしたが、これまでにも記憶に残るような住宅に住むことができました。リタイアしたら今までの思い出を振り返って、一冊の本にまとめたりするかもしれませんね。

私の考えでは、バービカン・エステートはその奇怪なデザインよりもむしろ、技術的な選択によってモダニストのイデオロギーが体現されているのだと思います。

まず第一にヒーティングシステムがありますよね。あらゆるところが床暖房になっていて、しかも電気式です。当時としては珍しい。しかもこの規模で。チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンの3人は、先進的な考えを持っていたのでしょう。暖房システムは、偏在的で、等方的で、均質的で、そして見えないものであるべきだ、と。つまり床下に。魔法のようにね!入居者の手を煩わせることなく、恒久的で快適な熱環境を提供してくれるのです。居住者は熱がどこから出てきているのか、知る必要すらありません。モダニズムの理想、つまりコントロール可能な自然がここにあるのです。どの部屋にいても完璧な気温を手に入れられる。ル・コルビュジエにとっては、全ての人が18度という温度を永遠に手にすることができる、ということを意味していました。ところが、現実は厳しいもので、システムの管理にコストがかかりすぎることが判明したのです。そこで不動産管理者は、温度を下げて15℃という「バックグラウンド」温度に設定したのですが、それでは十分に暖かくはならないのです。しかも、電気は市場から大量に安く購入され、部屋が暖められるのは深夜から朝の6時の間のみです。だから毎朝6時に起きると、サウナに入ったみたいになっているんです!日中は基本的に暖房がないでしょう。ですから、12時を超えると冬は寒くてたまらないですね。ガス管も通っていないので、暖房は電気式ストーブかスペースヒーターしかありません。危険ですし高価ですよね。床暖房は全て電気式なのですが、信じられないことに、サーモスタット(温度調整装置)を一つも設置できないんです。暑いときは窓を開けて、寒いときは電気ストーブをつける。さもなくば、このセントラルヒーティングシステムのなすがままに。このシステムはあらゆるところで作動していて、止めることができません。遠隔地で匿名の誰かが、中央集権的な手続きのもとにコントロールしているのです。慈善の精神でね。ほとんど福祉国家のメタファーのようですよ。全ての人に暖房を。揺り籠から墓場まで。委員会の同意のもとに。この議論に関しては、最近の記事で詳しく述べているので、ぜひご一読ください。(https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)

はっきり言ってバービカンの暖房システムは悪夢ですよ。ここでは、たくさん改修工事が行われていますが、金持ちな人は、部屋を買ったはいいものの、暖房調整がうまく行かないと気づいて改修するのでしょう。

私は、家は誰もが自分のニーズに合った温熱環境を選ぶことのできる場所であるべきだと思います。暑いのが好きなのか、寒いのが好きなのか、窓を開けたいのか、それとも閉めたいのか、そういったことが選択できるということです。ポストモダニズムの美学は、決して同じ二人など存在しないということを認めているのです。温熱環境の好みもそうでしょう!モダニズムは、均質性を信じていましたが、ポストモダニズムは違います。

バービカン・エステートで他に問題は感じましたか?

特にタワー型マンションで生じるような現象は問題ですね。私の住んでいたところが、まさにそうなのですが、私はそれをバーティカル・ジェントリフィケーションと呼んでいます。タワーマンションの最上階は、実業家や大金持ち、それにオリガルヒが二つや三つ部屋を買って繋げたりするでしょう。つまり最上階では、常に建築現場が動いているということです。巨大な鉄筋コンクリートの建物に住んでいるとわかりますが、30階で落としたスプーンの音は、そのまま下に降りて地下階まで響きます。業者が1日中ドリルで穴を開けたり、コンクリートを解体したり、天井を吊ったり、バスルームを作り替えたりしていることを考えてみてくださいよ。特にパンデミックの時は、みんな在宅勤務でしたから地獄でしたよ。

私の拝見した限り、バービカンのこのスパルタンスタイルは、新しい住人たちのお気に召さないのでしょう。もっと豪華で洗練された仕上げを望んでいるのです。それに、部屋の大きさは当時としては、非常に大きいのですが、時代の倹約精神からかバスルームがかなり小さく設計されていますし、現代の裕福なオーナーは好みが違いますから、バスルームも改修せざるを得ないのでしょう。

例えば、パンデミック時に私が住んでいたタワーでは、最上階に石材のカットショップのようなものが数ヶ月も設置されていました。しまいには、業者が大理石の板を上げ下げするために、三台あるエレベーターのうちの一台が占領されてしまっていました。

この「バーティカル」ジェントリフィケーションは、好みの不一致から生じているのだと思います。金持ちはこの外観が気に入らないのだと思いますし、60年代や70年代のブルータリズムにも興味がないのだと思います。比較するのもおかしいのですが、たぶんソーシャルハウジングを連想させてしまうのでしょうね。それでも彼らは、ゾラがエッフェル塔について述べたように、このバービカンのタワーについてもこう述べるのです。その姿を見たくないのであれば、その頂上にいればいいのだ、と。平面的には、それぞれの部屋は二面、あるいは三面に眺望をもっています。それに、最近までロンドンで最も背の高い41階建てのマンションでした。上からの眺めは素晴らしいですよ。人々は眺望を買うのです。そうして部屋のあらゆるところは作り替えられ、階下の全ての住人の生活は悪夢へと変わってしまうのです。

騒音に対する苦情は、特にタワー棟の方でひどいのですが、水平ブロックの棟では、それほどでもないようですね。不動産の圧力もそれほど強くないのでしょう。こちらは狭くて安いですし、上からの眺望は手に入りません。オリガルヒは、まさにこういった「中流階級」向けに見えるソーシャルハウジングなんて買いません。いや、実際そうなんですけどね。

何かポジティブな経験は得られましたか?特に素晴らしいと感じられたことなどはありますか?

騒音や隣人など、住人のことについては、お話してきましたね。建築家としては、デザインに囲まれているということは、常に良いことだと思います。チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンのデザインが、私の好みだというわけではありませんが。それに当時の彼らは、野心をカバーする技術や手段を持ち合わせていなかったように感じます。そういった欠点を差し置いても、朝起きて身の回りがデザインにあふれているのは良いことです。

それが好きな建築家のものでなくともね。そこにヴィジョンがあればいいのです。あなたがデザイナーであったり、デザイン的な知性を気にするような人であるのなら、それだけで人生は豊かになりますよね。

バービカンでは、建築家によるコンクリートのテクトニクスが目を惹きます。明らかにポール・ルドルフの精神を受け継いでいますね。私は、ポール・ルドルフのデザインを特に評価しているわけではありませんが、彼が偉大なデザイナーであることは確かです。イエール大学の建築学部で教えていたことがあるのですが、ルドルフの威圧的なほどに巨大なコンクリート造の建築に、私の目は完全に魅了されてしまいました。プロポーションの素晴らしさや、そこで発揮されたクラフトマンシップに至るまで全てが素晴らしかった。この構築物は、緻密に、そして実によく作られたものであることは明らかです。しかもそれは最初から、そしてもっとも重要なことですが、建築家の頭の中にあったものなのです。天才的ですよ。先ほども言いましたが、そのヴィジョンは共有されるものでなくても良いのです。人の目と心を満足させるには、そこに一貫性と力強さがあれば十分です。

バービカン・エステートでは、どんな時に家にいてくつろぎを感じますか?通りからロビーに入る時でしょうか?それとも自分の部屋に入る時でしょうか?

ロビーは気に入っているのですが、家にいる感じはしませんでした。常に人が行き来していたので、駅で電車を待っているような感じに近いですね。見知らぬ人に囲まれたパブリックスペースのような感じでしょうか。ドアマンは常に勤務していましたし、しっかり管理してくれていました。

ですが、部屋のドアを開けて中に入ると、すぐに自分の家にいる感覚になれるのです。魔法にかけられたように!エレベーターで120メートル上まで行くことを想像してみてください。まるでアルプスの山に登っているような感覚です。眼下に広がる雲はとても近くに感じられ、雲の上に太陽が顔を出す瞬間は、息を呑むほどです。雲を眼下に、太陽の光が翼にきらめく飛行機にいるのと同じようにね!洞窟的でほとんど地面下にいるような、あの不吉にも暗いロビー、そしてエレベーターの先にそんな光景がやって来るのです。玄関のドアを開けると、陽光が降り注ぐ。喜びに溢れる瞬間です。

5年間の生活を通して、この建物についてはどれくらい把握することができましたか?

バービカンは立派な迷宮ですよ。外にでて広場を横切るたびに、誰かが訪ねてくるでしょう。「すみません。どこどこへの行き方をご存知ですか」と。誰もが永遠に迷子になっている。交通手段を分離することで、普通道路から隔離するというアイデアがそうさせているのです。ここでは空中の歩行者専用通路が用意されているのですが、それがまた非常に入り組んだ歩行者用プラットフォームなんです。プラットフォームは廊下や通路、橋やバルコニーで構成されていますが、どれも都市のスケールにはないものです。ですから、ただ従えば良いわけではなく、使い方を学んでいかないといけないのです。

チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンは、機能の分離というコルビュジエ的なモダニズムの理想を完全に取り入れようとしていたのだと思います。特に車の交通を排除するということに関してはそうですね。車はトンネルに。歩行者は橋やプラットフォームに。そうして理論的には、安全な歩行者天国ができるわけです。ところが、自転車は自転車だけ、車は車だけ、歩行者は歩行者だけといったアパルトヘイト的システムよりも、時には異なる交通手段が同じ道路を共有する方が、簡潔で快適であることに私たちはほどなくして気づくのです。こうした考え方は、少し時が経ってからポストモダニズムとともにでてくるものですね。異なる交通手段である自転車、歩行者、自動車を統合するための新しいストリートスケープをデザインしようというものです。実際このプラットフォームは、プロジェクトの中で一番最初に考えられたものでした。モダニズムは分離を目指していましたが、ポストモダニズムは統合を目指したのですね。

家の中における様々な活動の統合、それはどういったことを意味するのでしょうか?

ここ2、3年でわかってきたことですが、仕事に行くために家を出て、仕事を終えて家に戻り、それから映画や買い物に出かけるためにまた家を出る、といった考え方はもはや崩壊しているのでしょう。今こそ、私たちは、生活と仕事と余暇を同時に実現できるような場所を再発明するべきです。ちなみにそれは、産業革命以前の普通の生活様式のことでもあるのですが。

産業革命以前の時代に戻って考えてみましょう。それは、そんなに古い過去というわけではないのですが、オフィスは全てホームオフィスでしたよね。人々は家で働いていました。職人や大工、もっと言えば家具職人にシャツ職人、靴職人に帽子職人、仕立て屋さんにお針子さん... 彼らは住んでいる建物と同じ建物の中に、小さな店を構えていました。違う階に店を構えることもありました。鉄道が発明され、働きに出るという考えができる前は、そうやって生活していたのです。こうした先入観は、パンデミックで本当に変わりましたね。職人や大工、家具職人に加えて、保険ブローカーや医者、教師といったホワイトカラーの人たちも家で働くようになりました。そうして、誰が本当に「働きに出る」必要があり、誰が「家でも仕事ができる」のかがわかるようになりました。

もちろん、心理的な影響も無視できません。社会的存在としての私たちにとって、外出し人と会うことの必要性は、より理解され重要なこととして捉えられています。今日の新しいIT技術は、私たちが過去から受け継いできた近接性という概念や、コミュニティにおける「自然な」モデルというものを調査し、そこに挑戦していくことになるでしょう。

ところが、今日の市場原理は、より大きなオフィスを作り続けています。世界中の権力が、新しい地下鉄やオフィスビルの建設に投資し続けていますし、システムとして、それが都市に収益性をもたらす最も簡単な方法だと信じられているのです。

1922年には、オフィスビルを建てることは良いアイデアでした。データが集中的に管理されていた時代です。ところが今は2023年です。コンピューターのサーバーだけが集中的に管理されていて、データ管理の全ては遠隔地にあり、分散化されています。(つまり、たいていのオフィスワークはどこでもできるということです。)

人々が必要とするような家が建てられていない、ということですね。逆説的なことですね。

バービカン・エステートは、1956年に考案されました。人々が朝8時に家を出て仕事に行くという時代です。そして午後6時には家に帰ってくる。今でもそうしている人はいますが、だんだん減ってくるでしょうね。今こそ何か違うものが発明されるべきなのです。私たちが暮らし、働き、売り買いし、余暇を楽しむための新しい空間と新しい技術的インフラが必要とされているのです。それも、物理的な人的移動を最小限にし、人、材料、食料、商品などの機械的な輸送も削減できるような方法で。バービカンは、カーボンフットプリントのモニュメントなんですよ。だからこそ改修するのも難しいのでしょう。時が解決してくれるのかもしれませんが...

2022年9月15日

Mario Carpo: It’s an idea of the fifties, built in the sixties, that came to market in the seventies. The high rises of the Barbican estate were inaugurated only a few months before Charles Jencks published „The language of postmodern architecture”. That was the tipping point. Before 1977, the Barbican was the future. In 1977 the Barbican became the past.

IT IS A HOUSING COMPLEX THAT CAN BE LOVED AND HATED AT THE SAME TIME.

The spirit of modernism—the Frankenstein-like monster of post-war society’s techno-social imagination—was a strong proponent of the idea that individual housing should not exist. Instead, mass-produced and prefabricated apartments should serve as a template for standardised living. It was not only a pragmatic response to the conditions of a big city, pushing to build densely. It was an ideology of mass-production and economy of scale, addressed to modern men and women, supposed to be themselves standard products.

The Barbican Estate was the result of this modernist ideology: its vast scale, repetition, exposed concrete, and central heating system expressed clearly the credo of the fifties. Even though it was a relatively expensive complex addressed to the upper middle class, aesthetically and atmospherically it did not fit to its time. Starting from the late 1970s, its design was seen as the materialisation of a previous generation’s dreams.

Today, many perceive it to be a plain structure of 2000 affordable homes, they photograph, and study it as such, but nothing could be further from the truth. It is not and never was a social housing complex.

WHAT IS THE SOURCE OF THE MISCONCEPTION?

People think that brutalism was the style of social housing because social housing was built in concrete, which is why the Barbican is so popular among my students. But it’s only a nostalgia for the time when the state actually built social housing. But then, in 1979, Margaret Thatcher was elected and ushered in her ‘Right to Buy’ project - a policy that effectively eliminated social housing.

If you compare the Barbican Estate with other British social housing, evidently it was never meant to be one. It was more expensive from the start, and it had a more sophisticated design intention. It was not pure “techy” brutalism, so to speak, in Renyer Banham’s original sense of the term; and it was no longer international modernism. It is wacky and wonky; “artsy” in a sense. There was an ambition of ornamentation, decoration, it expressed a character.

…AND YOU WANTED TO GO BEYOND MERE OBSERVATION AND EXPLORE THE MODERNIST IDEOLOGY WITH YOUR SENSES AND EXPERIENCES, BY LIVING THERE FOR A FEW YEARS…

Yes, I wanted to try it. I am a tenant for life, so to speak--I don’t own real estate--and I have been fortunate enough to live, briefly, in some memorable residences. When I retire and look back on all my memories, I may put them all in a book.

As far as I am concerned, the Barbican Estate embodies the modernist ideology through its technical choices, rather than in its often-peculiar design.

The heating system, for a start. There is underfloor heating everywhere--and electric to boot, an unusual choice at the time, and at that scale. Chamberlain, Powell and Bon had this forward-thinking notion that heating should be ubiquitous, isotropic, homogenous, and invisible - underfloor - like magic! It would ensure permanent thermal comfort without any intervention from the tenants, without the residents even ever knowing where the heat came from. This was an ideal of modernism: a controllable nature. Enter any apartment and you’d always find a perfect temperature--which for Le Corbusier was meant to be 18 Celsius for all and forever. But then reality hit them hard; managing this type of system proved to be too costly, so estate management opted for a lower “background” temperature of 15 C instead – which isn’t warm enough. Moreover, the estate purchases electricity in bulk on the energy market when prices are low, and they heat their apartments from midnight to 6 a.m. This means that you wake up every day at 6 a.m., stepping into what feels like a sauna! And there is basically no heating during the day, so after 12 a.m. it starts to be too cold in winter. There are no gas pipes anywhere at the Barbican, therefore the only way to heat your apartment is an electric stove or space heater—dangerous and expensive. This seems hard to believe, but, although all underfloor heating in the estate is electric, there is no way to install a single thermostat--anywhere. You may open the windows when it’s too hot, and turn your electric stove on when it’s too cold, but otherwise you are left at the mercy of a ubiquitous, unstoppable system of centralised heating which is controlled by a remote, anonymous, centralised bureaucracy, ideally benevolent: almost a metaphor of the welfare state, where even heating is planned for all, from cradle to grave: heating by consensus and by committee. I discussed this argument at length in a recent article; you may read it here (https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)

To put it bluntly, the heating in the Barbican is a nightmare and that is one of the reasons why so much retrofitting has to be done when wealthy people buy these apartments and realise that it is not possible to adjust the heating.

In my opinion, a house should be a place where anyone can choose the thermal environment that best suits their needs. Whether you prefer it hot or cold, open windows or closed; the beauty of postmodernism is recognising that no two people are alike - and neither are their temperature preferences! Modernism believed in homogeneity; postmodernism didn’t.

WHAT ARE THE OTHER PROBLEMS OF THE BARBICAN ESTATE?

There is a phenomenon, a problem occurring particularly in the towers, which is incidentally where I lived, which I would call vertical gentrification. At the top of the high rises the tycoons, the billionaires, the oligarchs buy apartments, and combine two or three of them together. In practice, it leads to a permanent building site on the top floors. If you live in a building made of massive, reinforced concrete, you hear a spoon dropped on the 30th floor all the way down to the basement. Given that, think of builders drilling all day long, demolishing reinforced concrete or hanging suspended ceilings, remaking bathrooms. During the pandemic in particular, when we were all working from home, it was hell.

From what I have seen, the new prosperous residents of the Barbican are not pleased with its spartan style, wanting instead more luxurious and polished finishes. What’s more, even though the apartments were considered quite large in their time, they were planned with tiny bathrooms, likely due to the era’s spirit of frugality. Today’s affluent owners have different tastes; so bathrooms are being retrofitted.

For instance, in the tower where I lived during the pandemic, there was a kind of stone cutting shop installed on the top floors, for months on end, which consequently meant that one out of the three elevators was permanently used by the builders, going up and down, delivering slabs of marble.

In my opinion, this “vertical” gentrification is a result of a discrepancy of taste. The rich probably don’t like how the building looks, and they have no interest in brutalism of the 60s and 70s--which probably reminds them of social housing, even if the parallel is unwarranted in this instance. But they say the same of the Barbican towers as Zola said of the Eiffel Tower - the only way not to see it is to be on top of it. Due to the layout of the plan, each apartment has two or three aspects. It was until recently the tallest residential building in London - 41 floors. The view from the top is stunning, so the people buy the view and remake everything, which turns the life of all the residents below into a nightmare.

The complaints about noise, which is extreme in the high rises, seem to be manageable in the horizontal blocks, because the pressure of real estate there is not as strong. If you’re looking for a view from the top, you don’t have it. The apartments are smaller, cheaper. The oligarchs don’t buy the flats that really look like “middle class” social housing--which they were.

WHAT WERE YOUR POSITIVE EXPERIENCES? IS THERE SOMETHING THAT YOU FOUND FANTASTIC?

I told you the experience of a resident, noise, neighbours, etc. But, as an architect it is always good to be surrounded by design. I don’t always like the choices of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. At times it seems to me that they didn’t have the technology and the means to sustain their ambitions. However, in spite of these shortcomings, it is good to see a design intention all around you, when you wake up in the morning.

It doesn’t have to be the intention of an architect you like; it just needs to be driven by a vision. If you are a designer, or if you simply care about design intelligence, it is something that makes your life better.

In Barbican, the architects’ concrete tectonics are remarkable, very much in the spirit of Paul Rudolph. Even though I don’t particularly appreciate Paul Rudolph’s designs, it’s evident he was a great designer. When I taught at the Yale School of Architecture - an intimidatingly large concrete building by Rudolph - everything about it captivated my eyes, from its proportions to its craftsmanship. It’s clear that this structure has been carefully and skillfully built, first and foremost, in the mind of an architect--and an architect of genius. As I said, it doesn’t have to be a vision you share; its consistency and strength is enough to please one’s eyes and mind.

WHEN DO YOU FEEL AT HOME IN THE BARBICAN? IS IT WHEN YOU STEP OFF THE STREET AND INTO THE LOBBY, OR LATER WHEN YOU ARRIVE TO AND ENTER YOUR OWN APARTMENT?

Although I liked the lobby, it certainly didn’t feel like home. It felt more like waiting for a train at the station with people constantly coming and going. plus, there’s still that feeling of being in a public space surrounded by strangers. The doorman was always on duty, vigilantly keeping watch over the area.

But when you open your door and step inside, there’s a feeling of being right at home. It almost feels like magic! Imagine the experience of taking an elevator 120 meters up – it’s just as if you were climbing a mountain in the Alps. The clouds below feel so close that when they part to reveal the sun above, it is breathtaking - similar to being on an aeroplane with clouds beneath and sunshine reflecting off its wings!

All this comes after leaving the cavernous and almost chthonian, sinister darkness of the lobbies and elevators behind you; pushing through your front door leads into full sunlight. That was a pleasure.

AFTER FIVE YEARS OF LIVING THERE, HOW WELL DO YOU KNOW THE WHOLE COMPLEX?

The Barbican is famously labyrinthine. Every time you go out and cross the public plaza, someone will ask you: „excuse me, do you know how to get to…” Everyone is permanently lost. It is the result of the idea of a separation of traffics and the segregation of normal streets--which are replaced here by aerial pedestrian walkways. Meaning, there is the very intricate pedestrian platform, made of corridors, passageways, bridges, and balconies that are not at the scale of the city and must be learnt and not followed.

Chamberlain, Powell and Bon fully embraced the Corbusian modernist ideals of separating functions, and in particular, removing traffic. Cars are in tunnels and pedestrians are on bridges and platforms; in theory, a safe pedestrian paradise. Shortly thereafter we realised that sometimes it is easier and more pleasant to share the road with different traffics, rather than having an apartheid system whereby bicycles only meet bicycles, cars only cars and pedestrians, only other pedestrians. But this came a little later, with postmodernism: the idea to design a new streetscape meant to integrate different traffics: bicycles, pedestrian and cars. The platform is the element that dates the project the most. Modernism was about segregation; postmodernism has been about integration.

WHAT ABOUT INTEGRATION OF DIVERSE ACTIVITIES IN A HOUSE?

What we have learnt in the last two or three years is that the idea that you leave home to go to work and you come back home after you have been working and then you leave home, again, to go out to the movies, or go shopping, or whatever, has fallen apart. Now we need to reinvent a place where we can live and work and have fun at the same time, which by the way was the normal way of living before the industrial revolution.

Back then--in the pre-industrial age, which was not long ago--every office was a home office. People worked at home - artisans, carpenters, cabinet makers; shirtmakers, shoemakers, hatmakers, tailors, seamstresses... They had a little shop in the same building where they lived, sometimes on different floors. That’s the way they lived before we invented the railway and we decided that we needed to go and work in a different place. This preconceived idea has been truly challenged during the pandemic, when artisans, carpenters, cabinet makers were joined by white collar workers--insurance brokers, doctors, teachers. It showed who really needed to “go to work” and who could “work from home”.

Of course, we shouldn’t neglect the psychological effects, which are becoming more understood and consequential, the need and meaning for us as social beings, to go out, to meet other people. Today’s new IT (information technology) will inevitably probe and challenge the supposedly “natural” models of community and proximity we have inherited from the past.

Yet, today, market forces keep building bigger and bigger offices, authorities around the world are still investing in building new metro and subway lines and new office buildings, the system remains convinced that it is the easiest way to make cities profitable. It was perhaps a good idea to build office buildings in 1922, when data was centralised; now in 2023, only the computer server is centralised, all data management can be remote and despatialised (i.e., most office work can happen anywhere).

NOBODY IS BUILDING THE HOUSES PEOPLE NEED. THAT’S THE PARADOX.

The Barbican was conceived in 1956 when people left home at 8 a.m. to go to work. They came back home at 6 p.m. and some people will still do that, but fewer and fewer people will. It’s time to invent something different. We need new spaces, and new technical infrastructure’s that will allow people to live, work, shop and have fun with minimal physical displacement, and minimising the need for the mechanical transportation of people, raw materials, food, and goods. The Barbican, which is a monument to carbon footprint, may not be easy to retrofit for that purpose. Time will tell...

15.09.2022

马里奥-卡波: 这是一个50年代的想法,在60年代建造,在70年代进入市场。巴比肯住宅区的高层建筑在查尔斯-詹克斯(Charles Jencks)发表 《后现代建筑的语言》前几个月才开始启用。那是一个转折点。在1977年之前,巴比肯是未来。1977年,巴比肯成为了过去。

它是一个让人可以既爱又恨的住宅综合体。

现代主义的精神——战后社会的技术社会想象中弗兰肯斯坦般的怪物——坚定地支持独立住宅不应存在的观念。相反,大规模生产和预制的公寓应该作为标准化生活的模板。这不仅是对大城市条件的务实回应,推动了建筑的密集化。这是一种大规模生产和规模经济的意识形态,针对的是现代男女,他们被假定为标准化的产品。

巴比肯屋村是这种现代主义意识形态的结果:其巨大的规模、重复、裸露的混凝土和中央供暖系统明确表达了50年代的信条。尽管它是一个相对昂贵的建筑群,针对中上层阶级,但从美学和氛围上来说,它并不适合于它的时代。从70年代末开始,它的设计被视为上一代人梦想的具体化。

今天,许多人认为它是一个由2000套经济适用房组成的普通构筑物,他们拍摄并研究它,但实际情况与此相去甚远。它从未是一个社会住房综合体,也永远不是。

这种误解的根源是什么?

人们认为粗野主义是社会住房的风格,因为社会住房是用混凝土建造的,这就是为什么巴比肯在我的学生中如此受欢迎。但这只是对国家实际上建造社会住房时代的怀旧。但后来在1979年,玛格丽特-撒切尔当选,并迎来了她的 "购买权 "项目——这项政策实际上消除了社会住房。

如果你将巴比肯屋村与其他英国社会住房进行比较,显然它从来就不是为了成为一个社会住房。它从一开始就更为昂贵,而且具有更复杂的设计意图。它不是纯粹的 "技术性 "粗野主义,可以说是雷尼尔-班纳姆最初意义上的粗野主义;它也不再是国际现代主义。 它是古怪的,不稳定的;在某种意义上是 "艺术的"。它具有修饰,装饰的野心,它表达了一种性格。

...而你想超越单纯的观察,用你的感官和经验来探索现代主义的意识形态,在那里生活几年...

是的,我想试试。我是个终身租户,可以这么说——我不拥有房地产——我有幸在一些令人难忘的住所中短暂的居住过。当我退休并回顾我所有的记忆时,我可能会把它们都写进一本书。

在我看来,巴比肯屋村通过其技术选择,而不是其通常特别的设计,体现了现代主义的思想。

首先是供暖系统。 巴比肯住宅区使用的是通铺的电地暖,这在当时以及那样的规模下是一种不寻常的选择。张伯伦、鲍威尔和本恩公司有一个具有前瞻性的概念,即供暖应该是无处不在的、各向同性的、均匀的和无形的——地板下的——就像魔术一样!这将确保恒温舒适,而不需要在地面上留下痕迹,也不需要住户的任何干预,甚至他们都不知道热量从何而来。这是现代主义的一个理想:一个可控制的自然。进入任何一间公寓,你都能感受到完美的温度——对勒-柯布西耶来说,这个温度应该是18摄氏度,永远适用于所有人。 但是,现实给了他们沉重的打击;管理这种类型的系统被证明太昂贵了,所以屋村管理部门选择了一个较低的 "背景 "温度,即15摄氏度——这并不够温暖。此外,当价格低的时候,屋村在能源市场上大量购买电力,他们从午夜到早上6点为公寓供暖。这意味着你每天早上6点醒来时,仿佛置身于桑拿房中!白天基本上没有供暖,所以午夜后的冬季会变得太冷。巴比肯屋村没有任何煤气管道,因此你只能通过使用电炉或电暖器来加热你的公寓——危险且昂贵。这似乎难以置信,但是,尽管屋村里所有的地暖都是电动的,但没有办法安装单独的温控器——在任何地方。 你可以在太热的时候打开窗户,在太冷的时候打开电炉,但除此之外,你只能任由一个无处不在、不可阻挡的集中供暖系统摆布,这个系统由一个遥远的、匿名的、集中的官僚机构控制,理想上是仁慈的:几乎是福利国家的一个隐喻,在那里,甚至供暖都是为所有人规划的,从摇篮到坟墓:通过共识和委员会供暖。 我在最近的一篇文章中详细讨论了这个论点;你可以在这里阅读(https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)。

直截了当地说,巴比肯的供暖是一场噩梦,这也是为什么当富人买下这些公寓并意识到不可能调节供暖时,必须进行如此多改造的原因之一。

在我看来,住宅应该是一个任何人都可以选择最适合自己需求的热环境的地方。无论你喜欢热的还是冷的,开窗还是关窗;后现代主义的魅力在于认识到没有两个人是相同的——他们的温度偏好也是如此! 现代主义相信同质性;后现代主义不相信。

巴比肯屋村的其他问题是什么?

有一个现象,一个特别发生在塔楼上的问题,也就是我住过的地方,我称之为垂直士绅化。在高层建筑的顶层,富豪、亿万富翁、寡头购买公寓,并将其中的两到三套组合在一起。在实践中,它导致了在顶层的永久建筑工地。如果你住在一栋由巨大的钢筋混凝土制成的大楼里,你会听到一个勺子从30楼一直掉到地下室的声音。鉴于此,想象一下建筑工人整天钻孔、拆除钢筋混凝土或悬挂吊顶、重修浴室。 特别是在疫情期间,当我们都在家里工作时,那真是地狱。

据我所见,巴比肯繁荣的新居民并不满意其简陋的风格,而是想要更豪华和精致的装饰。更重要的是,尽管这些公寓在当时被认为是相当大的,但浴室被规划的很小,可能是由于那个时代的节俭精神。如今的富裕业主有着不同的品味;因此,浴室正在被改造。

例如,在疫情期间我居住的塔楼里,顶层安装了一个石材切割车间,持续了数月,这就意味着三部电梯中的一部被建筑承包商长期使用,上上下下,运送大理石板。

在我看来,这种 "垂直 "的士绅化是一种品味差异的结果。有钱人可能不喜欢这个建筑的外观,他们对60年代和70年代的粗野主义没有兴趣——这会让他们想起了社会住房,即使在这个例子中这种类比是没有必要的。 但他们对巴比肯塔楼的评价和左拉对埃菲尔铁塔的评价一样——不看它的唯一方法就是站在它的上面。由于平面布局,每个公寓都有两个或三个朝向。直到最近,它还是伦敦最高的住宅楼——41层。从顶部看去,景色令人惊叹,因此人们购买了视野并改造了一切,这让下面所有居民的生活变成了一场噩梦。

关于噪音的投诉,在高层建筑中是很极端的,而在水平向的街区中似乎是可以控制的,因为那里的房地产压力没有那么大。如果你想从顶层看风景,那是无法实现的。公寓更小更便宜。寡头们不会购买那些真的看起来像 "中产阶级 "社会住房的公寓——因为它们曾经确实如此。

你的积极经验是什么?有什么是你觉得不可思议的吗?

我告诉你一个居民的经验,噪音,邻居,等等。但是,作为一个建筑师,被设计所包围总是好的。我并不总是喜欢张伯伦、鲍威尔和本恩公司的选择。有时候我觉得他们没有技术和手段来支持他们的抱负。然而,尽管存在这些缺点,早上醒来时看到周围都是设计意图还是很好的。

这个意图不一定是你喜欢的建筑师的意图,它只需要由一个愿景驱动。如果你是一个设计师,或者你只是关心设计的智慧,它会让你的生活变得更美好。

在巴比肯,建筑师们的混凝土构造是非常了不起的,非常符合保罗-鲁道夫的精神。尽管我并不特别欣赏保罗-鲁道夫的设计,但很明显他是一个伟大的设计师。当我在耶鲁大学建筑学院教书时——那座鲁道夫设计的令人生畏的大型混凝土建筑——从比例到工艺,它的一切都吸引着我的眼睛。很明显,这个结构首先是在一位建筑师的头脑中精心而熟练地建造的——而且是一位天才的建筑师。 正如我所说的,它不一定是你的共同愿景;它的一致性和力量足以让人眼前一亮,心生赞叹。

在巴比肯,你什么时候有家的感觉?是在你离开街道进入大堂的时候,还是在你到达并进入自己的公寓后?

虽然我喜欢那个大堂,但它肯定没有家的感觉。它更像是在车站等火车,人们不断地进进出出。另外,还有那种置身于公共空间被陌生人包围的感觉。门卫总是在值班,警惕地看守着这个区域。

但当你打开自家的门,踏进去的时候,有一种立刻到家的感觉。这几乎是一种神奇的感觉! 想象一下乘坐电梯上升120米的体验——就像你在阿尔卑斯山上爬山一样。下面的云层感觉如此之近,以至于当它们分开,露出上面的太阳时,令人叹为观止——类似于在飞机上,云层在下面,阳光从机翼上反射出来!

所有这一切都发生在你离开了洞穴般阴暗险恶的大堂和电梯的时刻之后;推开你的前门走进充满阳光的屋内。这是一种愉悦的感觉。

在那里生活了五年之后,你对整个建筑群的了解程度如何?

巴比肯屋村是因其迷宫般的布局而闻名。每次你出门,穿过公共广场,都会有人问你: "对不起,你知道怎么去..." 每个人都会永远的在迷路。这是交通分离和隔离正常街道想法的结果,街道在这里被空中人行道所取代。意思是说,这里有非常复杂的人行平台,由走廊、通道、桥梁和阳台组成,它们不符合城市的尺度,必须学习而不是遵循。

张伯伦、鲍威尔和本恩完全接受了柯布西耶式的现代主义理想,即分离功能,特别是消除交通。汽车在隧道里,行人在桥梁和平台上;理论上,这是一个安全的行人天堂。此后不久,我们意识到,有时与不同的交通方式共享道路会更容易、更令人愉快,而不是有一个隔离制度,即自行车只能遇到自行车,汽车只能遇到汽车,行人只能遇到其他行人。但这是后来才有的,是后现代主义:旨在设计一个新的街景,整合不同的交通方式:自行车、行人和汽车。平台是该项目最具时代特征的元素。现代主义是关于隔离的;后现代主义是关于整合的。

那么,在一个住宅里不同活动的整合呢?

在过去的两三年里,我们学到的是,你离开家去工作,工作后回到家,然后再次离开家,去看电影,或去购物,或其他,这种想法已经崩溃了。现在,我们需要重新创造一个我们可以同时生活、工作并享受乐趣的地方,顺便说一下,这是工业革命之前正常的生活方式。

那时——在前工业时代,也就是不久前——每个办公室都是家庭办公。人们在家里工作——工匠、木匠、橱柜制造商;衬衫制造商、鞋匠、帽子制造商、裁缝、女裁缝...... 他们在自己居住的同一栋楼里有一个小店,有时在不同的楼层。这就是他们在我们发明铁路之前的生活方式,我们决定我们需要去不同的地方工作。这种先入为主的想法在疫情期间受到了真正的挑战,这时白领工人——保险经纪人、医生、教师加入了工匠、木匠、橱柜制造商。这表明谁真正需要 "去工作",谁可以 "在家里工作"。

当然,我们不应该忽视心理上的影响,这些影响正变得越来越被人理解和重视,我们作为社会人,走出去,认识其他人的需求和意义。 今天的新IT(信息技术)将不可避免地探索和挑战我们从过去继承下来的所谓 "自然 "的社区和接近模式。

然而,今天,市场力量不断地建造越来越大的办公室,世界各地的当局仍然在投资建设新的地铁线路和办公楼,系统仍坚信这是使城市盈利的最简单的方式。

在1922年,建造办公楼也许是个好主意,当时数据是集中的;现在到了2023年,只有计算机服务器是集中的,所有的数据管理都可以是远程和去空间化的(也就是说,大多数办公室工作可以在任何地方进行)。

没有人在建造人们需要的住宅。这就是矛盾之处。

巴比肯屋村是在1956年构思的,当时人们早上8点离开家去工作,下午6点回家,有些人仍然会这样做,但越来越少的人会如此。现在是发明一些不同的东西的时候了。我们需要新的空间和新的技术基础设施,让人们在生活、工作、购物和娱乐的同时,尽量减少物理位移,并尽量减少对人员、原材料、食品和货物的机械运输的需求。 巴比肯屋村是一个碳足迹的纪念碑,可能不容易进行改建以适应这一目的。 时间会告诉我们...

2022年9月15日

マリオ・カルポ: アイデアは50年代のものですが、建てられたのは60年代のことです。そして市場に出回ったのは70年代のことです。バービカン・エステートが竣工したのは、チャールズ・ジェンクスが『ポスト・モダニズムの建築言語』を発表したほんの数ヶ月前のことですから、ちょうど転換期だったのでしょう。1977年以前には、バービカンは未来にあり、1977年には過去のものとなってしまった。

バービカンは愛されていましたが、同時に憎まれてもいた、と。

モダニズムの精神。戦後技術社会の想像力が生み出したフランケンシュタイン的怪物。それは、個人住宅など存在すべきではないと強く提唱していました。その代わりに、大量生産されたプレファブの集合住宅が、標準的生活のテンプレートとして機能するはずである、と。それは、高密化する大都市の現状への単なる現実的な対応にとどまるものではありませんでした。マスプロダクションやスケールメリットのイデオロギーとして、近代的男性、そして女性へと差し向けられたものでした。それ自体が標準的なプロダクトとしてね。

バービカン・エステートは、モダニストのイデオロギーの成果なのです。その広大なスケール、反復、剥き出しのコンクリート、そしてセントラルヒーティング。50年代的な信条が明確に表現されています。比較的高価な集合住宅として、上位中産階級をターゲットにしていましたが、美的にも雰囲気的にも時代に沿ったものではなかったのです。それが、昔の世代の夢の具現化として認識され始めたのは、1970年代の後半からです。

今では多くの人が、2000戸の「手頃なおうち」の並んだ平凡な建物だと思っていますし、そうやって撮影したり、研究したりしています。でもね、見当違いなんです。ソーシャルハウジングの類いでは全くないのですから。

なぜ、そのように理解されてしまっているのでしょうか?

ブルータリズムのことを、ソーシャルハウジングのスタイルだと勘違いしているのでしょう。コンクリートで建てられていますから。だからバービカン・エステートは学生にも人気がある。ただそれも、国が本当にソーシャルハウジングを建設していた時代へのノスタルジーに過ぎないのだと思います。1979年にマーガレット・サッチャーが当選し「買う権利」プロジェクトを導入したわけですが、ソーシャルハウジングは、事実上この政策によって抹消されてしまいましたね。

バービカン・エステートをイギリスの他のソーシャルハウジングと比較してみてください。全然違いますね。竣工時から高価なものでしたし、洗練されたデザインの意図があるのがわかるでしょう。純粋に「テッキー(技術オタク)」なブルータリズムではない。まさにレイナー・バンハムが本来の意味で用いたような意味でね。それにインターナショナルモダニズムでもない。ワッキー(へろへろ)でウォンキー(ふらふら)で、ある意味「アーツィー(芸術気取り)」だとも言える。オーナメントやデコレーションに対する野心が滲みでています。

…あなたはバービカンをただ鑑賞するだけでなく、そのモダニストのイデオロギーをご自身の感覚と経験によって探求しようとされたのですよね。つまり、数年間そこに住んでおられたわけですが...

まさに。体験してみたかったのです。私は生涯、借家人ですので不動産を持っていません。幸運なことに、短い間でしたが、これまでにも記憶に残るような住宅に住むことができました。リタイアしたら今までの思い出を振り返って、一冊の本にまとめたりするかもしれませんね。

私の考えでは、バービカン・エステートはその奇怪なデザインよりもむしろ、技術的な選択によってモダニストのイデオロギーが体現されているのだと思います。

まず第一にヒーティングシステムがありますよね。あらゆるところが床暖房になっていて、しかも電気式です。当時としては珍しい。しかもこの規模で。チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンの3人は、先進的な考えを持っていたのでしょう。暖房システムは、偏在的で、等方的で、均質的で、そして見えないものであるべきだ、と。つまり床下に。魔法のようにね!入居者の手を煩わせることなく、恒久的で快適な熱環境を提供してくれるのです。居住者は熱がどこから出てきているのか、知る必要すらありません。モダニズムの理想、つまりコントロール可能な自然がここにあるのです。どの部屋にいても完璧な気温を手に入れられる。ル・コルビュジエにとっては、全ての人が18度という温度を永遠に手にすることができる、ということを意味していました。ところが、現実は厳しいもので、システムの管理にコストがかかりすぎることが判明したのです。そこで不動産管理者は、温度を下げて15℃という「バックグラウンド」温度に設定したのですが、それでは十分に暖かくはならないのです。しかも、電気は市場から大量に安く購入され、部屋が暖められるのは深夜から朝の6時の間のみです。だから毎朝6時に起きると、サウナに入ったみたいになっているんです!日中は基本的に暖房がないでしょう。ですから、12時を超えると冬は寒くてたまらないですね。ガス管も通っていないので、暖房は電気式ストーブかスペースヒーターしかありません。危険ですし高価ですよね。床暖房は全て電気式なのですが、信じられないことに、サーモスタット(温度調整装置)を一つも設置できないんです。暑いときは窓を開けて、寒いときは電気ストーブをつける。さもなくば、このセントラルヒーティングシステムのなすがままに。このシステムはあらゆるところで作動していて、止めることができません。遠隔地で匿名の誰かが、中央集権的な手続きのもとにコントロールしているのです。慈善の精神でね。ほとんど福祉国家のメタファーのようですよ。全ての人に暖房を。揺り籠から墓場まで。委員会の同意のもとに。この議論に関しては、最近の記事で詳しく述べているので、ぜひご一読ください。(https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)

はっきり言ってバービカンの暖房システムは悪夢ですよ。ここでは、たくさん改修工事が行われていますが、金持ちな人は、部屋を買ったはいいものの、暖房調整がうまく行かないと気づいて改修するのでしょう。

私は、家は誰もが自分のニーズに合った温熱環境を選ぶことのできる場所であるべきだと思います。暑いのが好きなのか、寒いのが好きなのか、窓を開けたいのか、それとも閉めたいのか、そういったことが選択できるということです。ポストモダニズムの美学は、決して同じ二人など存在しないということを認めているのです。温熱環境の好みもそうでしょう!モダニズムは、均質性を信じていましたが、ポストモダニズムは違います。

バービカン・エステートで他に問題は感じましたか?

特にタワー型マンションで生じるような現象は問題ですね。私の住んでいたところが、まさにそうなのですが、私はそれをバーティカル・ジェントリフィケーションと呼んでいます。タワーマンションの最上階は、実業家や大金持ち、それにオリガルヒが二つや三つ部屋を買って繋げたりするでしょう。つまり最上階では、常に建築現場が動いているということです。巨大な鉄筋コンクリートの建物に住んでいるとわかりますが、30階で落としたスプーンの音は、そのまま下に降りて地下階まで響きます。業者が1日中ドリルで穴を開けたり、コンクリートを解体したり、天井を吊ったり、バスルームを作り替えたりしていることを考えてみてくださいよ。特にパンデミックの時は、みんな在宅勤務でしたから地獄でしたよ。

私の拝見した限り、バービカンのこのスパルタンスタイルは、新しい住人たちのお気に召さないのでしょう。もっと豪華で洗練された仕上げを望んでいるのです。それに、部屋の大きさは当時としては、非常に大きいのですが、時代の倹約精神からかバスルームがかなり小さく設計されていますし、現代の裕福なオーナーは好みが違いますから、バスルームも改修せざるを得ないのでしょう。

例えば、パンデミック時に私が住んでいたタワーでは、最上階に石材のカットショップのようなものが数ヶ月も設置されていました。しまいには、業者が大理石の板を上げ下げするために、三台あるエレベーターのうちの一台が占領されてしまっていました。

この「バーティカル」ジェントリフィケーションは、好みの不一致から生じているのだと思います。金持ちはこの外観が気に入らないのだと思いますし、60年代や70年代のブルータリズムにも興味がないのだと思います。比較するのもおかしいのですが、たぶんソーシャルハウジングを連想させてしまうのでしょうね。それでも彼らは、ゾラがエッフェル塔について述べたように、このバービカンのタワーについてもこう述べるのです。その姿を見たくないのであれば、その頂上にいればいいのだ、と。平面的には、それぞれの部屋は二面、あるいは三面に眺望をもっています。それに、最近までロンドンで最も背の高い41階建てのマンションでした。上からの眺めは素晴らしいですよ。人々は眺望を買うのです。そうして部屋のあらゆるところは作り替えられ、階下の全ての住人の生活は悪夢へと変わってしまうのです。

騒音に対する苦情は、特にタワー棟の方でひどいのですが、水平ブロックの棟では、それほどでもないようですね。不動産の圧力もそれほど強くないのでしょう。こちらは狭くて安いですし、上からの眺望は手に入りません。オリガルヒは、まさにこういった「中流階級」向けに見えるソーシャルハウジングなんて買いません。いや、実際そうなんですけどね。

何かポジティブな経験は得られましたか?特に素晴らしいと感じられたことなどはありますか?

騒音や隣人など、住人のことについては、お話してきましたね。建築家としては、デザインに囲まれているということは、常に良いことだと思います。チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンのデザインが、私の好みだというわけではありませんが。それに当時の彼らは、野心をカバーする技術や手段を持ち合わせていなかったように感じます。そういった欠点を差し置いても、朝起きて身の回りがデザインにあふれているのは良いことです。

それが好きな建築家のものでなくともね。そこにヴィジョンがあればいいのです。あなたがデザイナーであったり、デザイン的な知性を気にするような人であるのなら、それだけで人生は豊かになりますよね。

バービカンでは、建築家によるコンクリートのテクトニクスが目を惹きます。明らかにポール・ルドルフの精神を受け継いでいますね。私は、ポール・ルドルフのデザインを特に評価しているわけではありませんが、彼が偉大なデザイナーであることは確かです。イエール大学の建築学部で教えていたことがあるのですが、ルドルフの威圧的なほどに巨大なコンクリート造の建築に、私の目は完全に魅了されてしまいました。プロポーションの素晴らしさや、そこで発揮されたクラフトマンシップに至るまで全てが素晴らしかった。この構築物は、緻密に、そして実によく作られたものであることは明らかです。しかもそれは最初から、そしてもっとも重要なことですが、建築家の頭の中にあったものなのです。天才的ですよ。先ほども言いましたが、そのヴィジョンは共有されるものでなくても良いのです。人の目と心を満足させるには、そこに一貫性と力強さがあれば十分です。

バービカン・エステートでは、どんな時に家にいてくつろぎを感じますか?通りからロビーに入る時でしょうか?それとも自分の部屋に入る時でしょうか?

ロビーは気に入っているのですが、家にいる感じはしませんでした。常に人が行き来していたので、駅で電車を待っているような感じに近いですね。見知らぬ人に囲まれたパブリックスペースのような感じでしょうか。ドアマンは常に勤務していましたし、しっかり管理してくれていました。

ですが、部屋のドアを開けて中に入ると、すぐに自分の家にいる感覚になれるのです。魔法にかけられたように!エレベーターで120メートル上まで行くことを想像してみてください。まるでアルプスの山に登っているような感覚です。眼下に広がる雲はとても近くに感じられ、雲の上に太陽が顔を出す瞬間は、息を呑むほどです。雲を眼下に、太陽の光が翼にきらめく飛行機にいるのと同じようにね!洞窟的でほとんど地面下にいるような、あの不吉にも暗いロビー、そしてエレベーターの先にそんな光景がやって来るのです。玄関のドアを開けると、陽光が降り注ぐ。喜びに溢れる瞬間です。

5年間の生活を通して、この建物についてはどれくらい把握することができましたか?

バービカンは立派な迷宮ですよ。外にでて広場を横切るたびに、誰かが訪ねてくるでしょう。「すみません。どこどこへの行き方をご存知ですか」と。誰もが永遠に迷子になっている。交通手段を分離することで、普通道路から隔離するというアイデアがそうさせているのです。ここでは空中の歩行者専用通路が用意されているのですが、それがまた非常に入り組んだ歩行者用プラットフォームなんです。プラットフォームは廊下や通路、橋やバルコニーで構成されていますが、どれも都市のスケールにはないものです。ですから、ただ従えば良いわけではなく、使い方を学んでいかないといけないのです。

チェンバレン、パウエル、ボンは、機能の分離というコルビュジエ的なモダニズムの理想を完全に取り入れようとしていたのだと思います。特に車の交通を排除するということに関してはそうですね。車はトンネルに。歩行者は橋やプラットフォームに。そうして理論的には、安全な歩行者天国ができるわけです。ところが、自転車は自転車だけ、車は車だけ、歩行者は歩行者だけといったアパルトヘイト的システムよりも、時には異なる交通手段が同じ道路を共有する方が、簡潔で快適であることに私たちはほどなくして気づくのです。こうした考え方は、少し時が経ってからポストモダニズムとともにでてくるものですね。異なる交通手段である自転車、歩行者、自動車を統合するための新しいストリートスケープをデザインしようというものです。実際このプラットフォームは、プロジェクトの中で一番最初に考えられたものでした。モダニズムは分離を目指していましたが、ポストモダニズムは統合を目指したのですね。

家の中における様々な活動の統合、それはどういったことを意味するのでしょうか?

ここ2、3年でわかってきたことですが、仕事に行くために家を出て、仕事を終えて家に戻り、それから映画や買い物に出かけるためにまた家を出る、といった考え方はもはや崩壊しているのでしょう。今こそ、私たちは、生活と仕事と余暇を同時に実現できるような場所を再発明するべきです。ちなみにそれは、産業革命以前の普通の生活様式のことでもあるのですが。

産業革命以前の時代に戻って考えてみましょう。それは、そんなに古い過去というわけではないのですが、オフィスは全てホームオフィスでしたよね。人々は家で働いていました。職人や大工、もっと言えば家具職人にシャツ職人、靴職人に帽子職人、仕立て屋さんにお針子さん... 彼らは住んでいる建物と同じ建物の中に、小さな店を構えていました。違う階に店を構えることもありました。鉄道が発明され、働きに出るという考えができる前は、そうやって生活していたのです。こうした先入観は、パンデミックで本当に変わりましたね。職人や大工、家具職人に加えて、保険ブローカーや医者、教師といったホワイトカラーの人たちも家で働くようになりました。そうして、誰が本当に「働きに出る」必要があり、誰が「家でも仕事ができる」のかがわかるようになりました。

もちろん、心理的な影響も無視できません。社会的存在としての私たちにとって、外出し人と会うことの必要性は、より理解され重要なこととして捉えられています。今日の新しいIT技術は、私たちが過去から受け継いできた近接性という概念や、コミュニティにおける「自然な」モデルというものを調査し、そこに挑戦していくことになるでしょう。

ところが、今日の市場原理は、より大きなオフィスを作り続けています。世界中の権力が、新しい地下鉄やオフィスビルの建設に投資し続けていますし、システムとして、それが都市に収益性をもたらす最も簡単な方法だと信じられているのです。

1922年には、オフィスビルを建てることは良いアイデアでした。データが集中的に管理されていた時代です。ところが今は2023年です。コンピューターのサーバーだけが集中的に管理されていて、データ管理の全ては遠隔地にあり、分散化されています。(つまり、たいていのオフィスワークはどこでもできるということです。)

人々が必要とするような家が建てられていない、ということですね。逆説的なことですね。

バービカン・エステートは、1956年に考案されました。人々が朝8時に家を出て仕事に行くという時代です。そして午後6時には家に帰ってくる。今でもそうしている人はいますが、だんだん減ってくるでしょうね。今こそ何か違うものが発明されるべきなのです。私たちが暮らし、働き、売り買いし、余暇を楽しむための新しい空間と新しい技術的インフラが必要とされているのです。それも、物理的な人的移動を最小限にし、人、材料、食料、商品などの機械的な輸送も削減できるような方法で。バービカンは、カーボンフットプリントのモニュメントなんですよ。だからこそ改修するのも難しいのでしょう。時が解決してくれるのかもしれませんが...

2022年9月15日

Mario Carpo: It’s an idea of the fifties, built in the sixties, that came to market in the seventies. The high rises of the Barbican estate were inaugurated only a few months before Charles Jencks published „The language of postmodern architecture”. That was the tipping point. Before 1977, the Barbican was the future. In 1977 the Barbican became the past.

IT IS A HOUSING COMPLEX THAT CAN BE LOVED AND HATED AT THE SAME TIME.

The spirit of modernism—the Frankenstein-like monster of post-war society’s techno-social imagination—was a strong proponent of the idea that individual housing should not exist. Instead, mass-produced and prefabricated apartments should serve as a template for standardised living. It was not only a pragmatic response to the conditions of a big city, pushing to build densely. It was an ideology of mass-production and economy of scale, addressed to modern men and women, supposed to be themselves standard products.

The Barbican Estate was the result of this modernist ideology: its vast scale, repetition, exposed concrete, and central heating system expressed clearly the credo of the fifties. Even though it was a relatively expensive complex addressed to the upper middle class, aesthetically and atmospherically it did not fit to its time. Starting from the late 1970s, its design was seen as the materialisation of a previous generation’s dreams.

Today, many perceive it to be a plain structure of 2000 affordable homes, they photograph, and study it as such, but nothing could be further from the truth. It is not and never was a social housing complex.

WHAT IS THE SOURCE OF THE MISCONCEPTION?

People think that brutalism was the style of social housing because social housing was built in concrete, which is why the Barbican is so popular among my students. But it’s only a nostalgia for the time when the state actually built social housing. But then, in 1979, Margaret Thatcher was elected and ushered in her ‘Right to Buy’ project - a policy that effectively eliminated social housing.

If you compare the Barbican Estate with other British social housing, evidently it was never meant to be one. It was more expensive from the start, and it had a more sophisticated design intention. It was not pure “techy” brutalism, so to speak, in Renyer Banham’s original sense of the term; and it was no longer international modernism. It is wacky and wonky; “artsy” in a sense. There was an ambition of ornamentation, decoration, it expressed a character.

…AND YOU WANTED TO GO BEYOND MERE OBSERVATION AND EXPLORE THE MODERNIST IDEOLOGY WITH YOUR SENSES AND EXPERIENCES, BY LIVING THERE FOR A FEW YEARS…

Yes, I wanted to try it. I am a tenant for life, so to speak--I don’t own real estate--and I have been fortunate enough to live, briefly, in some memorable residences. When I retire and look back on all my memories, I may put them all in a book.

As far as I am concerned, the Barbican Estate embodies the modernist ideology through its technical choices, rather than in its often-peculiar design.

The heating system, for a start. There is underfloor heating everywhere--and electric to boot, an unusual choice at the time, and at that scale. Chamberlain, Powell and Bon had this forward-thinking notion that heating should be ubiquitous, isotropic, homogenous, and invisible - underfloor - like magic! It would ensure permanent thermal comfort without any intervention from the tenants, without the residents even ever knowing where the heat came from. This was an ideal of modernism: a controllable nature. Enter any apartment and you’d always find a perfect temperature--which for Le Corbusier was meant to be 18 Celsius for all and forever. But then reality hit them hard; managing this type of system proved to be too costly, so estate management opted for a lower “background” temperature of 15 C instead – which isn’t warm enough. Moreover, the estate purchases electricity in bulk on the energy market when prices are low, and they heat their apartments from midnight to 6 a.m. This means that you wake up every day at 6 a.m., stepping into what feels like a sauna! And there is basically no heating during the day, so after 12 a.m. it starts to be too cold in winter. There are no gas pipes anywhere at the Barbican, therefore the only way to heat your apartment is an electric stove or space heater—dangerous and expensive. This seems hard to believe, but, although all underfloor heating in the estate is electric, there is no way to install a single thermostat--anywhere. You may open the windows when it’s too hot, and turn your electric stove on when it’s too cold, but otherwise you are left at the mercy of a ubiquitous, unstoppable system of centralised heating which is controlled by a remote, anonymous, centralised bureaucracy, ideally benevolent: almost a metaphor of the welfare state, where even heating is planned for all, from cradle to grave: heating by consensus and by committee. I discussed this argument at length in a recent article; you may read it here (https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)

To put it bluntly, the heating in the Barbican is a nightmare and that is one of the reasons why so much retrofitting has to be done when wealthy people buy these apartments and realise that it is not possible to adjust the heating.

In my opinion, a house should be a place where anyone can choose the thermal environment that best suits their needs. Whether you prefer it hot or cold, open windows or closed; the beauty of postmodernism is recognising that no two people are alike - and neither are their temperature preferences! Modernism believed in homogeneity; postmodernism didn’t.

WHAT ARE THE OTHER PROBLEMS OF THE BARBICAN ESTATE?

There is a phenomenon, a problem occurring particularly in the towers, which is incidentally where I lived, which I would call vertical gentrification. At the top of the high rises the tycoons, the billionaires, the oligarchs buy apartments, and combine two or three of them together. In practice, it leads to a permanent building site on the top floors. If you live in a building made of massive, reinforced concrete, you hear a spoon dropped on the 30th floor all the way down to the basement. Given that, think of builders drilling all day long, demolishing reinforced concrete or hanging suspended ceilings, remaking bathrooms. During the pandemic in particular, when we were all working from home, it was hell.

From what I have seen, the new prosperous residents of the Barbican are not pleased with its spartan style, wanting instead more luxurious and polished finishes. What’s more, even though the apartments were considered quite large in their time, they were planned with tiny bathrooms, likely due to the era’s spirit of frugality. Today’s affluent owners have different tastes; so bathrooms are being retrofitted.

For instance, in the tower where I lived during the pandemic, there was a kind of stone cutting shop installed on the top floors, for months on end, which consequently meant that one out of the three elevators was permanently used by the builders, going up and down, delivering slabs of marble.

In my opinion, this “vertical” gentrification is a result of a discrepancy of taste. The rich probably don’t like how the building looks, and they have no interest in brutalism of the 60s and 70s--which probably reminds them of social housing, even if the parallel is unwarranted in this instance. But they say the same of the Barbican towers as Zola said of the Eiffel Tower - the only way not to see it is to be on top of it. Due to the layout of the plan, each apartment has two or three aspects. It was until recently the tallest residential building in London - 41 floors. The view from the top is stunning, so the people buy the view and remake everything, which turns the life of all the residents below into a nightmare.

The complaints about noise, which is extreme in the high rises, seem to be manageable in the horizontal blocks, because the pressure of real estate there is not as strong. If you’re looking for a view from the top, you don’t have it. The apartments are smaller, cheaper. The oligarchs don’t buy the flats that really look like “middle class” social housing--which they were.

WHAT WERE YOUR POSITIVE EXPERIENCES? IS THERE SOMETHING THAT YOU FOUND FANTASTIC?

I told you the experience of a resident, noise, neighbours, etc. But, as an architect it is always good to be surrounded by design. I don’t always like the choices of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. At times it seems to me that they didn’t have the technology and the means to sustain their ambitions. However, in spite of these shortcomings, it is good to see a design intention all around you, when you wake up in the morning.

It doesn’t have to be the intention of an architect you like; it just needs to be driven by a vision. If you are a designer, or if you simply care about design intelligence, it is something that makes your life better.

In Barbican, the architects’ concrete tectonics are remarkable, very much in the spirit of Paul Rudolph. Even though I don’t particularly appreciate Paul Rudolph’s designs, it’s evident he was a great designer. When I taught at the Yale School of Architecture - an intimidatingly large concrete building by Rudolph - everything about it captivated my eyes, from its proportions to its craftsmanship. It’s clear that this structure has been carefully and skillfully built, first and foremost, in the mind of an architect--and an architect of genius. As I said, it doesn’t have to be a vision you share; its consistency and strength is enough to please one’s eyes and mind.

WHEN DO YOU FEEL AT HOME IN THE BARBICAN? IS IT WHEN YOU STEP OFF THE STREET AND INTO THE LOBBY, OR LATER WHEN YOU ARRIVE TO AND ENTER YOUR OWN APARTMENT?

Although I liked the lobby, it certainly didn’t feel like home. It felt more like waiting for a train at the station with people constantly coming and going. plus, there’s still that feeling of being in a public space surrounded by strangers. The doorman was always on duty, vigilantly keeping watch over the area.

But when you open your door and step inside, there’s a feeling of being right at home. It almost feels like magic! Imagine the experience of taking an elevator 120 meters up – it’s just as if you were climbing a mountain in the Alps. The clouds below feel so close that when they part to reveal the sun above, it is breathtaking - similar to being on an aeroplane with clouds beneath and sunshine reflecting off its wings!

All this comes after leaving the cavernous and almost chthonian, sinister darkness of the lobbies and elevators behind you; pushing through your front door leads into full sunlight. That was a pleasure.

AFTER FIVE YEARS OF LIVING THERE, HOW WELL DO YOU KNOW THE WHOLE COMPLEX?

The Barbican is famously labyrinthine. Every time you go out and cross the public plaza, someone will ask you: „excuse me, do you know how to get to…” Everyone is permanently lost. It is the result of the idea of a separation of traffics and the segregation of normal streets--which are replaced here by aerial pedestrian walkways. Meaning, there is the very intricate pedestrian platform, made of corridors, passageways, bridges, and balconies that are not at the scale of the city and must be learnt and not followed.

Chamberlain, Powell and Bon fully embraced the Corbusian modernist ideals of separating functions, and in particular, removing traffic. Cars are in tunnels and pedestrians are on bridges and platforms; in theory, a safe pedestrian paradise. Shortly thereafter we realised that sometimes it is easier and more pleasant to share the road with different traffics, rather than having an apartheid system whereby bicycles only meet bicycles, cars only cars and pedestrians, only other pedestrians. But this came a little later, with postmodernism: the idea to design a new streetscape meant to integrate different traffics: bicycles, pedestrian and cars. The platform is the element that dates the project the most. Modernism was about segregation; postmodernism has been about integration.

WHAT ABOUT INTEGRATION OF DIVERSE ACTIVITIES IN A HOUSE?

What we have learnt in the last two or three years is that the idea that you leave home to go to work and you come back home after you have been working and then you leave home, again, to go out to the movies, or go shopping, or whatever, has fallen apart. Now we need to reinvent a place where we can live and work and have fun at the same time, which by the way was the normal way of living before the industrial revolution.

Back then--in the pre-industrial age, which was not long ago--every office was a home office. People worked at home - artisans, carpenters, cabinet makers; shirtmakers, shoemakers, hatmakers, tailors, seamstresses... They had a little shop in the same building where they lived, sometimes on different floors. That’s the way they lived before we invented the railway and we decided that we needed to go and work in a different place. This preconceived idea has been truly challenged during the pandemic, when artisans, carpenters, cabinet makers were joined by white collar workers--insurance brokers, doctors, teachers. It showed who really needed to “go to work” and who could “work from home”.

Of course, we shouldn’t neglect the psychological effects, which are becoming more understood and consequential, the need and meaning for us as social beings, to go out, to meet other people. Today’s new IT (information technology) will inevitably probe and challenge the supposedly “natural” models of community and proximity we have inherited from the past.

Yet, today, market forces keep building bigger and bigger offices, authorities around the world are still investing in building new metro and subway lines and new office buildings, the system remains convinced that it is the easiest way to make cities profitable. It was perhaps a good idea to build office buildings in 1922, when data was centralised; now in 2023, only the computer server is centralised, all data management can be remote and despatialised (i.e., most office work can happen anywhere).

NOBODY IS BUILDING THE HOUSES PEOPLE NEED. THAT’S THE PARADOX.

The Barbican was conceived in 1956 when people left home at 8 a.m. to go to work. They came back home at 6 p.m. and some people will still do that, but fewer and fewer people will. It’s time to invent something different. We need new spaces, and new technical infrastructure’s that will allow people to live, work, shop and have fun with minimal physical displacement, and minimising the need for the mechanical transportation of people, raw materials, food, and goods. The Barbican, which is a monument to carbon footprint, may not be easy to retrofit for that purpose. Time will tell...

15.09.2022

马里奥-卡波: 这是一个50年代的想法,在60年代建造,在70年代进入市场。巴比肯住宅区的高层建筑在查尔斯-詹克斯(Charles Jencks)发表 《后现代建筑的语言》前几个月才开始启用。那是一个转折点。在1977年之前,巴比肯是未来。1977年,巴比肯成为了过去。

它是一个让人可以既爱又恨的住宅综合体。

现代主义的精神——战后社会的技术社会想象中弗兰肯斯坦般的怪物——坚定地支持独立住宅不应存在的观念。相反,大规模生产和预制的公寓应该作为标准化生活的模板。这不仅是对大城市条件的务实回应,推动了建筑的密集化。这是一种大规模生产和规模经济的意识形态,针对的是现代男女,他们被假定为标准化的产品。

巴比肯屋村是这种现代主义意识形态的结果:其巨大的规模、重复、裸露的混凝土和中央供暖系统明确表达了50年代的信条。尽管它是一个相对昂贵的建筑群,针对中上层阶级,但从美学和氛围上来说,它并不适合于它的时代。从70年代末开始,它的设计被视为上一代人梦想的具体化。

今天,许多人认为它是一个由2000套经济适用房组成的普通构筑物,他们拍摄并研究它,但实际情况与此相去甚远。它从未是一个社会住房综合体,也永远不是。

这种误解的根源是什么?

人们认为粗野主义是社会住房的风格,因为社会住房是用混凝土建造的,这就是为什么巴比肯在我的学生中如此受欢迎。但这只是对国家实际上建造社会住房时代的怀旧。但后来在1979年,玛格丽特-撒切尔当选,并迎来了她的 "购买权 "项目——这项政策实际上消除了社会住房。

如果你将巴比肯屋村与其他英国社会住房进行比较,显然它从来就不是为了成为一个社会住房。它从一开始就更为昂贵,而且具有更复杂的设计意图。它不是纯粹的 "技术性 "粗野主义,可以说是雷尼尔-班纳姆最初意义上的粗野主义;它也不再是国际现代主义。 它是古怪的,不稳定的;在某种意义上是 "艺术的"。它具有修饰,装饰的野心,它表达了一种性格。

...而你想超越单纯的观察,用你的感官和经验来探索现代主义的意识形态,在那里生活几年...

是的,我想试试。我是个终身租户,可以这么说——我不拥有房地产——我有幸在一些令人难忘的住所中短暂的居住过。当我退休并回顾我所有的记忆时,我可能会把它们都写进一本书。

在我看来,巴比肯屋村通过其技术选择,而不是其通常特别的设计,体现了现代主义的思想。

首先是供暖系统。 巴比肯住宅区使用的是通铺的电地暖,这在当时以及那样的规模下是一种不寻常的选择。张伯伦、鲍威尔和本恩公司有一个具有前瞻性的概念,即供暖应该是无处不在的、各向同性的、均匀的和无形的——地板下的——就像魔术一样!这将确保恒温舒适,而不需要在地面上留下痕迹,也不需要住户的任何干预,甚至他们都不知道热量从何而来。这是现代主义的一个理想:一个可控制的自然。进入任何一间公寓,你都能感受到完美的温度——对勒-柯布西耶来说,这个温度应该是18摄氏度,永远适用于所有人。 但是,现实给了他们沉重的打击;管理这种类型的系统被证明太昂贵了,所以屋村管理部门选择了一个较低的 "背景 "温度,即15摄氏度——这并不够温暖。此外,当价格低的时候,屋村在能源市场上大量购买电力,他们从午夜到早上6点为公寓供暖。这意味着你每天早上6点醒来时,仿佛置身于桑拿房中!白天基本上没有供暖,所以午夜后的冬季会变得太冷。巴比肯屋村没有任何煤气管道,因此你只能通过使用电炉或电暖器来加热你的公寓——危险且昂贵。这似乎难以置信,但是,尽管屋村里所有的地暖都是电动的,但没有办法安装单独的温控器——在任何地方。 你可以在太热的时候打开窗户,在太冷的时候打开电炉,但除此之外,你只能任由一个无处不在、不可阻挡的集中供暖系统摆布,这个系统由一个遥远的、匿名的、集中的官僚机构控制,理想上是仁慈的:几乎是福利国家的一个隐喻,在那里,甚至供暖都是为所有人规划的,从摇篮到坟墓:通过共识和委员会供暖。 我在最近的一篇文章中详细讨论了这个论点;你可以在这里阅读(https://mariocarpo.com/essays/central-heating)。

直截了当地说,巴比肯的供暖是一场噩梦,这也是为什么当富人买下这些公寓并意识到不可能调节供暖时,必须进行如此多改造的原因之一。

在我看来,住宅应该是一个任何人都可以选择最适合自己需求的热环境的地方。无论你喜欢热的还是冷的,开窗还是关窗;后现代主义的魅力在于认识到没有两个人是相同的——他们的温度偏好也是如此! 现代主义相信同质性;后现代主义不相信。

巴比肯屋村的其他问题是什么?

有一个现象,一个特别发生在塔楼上的问题,也就是我住过的地方,我称之为垂直士绅化。在高层建筑的顶层,富豪、亿万富翁、寡头购买公寓,并将其中的两到三套组合在一起。在实践中,它导致了在顶层的永久建筑工地。如果你住在一栋由巨大的钢筋混凝土制成的大楼里,你会听到一个勺子从30楼一直掉到地下室的声音。鉴于此,想象一下建筑工人整天钻孔、拆除钢筋混凝土或悬挂吊顶、重修浴室。 特别是在疫情期间,当我们都在家里工作时,那真是地狱。

据我所见,巴比肯繁荣的新居民并不满意其简陋的风格,而是想要更豪华和精致的装饰。更重要的是,尽管这些公寓在当时被认为是相当大的,但浴室被规划的很小,可能是由于那个时代的节俭精神。如今的富裕业主有着不同的品味;因此,浴室正在被改造。

例如,在疫情期间我居住的塔楼里,顶层安装了一个石材切割车间,持续了数月,这就意味着三部电梯中的一部被建筑承包商长期使用,上上下下,运送大理石板。