イリーナ・ダヴィドヴィッチ:ウェブサイトのタイトルは「家は何のためにあるのだろう」ですね。何よりもまず私は、家は人を住まわせるものだと認識しています。一回きりの傑作としての芸術的構想よりも、住宅の大量生産の方に興味があります。標準化され大量生産された住宅は、その時代の社会的価値や願望を物語ってくれるからです。歴史家としては、その生産背景にあるイデオロギーや原型に興味があるのです。ヘンリー・ロバーツによる1851年の四世帯のためのモデル住宅を選んだのもそれが主な理由です。

このプロジェクトは当時としては画期的なものだったのでしょうか?

ロバーツはキャリアをスタートさせた当初は、典型的なヴィクトリアン・アーキテクトでした。つまり社会的な地位としてもゆとりのある建築家として、こっちではマナーハウスを作り、あっちでは教会を作り、といった具合です。初期のプロジェクトの一つに貧窮した船員たちのためのシェルターのプロジェクトがありました。これが後に広がる慈善活動の種となりました。1844年、彼はS.I.C.L.C.(労者階級の状態改善協会)の名誉建築家となりました。この福音主義的良心に基づいた慈善団体は、強力なパトロンをもつ重要な政治的集団でした。この団体の目的は、まず第一に大衆へ向けた住宅モデルを開発し普及させること。そして次に、労働者のための手頃な住宅モデルをテーマとした知見を生産し収集し交換することでした。S.I.C.L.C.での活動を通して、ロバーツは建築家にとっての新しいテーマを専門知識として身につけたのです。

今日、議論するモデル住宅は、過密なスラム街で生じる危険、つまり新しい都市生活者としての労働者の身体的、道徳的健康に対する解決策として開発されたものです。おそらく、その裏に隠された道徳的意図の方がより重要だったのだと思われます。この家はブルジョワジー(資本家としての)と同じ道徳的価値観に従うように促すことで、労働者階級を統制する方法としてのモデルを示していたわけです。その計画は、社会工学の一種として理解することができるでしょうか。素晴らしいエッセイがありますよね。ロビン・エヴァンスの

「貧民窟とモデル住宅」です。そこでは、この考え方について触れられています。(「貧民窟とモデル住宅」: イギリスの住居改革とプライベートスペースの倫理 , AAファイル ,Vol: 10 No.1 1978)

この住宅は、革命的なものだったのか?短絡的に答えればイエスでしょう。大衆住宅の問題に答えた初めてのものであり、おそらく、都市の秩序を表現する試みとして捉えることもできるでしょう。ご存知のように、この住宅はモデル住宅、つまりプロトタイプなわけです。何十万もの来場者がいた1851年のロンドン万国博覧会に出展され、世界中の人々が大きな関心を寄せました。本格的なものだったのです - 単なる計画ではなく、施工方法、コスト、さらには契約方法まで考えられたものでした。当時の市場で流通していた方法と比べると施工面において、より安く軽く作れるものとして(中空レンガを使った耐火構造によるもので、ヘンリー・ロバーツは特許を取得していました。)都合も良く安全性も高いものでした。さまざまなレベルにおいて革新的なプロジェクトとして、開発者の興味を引き、大量に生産されることが意図されていました。労働者の生活環境の根本的改善は、街全体の衛生状態に影響を及ぼすと考えられていました。ですからプロジェクトは非常に著名な人々からの後ろ盾があったのです。万国博覧会に出展されることになったのもアルバート公の仲介があったからです。非常にクレバーなやり方でした。だからこそ世界中から何千もの人々が訪れ、目にすることができたのです。プロジェクトは非常にベーシックなものでした。そのシンプルさゆえに極めて複製しやすいものです。今日の住宅にも、その子孫を見ることができます。

もう一つ革命的であったことは、大きな社会的問題であった住宅生産に対しての建築家の役割を変えたということです。ロバーツのキャリアは、住宅の専門家としての建築家の出現を物語っています。彼は、プロトタイプの開発と並行して、論文でもあり、建設カタログでもあり、建築マニュアルである『勤労者階級の住宅』(1850)を執筆しています。これがいかにして他国においてのモデルとなったかを示す一例として、フランス語訳の経緯をお話ししましょう。ナポレオン3世は1850年にロンドンに滞在していました。彼は改革に大変興味を持っていました - ご存知のように - 都市の公共事業のことです。この本への熱意は、翻訳版をフランスの全自治体に配布するよう命じるほどでした。実際、フランスの全自治体がこのマニュアルのコピーを保有していました。ジャン・ドルフュスが1853 - 54年に建設したミュルーズにある有名なシテ・オヴリエール(労働者村)はロバーツのプロトタイプをもとにしたものです。(Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie)

複製に関して言えば、ロバーツのモデルハウスはそれぞれが独立したユニットをもつ四世帯のための一つの建物を想定しているわけですが、この数字が重要なのでしょうか?

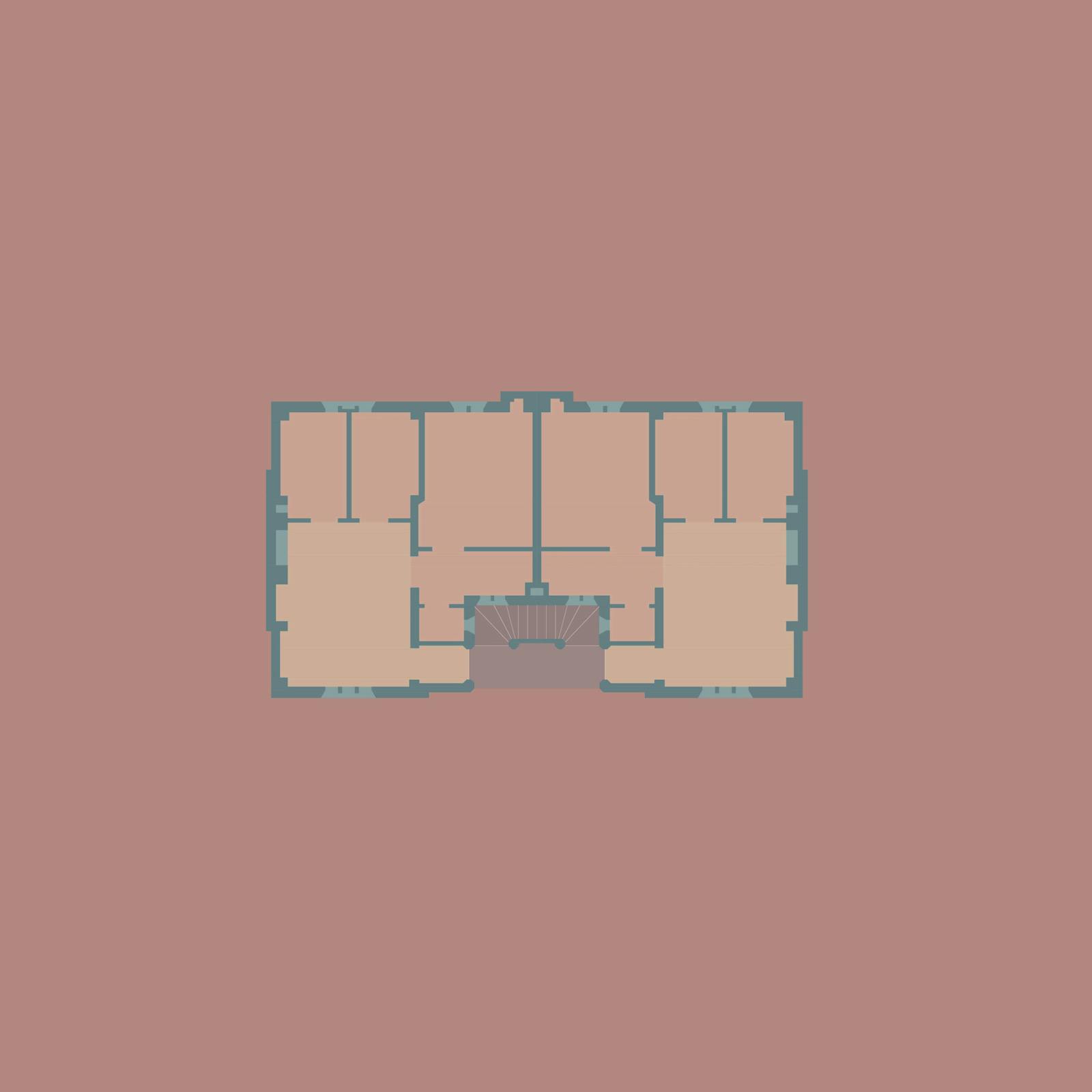

そうではないと思います。私はこのプロトタイプをある断片と捉えています - さまざまな方法で複製され、構成されることが意図されたものとして。ロンドンにはビルダーも起業家もいましたから。特にシドニー・ウォーターロー。彼は、このモデルをもとにいくつかの長屋を開発しています。そのファサードを見ると、プロトタイプを一つのモジュールとして、水平にも垂直にも増殖していく様子がよくわかります。その点では、4という数字が全く重要というわけではなく、8でも16でも良いのです。いや2でもいいのかもしれませんが。実際のところ、この計画は二種類の住居タイプに分けられるよう考えられていました。一つ目は、標準的なコテージ、つまり二世帯のセミデタッドハウスの原則として。もう一つは、より大きな家、つまり多層階、多世帯の住宅の一断片として。ベーシックな提案であるがゆえに、こういったバリエーションに対応できるというわけです。

彼の著作から判断するに、ロバーツはシステマティックでプラグマティックな人物なのだと想像します。もちろん、理想的には労働者も自分の庭をもてるようなコテージに住むべきだ、と彼は言うわけですが。しかし、都心における土地の希少性やコストの問題のために別の解決策が推し進められたのです。複数の家族を複数のフロアで収容するという解決策です。原型となったのは、二階建ての建物です。はっきり言ってしまえば、何もないのです。勾配屋根のないコテージ。いや不完全なアパートといった感じでしょうか。19世紀には、とても奇妙に映ったことでしょうね。今見ても変だと思いますから。

ニッチ(ファサードにある)は、社交の場となることが意図されていたのでしょうか?

残念ながらヘンリー・ロバーツが何を考えていたのか、彼の著作以上のことはわかりません。私たちがそのイメージに近づきすぎてしまい、現代的な価値観を投影してしまうことは危険ですね。自覚すべきことは、ニッチが都市的なジェスチャーなのか、出会いのための空間なのか、といった問いからは距離を保つことです。

そのニッチは興味深い空間ですよ。なぜなら実際は、出会いを最小化するための空間だからです。当時は、家庭内の妻が、他の家庭の男性と監視されていない空間で出会うことは問題視されていました。その考えの根底には、もちろん公衆衛生的観点、つまり病気の蔓延を避けるために、家族同士を分離したり、共有空間の自然換気をすることが必要とされていました。複数の人が行き来することになる長い廊下をなくしてしまうことで、問題が発生する可能性を減らすことができたのです。家庭内のプライバシーが重要視されていましたし、家同士はできるだけ離す必要がありました。さて、このニッチが都市に対するジェスチャーであるかどうかですよね。疑わしいですね。彼の本には都市計画に関することは、ほとんど書かれていないのです。

建築家が社会主義的な思想に染まり、労働者に社会的流動性を促すことを本気で考えるようになったのも、この計画の少し後のことで、19世紀末のことです。19世紀半ばであったこの当時は、ただ病気を防ぐことだけが望まれていました。つまり、ニッチは空間と風通しのためにあるものでした。現実的で残念な感じはありますが、病気へのリスクを最小限に抑えるためだけのもの、ということです。

ニッチには屋根がついていますが、空気の循環のためにも開放されています。ジョン・スノウによってコレラの理論が実証される数年前まで、コレラは空気感染するもので、悪臭(瘴気)を通じて伝染すると考えられていました。換気の必要性は、当時の改革派の建築家たちのこだわりだったのです。労働者階級の人々もわかってはいましたが、多くが逆の方向へ向かってしまいました。

このような場所の住人は、隙間風を嫌い、家が冷え込むのを防ぐためなら何でもするだろうと思われていたのです。建築家たちは、住人が家を密閉するのをいかに阻止するか、公然と議論をしていました。ニッチならば開放されていて、布切れで詰めて塞ぐことなどできません。このニッチは、共用部の換気を確保するための現実的な方法でした - 今日、私たちがとても敏感になっている話題ですね。

このプロトタイプは、モダニズムの前兆だと言えるでしょうか?

もちろん。そういう意味でとても興味深く見ているのです。フラットルーフは私たちにとっては見慣れたものですが - 未完成のプロジェクトとして、量産化され完成されるのを待っていることを示す手法でもあるのです。勾配屋根をかけて従来のコテージにするのか、あるいは増殖させることで多層の長屋にするのか、どちらかの方法によって完成するプロジェクトなのです。

モダニズムの集合住宅、例えばエルンスト・マイの『ニュー・フランクフルト計画』はとりわけ、モデル住宅を、中央のニッチを含めて4、5階まで押し出したような外観に見えるのです。

そう見えるのは、禁欲的で、反復的で、工場生産的に見えるよう仕組まれたモダニズムの美学のせいだけではないでしょう。二つの住居の開口部が、共通動線としてのコアの二面に面しているという、本当の意味で過不足のないプランの実利性によるものでもあるでしょう。この構成に一度気づいてしまうと、あらゆる住宅に同じ構成があることにも気づくはずです。それが、とても合理的で経済的だからです。ロバーツはこの構成を発明したわけではなく、スコットランドの古い長屋から記録していたのです。ただ、この構成を使い続け、文章にした建築家としては、彼が最初の建築家であることは、間違いないでしょう。

このモデル住宅は、さまざまな場所に、つまり職場からの距離にかかわらず、どこにでも設置できるわけですが、都心の良くない環境の中では結局、不快感を感じてしまうのではないかと思われます。モデル住宅にそれを補うような生活の質があるとすれば、それはどういうものでしょうか?

ロバーツのモデル住宅は、それが使用される状況や設置場所、それに都市環境への影響に対しては全く関心を示していません。快適性や生活の質といった考え - それらは全く無意味なことなのでしょう。重要なのは、このプロトタイプがたいていの都市において実現可能な - そして実際に実現されている - ことなのです。建築家の関心は内 - 向きなもので、たいていは個々の住居、特にプランに向けられていました。外壁面は主に、内部での現象や住居間の関係性の結果であり、ファサードは、ただプランの原理が反映されたものとして、そこに多少の飾り付けがあろうが無かろうがどちらでも良いのです。

これは、18世紀から19世紀にかけてロンドンやバース、ダブリンなどに建てられた投機的なジョージアン様式のテラスハウスとは全く異なるものです。標準化され高度に類型化されたものとしては同じですが、根底にある考えが根本的に違っていて - ファサードは住人の社会的、経済的地位を反映する礼儀の一つなのです。

ファサードは住人のステータス(時には誤解を招くことももちろんあるのですが)を外の世界へ伝えるために成文化されたものでした。つまり立面図に焦点が当てられていました。一方、モデル住宅は、新しい社会階層である都市労働者の生活習慣を正すことに焦点が当てられていました - つまり平面図が重要だというわけです。

ロバーツの思想が生まれる前には、労働者階級 - 彼らが都市の貧困層の大部分であるわけですが - の間ではプライベートとパブリックといった概念はほとんど無意味なものでした。(フリードリヒ)エンゲルスは、セント・ジャイルズの貧困窟のことを、玄関がなく盗む物も何もない無法地帯だと表現しています。スラム街は、このように、奇妙で倒錯的で、それに命の危険性さえある場所として共通していました。住人の一部は、スラム街の隅々まで入り込むようにして生活していましたし、良くも悪くも、そこにはある種のコモンセンスが生まれていたのです。ですから、たいていの場合、新しいモデル住宅はスラムの住人にとってそんなに良くは思われていませんでした。彼らは、意固地な自由さと引き換えに、屈託のない心地良さを手にする、という考えに慣れる必要がありました。

ヴィクトリア朝は、意欲的な中流階級の価値観や、住民の道徳心を前提としたさまざまなタイプの住宅を取り入れました。そこでの戦略は、分離、分離、分離 - つまりほとんどが分割と統治の原則を応用したものでした。ロビン・エバンスによれば、ロバーツのプロトタイプは、家族には住居を、個人には部屋を供給するという分離を行ったものでした。世代、性別、家族をそれぞれ別にすることで生じてくるのは基本的にプライバシーの問題です。多くの労働者にとっては、プライバシーとは、おそらくこのような住居で初めて明示されたものなのです。彼らの多くは田舎からの貧しい移民でしたし、家の外部と内部との領域の関係に対する考えは、全く違っていました。つまり、住居は新しい都市市民を作り出すための装置であり、産業社会の基礎を作るものだったのです。

実際問題として、このような住居は、中流階級以下の職人や事務員などの定期賃金があり、家賃を毎月支払う余裕のある人々に適したものであることが証明されてしまったわけですが。事実として、改革住宅は、社会の中で最も弱い立場の人々のためとはならなかったのです。

快適さという概念は、この際、余計なものでした。ひどい環境で暮らしてきた人々が突然、光や空気、個室にシンク、それにトイレを手に入れたら喜ぶだろう、と普通そう思いますよね。インフラとしても、この提案は時代を先取りしたものでした。ロバートのビジョンは、こういった人々がシンクやトイレの使い方を知っていることを前提としていました。パリでは1912年の時点においても、建築家たちが計画していた貧困層のための最小限住宅は共同浴槽でした。なぜなら、個人の浴室が綺麗に使われるとは考えていなかったからです。ロンドンでは、19世紀の労働者住宅 - 例えばピーボディ・トラスト - の多くは、第二次世界大戦後になってようやく浴室がつくようになったのです。

労働者階級のための建物を、古典建築の原則によって高貴なものにしようとする意図があったのでしょうか?強いシンメトリーは、形式的にかの名高いパラッツォのイメージと似ていると感じるのですが。

まさに。そうなんです。パラッツォ的なイメージは、多層階になった時に強く表れていますね。大博覧会の時のプロトタイプにはそれほど表れてはいないですが。新しい存在としてのこの住宅に、威厳を与えようという意図があったのだと思います。パラッツォ的表現が多層階の住居と結びつき、ある種の形態学にモニュメンタリティが与えられたのです。

ファサードの構成に関してはどう思われますか?このモデル住宅の他の価値と比べれば、無視しても良いようなものですか?

モデル住宅の外観は魅力的ですよ。当時もそうですし、今見てもかなり異様ですね。すごい不細工ですよね。プロポーション的に。先に述べたように、このプロポーションが示しているのは、このモデル住宅が何らかの形で選択され、適応され、改善される可能性なのだと思います。ファサードの未完成性を公然と見せつけている建物。ともかく完成させてくれと訴えかけているようです。モデル住宅としての、ある状況を示しているのでしょう。本物としてではなく。

2022年01月10日

Irina Davidovici: The title of your website is „what is a house for”. Primarily, as far as I am concerned, a house is for housing people. I’m more interested in the mass production of houses than their artistic conception as one-off masterpieces. Standardised and mass-produced houses tell us about the values and aspirations of society at any given time. And as a historian, I am interested in the origin and underlying ideologies behind their production. This was my main motivation for choosing the Model Houses for Four Families by Henry Roberts from 1851.

WAS THIS PROJECT REVOLUTIONARY AT THE TIME?

At the beginning of his career Roberts was a typical Victorian architect: of comfortable social standing, doing a manor house here, a church there. One of his early projects was a shelter for destitute sailors, which became the seed for more philanthropic works. In 1844, he became Honorary Architect to the Society for Improving the Conditions of the Labouring Classes (S.I.C.L.C.), a charitable society animated by evangelical conscience and a significant political player, with patrons in the highest places. This society aimed, firstly, to develop and promote housing models for the mass market. Secondly, it sought to produce, collect and exchange knowledge on the topic of affordable housing for labourers. Through his work for S.I.C.L.C., Roberts gained expertise on what was an emerging topic for architects.

The model house we discuss today was developed as a solution to the dangers brought about by overcrowded slums, the threats they brought to the bodily and moral health of the new urban dweller, the labourer. Possibly, the hidden moral agenda was the more important. This house offered a model of how to control the working classes, by encouraging them to adhere to the same set of moral values as the (capitalist) bourgeoisie. Its planning can be seen as a manner of social engineering. There’s a wonderful essay, ‘Rookeries and Model Dwellings’ by Robin Evans that deals with this idea. („Rookeries and Model Dwelling: English Housing Reform and the Moralities of Private Space’, Robin Evans, AA Files, Vol: 10 No.1 1978).

Was the house revolutionary? The short answer is yes. We are tempted to see it as the first house that responded to the question of mass housing, perhaps even the expression of an attempt to bring about urban order. As you know, it’s a model house, a prototype. It was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, visited by hundreds of thousands of people, and as such it elicited a huge amount of interest from an extended international audience. It was a true product – not only in terms of planning but also methods of construction, even the costs and residential contracts were worked out. It was cheaper and lighter to construct (Henry Roberts patented a type of fireproof construction with hollow bricks), more expedient, safer than what was at that time available on the market. It was an innovative project at several levels, meant to interest developers and be produced en masse. What was seen as a radical improvement of living conditions of workers was also to affect the hygienic condition of the entire city. So the project was backed by very prominent people. It was included in the Great Exhibition at the personal intervention of Prince Albert. This was a very clever move, for in this way the prototype was visited by thousands of people from all over the world. It was very basic and on account of its simplicity eminently replicable. We see its progeny in housing even today.

Something else I see as a revolutionary development was that it changed the role of architects in relation to the production of housing, eminently a social matter. Roberts’s career marks the emergence of the architect as housing expert. In parallel with the prototype he wrote the part-treatise, part constructional catalogue, part-building manual ‘The Dwellings of the Labouring Classes’ (1850). One example of how this eventually became a model for other countries is the story of its French translation. Napoleon III, who was in London in 1850, was very interesting in matters of reform and – as we know – urban public works. He was so enthused that he ordered its translation and had it distributed to all local authorities in France. Every French municipality had a copy of this manual. The famous cite ouvrière (workers’ village) in Mulhouse, built by Jean Dollfus in 1853-54, was based on Roberts’s prototype (Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie).

WHEN IT COMES TO BEING REPLICATED, THE MODEL HOUSE BY ROBERTS PROPOSES ONE BUILDING FOR FOUR FAMILIES, EACH IN ITS OWN SEPARATE UNIT. IS THIS NUMBER IMPORTANT?

Not really. I see this prototype as a fragment - a piece of code, meant to be replicated and composed in very different ways. There were builders and entrepreneurs in London, particularly Sydney Waterlow, who developed several tenement blocks based on this model. The facades show clearly how the prototype was used as a module and multiplied both vertically and horizontally. In that respect, the number four was not at all important: it could have been eight or sixteen. Or, indeed two. In fact, the scheme was intended to be declinated into two different types of dwellings. One possibility was to use it as the basis for standard cottages, semi-detached houses for two families. In the other scenario, it could be a fragment of a much bigger house, a multi-story, multi-family house. It is such a basic proposal that it lends itself to all these variants.

Based on his writings, I imagine Roberts as a systematic and pragmatic man. He said, of course, ideally, workers should live in cottages with their own garden. But in the city, the scarcity and the high cost of ground pushed for a different solution, housing multiple families on several floors. The original prototype, the two-stories building, was nothing if not a compromise: a cottage without its pitched roof, an incomplete block of flats. In the 19th century, it would have appeared very weird to people. I think it still looks weird.

WAS THE NICHE (ON THE FAÇADE) MEANT TO BE AN ARTICULATED SPACE OF SOCIAL INTERACTION?

Unfortunately, we don’t know what Henry Roberts’s thought beyond what he wrote. The danger is that we get attached to the images and get compelled to project our own, contemporary values onto them. We must be very aware of that and create a distance from questions such as whether this was an urban gesture, or a space of encounter.

The niche you refer to is interesting because it is a space that’s meant to actually minimise encounter. At this point in time, it was seen as problematic that, say, the wife of one family could meet the man of another family in a space where they’re unsupervised. Its underlying reason was of course public health, namely the need to separate families in order to avoid the spread of disease, and naturally ventilate the shared spaces. Getting rid of a long corridor, where several people can meet, is a way of minimising potentially problematic encounters. There was a lot of emphasis on domestic privacy, so the houses needed to be separated from each other as much as possible. And in terms of whether this is a gesture towards the city, I very much doubt that it was meant in that way. The book has very little to say on questions of urban planning.

It was only later, towards the end of the 19th century, that architects were imbued with socialist ideas that really wanted to offer social mobility to the workers. But at this point in the middle of the 19th century, they just didn’t want people to get sick. So, the niche was about space and ventilation. Pragmatically, perhaps disappointingly so, it was really about minimising the risk of disease.

The niche was covered, but open to air circulation. A few years before the theory of cholera was demonstrated by John Snow, people still thought that cholera was just airborne and transmitted through bad smells (miasma). The need for ventilation was an obsession of reforming architects of the time. It also became an obsession for the working classes, but mostly in the opposite direction.

People who lived in these places were seen as hating draughts and doing everything they could to prevent their houses from getting colder. Architects discussed openly how to stop the inhabitants from sealing off their homes. The niche was open: you could not stuff it closed with some rags. It was a pragmatic way of ensuring that the common areas would remain ventilated – something we have ourselves become very attuned to nowadays.

WOULD YOU SAY THIS PROTOTYPE IS A HARBINGER OF MODERNISM?

Absolutely. I’m very interested in seeing it like that. The flat roof looks familiar to us – but it was really a way of showing that the prototype was an unfinished project, awaiting completion through mass production. It’s a project that will achieve completion, either through the addition of a pitched roof, in which case it becomes a conventional cottage, or through multiplication, in which case it becomes a multi-story tenement.

Some modernist mass housing, for example Ernst May’s Neue Frankfurt Siedlungen, looks strikingly like a Model House extruded to four to five floors, including the central niche.

That’s not only because of the modernist aesthetic, programmed to look ascetic, repetitive, and factory-made. But also because of the genuine, faultless pragmatism of the plans, with two dwellings opening on two sides of the common circulation core. Once you recognize this configuration you see it everywhere in housing, because it is so rational and economical. Roberts did not invent this configuration, which he had documented in older Scottish tenements. Still, he was almost certainly the first architect to employ it in a consistent manner, and to also write about it.

THIS MODEL HOUSE CAN BE PUT IN DIFFERENT LOCATIONS, AT VARIOUS DISTANCES FROM THE WORKPLACE.

WHAT IS THE LIVING QUALITY THAT COMPENSATES THE EVENTUAL DISCOMFORT GIVEN BY A LESS FAVOURABLE POSITION IN THE CITY?

The Roberts Model Houses display no interest whatsoever towards the context of their use, their location, or their impact on the urban environment. Notions of comfort, of life quality – all these are a moot point. The point is that this prototype can – and actually does – occur almost anywhere in the city. The architect’s focus was inward-looking, mostly on the individual dwelling, and particularly on its plan. The outer shell is mainly the consequence of what happens on the inside and the relation between these dwellings. The façade is a default of the plan, give or take a couple of flourishes.

This is very different from say the speculative Georgian terrace houses built in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries London, Bath, Dublin and so forth. Although they were also standardised and in fact highly typified, the underlying assumption was fundamentally different – one of decorum, of reflecting the inhabitants’ social and economic position.

The facades were codified to communicate to the outer world the status of their residents (sometimes misleadingly, of course): the focus was on elevations to tell the story. Whereas in the Model Houses, the focus was on correcting the domestic habits of a new social class, the urban labourer – and thus, on the plan.

At the time before the ideas of Roberts came to being, the notions of private and public among the members of working class – and the urban poor, which to a great extent they represented – were almost irrelevant. (Friedrich) Engels described St Giles’ Rookery as a lawless place, where “there are no front doors, there being nothing left to steal”. The slum carried within it this kind of strange, perverse, even life-threatening, form of commonality. But a certain type of slum dweller flourished in these nooks and crannies, in places where they could scurry into. Besides, a certain commonality came out of it, whether good or bad. So, in many cases, in many situations, the new model houses were not very popular among slum dwellers. They had to get used to the idea that they were trading a perversely understood freedom for obvious comfort.

Victorians introduced a different type of housing, based on aspirational middle-class values, and on the assumption of the inhabitants’ moral fibre. Their strategy was to separate, separate, separate - almost an application of the divide and rule principle. As Robin Evans said, Roberts’s prototype compartmentalised families to own dwellings and individuals to own rooms. You set apart the generations, the sexes, families from each other, you create what is basically a privacy problematic. For many workers, privacy was perhaps articulated for the first time in this kind of dwellings. Most of them were very poor immigrants from the countryside, where again, there’s a very different set of territories between the exterior and the interior of the house. So, the dwelling became an apparatus for creating a new urban citizen, the building block for the industrial society.

In practice, these dwellings proved to be better suited to the lower middle classes, artisans and clerks, people with regular wages who could always afford to pay rent. In fact, reform housing did not really cater for the most vulnerable members of society.

The idea of comfort was superfluous to all this. One would think that people who had lived in terrible conditions would be happy to suddenly have light, air, rooms, a sink and a toilet. Infrastructurally, this proposal was way ahead of its time. Roberts’s vision assumed that these people knew how to use a sink and a toilet, for that matter. In Paris, as late as 1912, architects were still planning a type of basic housing for the poor with communal bathrooms, because people were deemed incapable of using and cleaning their own bathrooms. In London, much of the nineteenth-century worker’s housing – the blocks of the Peabody Trust for example – were only fitted with bathrooms after World War Two.

WAS THERE AN INTENTION TO GIVE TO A BUILDING, BUILT FOR WORKING CLASS, A MORE NOBLE CONSTRUCTION, DRIVEN BY RULES OF CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE? THE STRONG SYMMETRY RESEMBLES A FORMALLY ACCEPTED IMAGE OF A PALAZZO.

Oh yes. The palazzo’s image is very much present in the multi-story version, if not that much in the Great Exhibition prototype. There was an intention to give dignity to this housing, to this new type of existence. The palazzo expression was tied into multi-story dwellings. It bestowed monumentality upon a certain morphology.

WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE COMPOSITION OF THE FACADE, IS IT SOMETHING THAT YOU IGNORE CONSIDERING ALL THE OTHER VALUES?

The appearance of the Model Houses fascinates me, but it fascinates me because it’s so alien, in the context of both its time and our time. It’s quite ugly, I think, in its proportions. As I mentioned already, these proportions were meant to be adopted, adapted, ameliorated one way or another. It’s a building that openly shows its incompleteness on the facade. It almost asks for it to be finished somehow else. I think it is intended to show its condition of a model house, and not a real one.

10.01.2022

伊琳娜-达维多维奇:你网站的标题是 "住宅所为何"。首先,就我而言,住宅是用来住人的。我对住宅的大规模生产更感兴趣,而不是它们作为独一无二的杰作的艺术性概念。标准化和大规模生产的住宅告诉我们在任一特定时期的社会的价值和愿望。作为一位历史学家,我对这种生产背后的起源和底层的意识形态感兴趣。这是我选择亨利-罗伯茨1851年创作的《四个家庭的样板房》的主要动机。

这个项目在当时是革命性的吗?

在他职业生涯的初期,罗伯茨是一个典型的维多利亚时代的建筑师:拥有舒适的社会地位,这儿做一个庄园,那儿做一个教堂。他的早期项目之一是贫困水手的庇护所,这成为更多慈善事业的种子。1844年,他成为改善工人阶级状况协会(S.I.C.L.C.)的名誉建筑师,这是一个由福音派良心驱动的慈善协会,也是一个重要的政治参与组织,其赞助人都是最高层人士。该协会的目标是,首先,为大众市场开发和推广样板房。其次,它试图生产、收集和交换关于工人可负担的住房的知识。通过他在S.I.C.L.C.的工作,罗伯茨获得了这些建筑师新兴话题的专业知识。

我们今天讨论的样板房是为了解决过度拥挤的贫民窟带来的危害,以及它们对城市的新居民——工人的身体和道德健康带来的威胁。或许,隐含的道德议程更为重要。这栋住宅提供了一种如何控制工人阶级的模式,既鼓励他们遵循与(资本主义)资产阶级相同的道德价值观。它的计划可以被看作是一种社会工程的方式。罗宾-埃文斯(Robin Evans)有一篇精彩的文章,《贫民窟与样板住房》(Rookeries and Model Dwellings),涉及到这个想法。(贫民窟与样板住房: 英国住房改革和私人空间的道德观,罗宾-埃文斯,AA档案,第10卷第1期,1978年)。

这座住宅是革命性的吗?简短的回答是肯定的。我们试图将它看作是第一座回应大众住房问题的住宅,甚至可能是尝试实现城市秩序的表达。如你所知,它是一种样板房,一种原型。它在1851年伦敦的万国博览会上展出,获得了成千上万人的参观,因此引起了广大国际观众的巨大兴趣。它真正的是一个产品——不仅在计划方面,也在施工方式上,甚至连造价和住宅合同都制定了。它的建造成本更低,重量更轻(亨利-罗伯茨获得了空心砖的防火建筑专利),比当时市场上的产品更方便和安全。这是一个在多个层面上创新的项目,旨在引起开发商的兴趣并进行大规模的生产。这个被视为从根本上改善工人生活条件的项目也将影响整个城市的卫生状况。因此,该项目得到了非常知名的人士的支持。在阿尔伯特亲王的亲自干预下,该项目被纳入了万博会。这是一个非常聪明的举动,这样一来,来自世界各地的成千上万的人参观了这个原型。它是非常基本的,并且由于其简单性而具有明显的可复制性。即使在今天,我们也能在住宅中看到它的后代。

我认为另一个革命性的发展是,它改变了建筑师在住宅生产方面的角色,这显然是一个社会问题。罗伯茨的职业生涯标志着出现了建筑师作为住宅专家的情况。在创作原型的同时,他写了一些论述、一些建筑目录、一些建筑手册《劳动阶级的住宅》(1850)。这本书最终成为其他国家的典范,其中一个例子是其法文翻译的故事。1850年在伦敦的拿破仑三世对改革——如我们所知——与城市公共工程事宜非常感兴趣。他非常兴奋,下令翻译该书,并将其分发给法国的所有地方当局。每个法国城市都有一本该手册的副本。让-多尔福斯(Jean Dollfus)于1853-54年在穆尔豪斯(Mulhouse)建造的著名的工人村(cite ouvrière),就是以罗伯茨的原型为基础的(Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie)。

当涉及到复制时,罗伯茨的样板房提议为四个家庭建造一栋楼,每个家庭都有自己的独立单元。这个数字重要吗?

其实并不重要。我把这个原型看作是一个片段——一段代码,旨在以非常不同的方式进行复制和组合。在伦敦有一些建筑商和企业家,特别是悉尼-沃特洛(Sydney Waterlow),他们在这个模型的基础上开发了几个住宅区。它们的立面清晰地展示了原型是如何被用作模块,并在垂直和水平方向上复制的。在这方面,4这个数字一点都不重要:它可以是8或16。或者,其实是2。事实上,该方案旨在分解为两种不同类型的住宅。一种可能性是将其作为标准平房的基础,即两个家庭的半独立式住宅。而另一种情况下,它可以成为一个更大的住宅的片段,一个多层、多家庭的住宅。这是一个如此基本的提议,它适合于所有这些变体。

根据他的著作,我设想罗伯茨是一个有系统和务实的人。他说,当然,在理想情况下,工人应该住在有自己的花园的平房里。但在城市中,地面的稀缺性和高成本推动了不同的解决方案,将多个家庭安置在几个楼层。最初的原型,即两层楼的建筑,仅仅是一种妥协:没有坡屋顶的平房,一个不完整的公寓楼。在19世纪,人们会觉得它非常奇怪。我认为它现在仍然看起来很怪。

这个壁龛(在外立面上)是为了成为一个社会互动的衔接空间吗?

不幸的是,我们不知道亨利-罗伯特的想法,除了他写的东西。危险的是,我们会依附于这些图像,并不得不将我们自己的、当代的价值观投射到它们身上。我们必须非常清楚这一点,并与诸如这是一个回应城市的姿态,还是一个相遇的空间这样的问题建立一段距离。

你提到的壁龛很有趣,因为它实际上是一个旨在减少接触的空间。在当时那个时间点上,一个家庭的妻子在一个没有监督的空间里和另一个家庭的男人见面,会被认为是有问题的。其根本原因当然是公共卫生,名义上需要将家庭分开,以避免疾病的传播,又有自然通风的共享空间。摆脱长长的走廊,几个人可以在那里见面,这是一种尽量减少潜在问题的相遇方式。有很多人强调家庭隐私,所以需要尽可能地将每户住宅相互分开。而就这是否是对城市的一种姿态而言,我非常怀疑它是否有这样的意图。这本书对城市规划的问题所言甚少。

只是到了后来,即19世纪末,建筑师们才受到社会主义思想的熏陶,真正想为工人们提供社会流动性。但在19世纪中期,他们只是不想让人们生病。因此,壁龛是关于空间和通风的。务实的说,也许令人失望的是,它确实是为了最大限度地减少疾病的风险。

壁龛被覆盖,但对空气流通开放。在约翰-斯诺(John Snow)证明霍乱理论的几年前,人们仍然认为霍乱是通过空气传播的,并且通过不良的气味(瘴气)传播。通风的需要是当时改革派建筑师们的一个心病。它也成为工人阶级的痴迷,但大多是在相反的方向。

住在这些地方的人被视为讨厌通风,并尽一切可能防止他们的住宅变冷。建筑师们公开讨论了如何阻止居民将他们的家封闭起来。壁龛是开放的:你不能用一些破布塞住它。这是一种务实的方式,以确保公共区域保持通风——这也是如今我们自己已经非常适应的事情。

你会说这个原型是现代主义的一个预兆吗?

当然是。我对看到它这样的状况非常感兴趣。平坦的屋顶对我们来说很熟悉——但这其实是一种方式,表明原型是一个未完成的项目,等待着通过大规模生产完成。这是一个将要完成的项目,要么通过增加斜屋顶,成为一个传统的平房,要么通过复制叠加,成为一个多层住宅。

一些现代主义的大规模住房,例如恩斯特-梅(Ernst May)的新法兰克福住区(Neue Frankfurt Siedlungen),看起来非常像一个被拉伸到四到五层的样板房,包括中央的壁龛。

这不仅是因为现代主义的美学,住宅被安排成了禁欲主义的、重复的和工厂制造的样子。还因为计划中真正的、无懈可击的实用主义,两套公寓在共享的交通核的两侧开放。一旦你认识到这种配置,你就会在住宅中处处看到它,因为它是如此经济与合理。罗伯茨并没有发明这种配置,他曾在苏格兰老式住宅中记录过这种配置。不过,他几乎可以肯定是第一个以持续的方式采用这种配置的建筑师,并且还写了下来。

这个样板房可以放在不同的地方,与工作场所保持不同的距离。

城市中不太有利的位置终究会给人带来不适,什么样的生活品质能弥补这种不适?

罗伯茨的样板房没有展示出对其使用语境、位置或城市环境影响的任何兴趣。舒适度和生活品质的概念——所有这些都是没有意义的。关键是,这种原型可以——而且实际上也确实——发生在城市的任何地方。建筑师的重点是内向的,主要是在公寓单体上,特别是在其平面上。表皮主要是内部发生的事情,和公寓间关系的结果。外立面是由平面默认的,或多或少有一些装饰。

这与十八和十九世纪在伦敦、巴斯、都柏林等地投机性建造的乔治亚联排住宅有很大不同。虽然它们也是标准化的,事实上也是高度类型化的,但其潜在的预设是根本不同的——一种礼节,反映居民的社会和经济地位。

外立面的设计是为了向外部世界传达其居民的地位(当然,有时是误导性的):重点是通过立面来讲述故事。而在样板房中,重点是纠正一个新的社会阶层——城市工人——的家庭习惯,因此,重点是平面。

在罗伯茨的想法出现之前,工人阶级成员间的私人和公共概念——以及在很大程度上他们所代表的城市贫民——大抵是无关紧要的。(弗里德里希) 恩格斯将圣客吉勒斯的贫民窟描述为一个无法无天的地方,在那里 “没有前门,没有剩下什么可偷”。贫民窟带有这种奇怪的、反常的、甚至危及生命的共通形式。但某种类型的贫民窟居民在这些角落和缝隙中,在他们可以窜入的地方蓬勃发展。此外,某种共性也由此产生,不管是好是坏。所以在许多情况下,新的样板房在贫民窟居民中不是很受欢迎。他们不得不习惯于这样的想法,即他们正在用一种反常理解的自由来换取明显的舒适。

维多利亚时代的人引入了一种不同类型的住宅,基于令人向往的中产阶级价值观,以及对居民道德品质的假设。他们的策略是分离、分离、分离——几乎是应用分而治之的原则。正如罗宾-埃文斯所说,罗伯茨的原型将家庭分隔到他们的寓所,将个人分隔到自己的房间。你把不同的代际、性别、家庭彼此分开,你创造了一个基本上是隐私的问题。对于许多工人来说,隐私也许是第一次在这种住宅中得到阐述。他们中的大多数人是来自农村的非常贫穷的移民,在那里,住宅的外部和内部之间有一套非常不同的领域。因此,住宅成为创造新的城市公民的工具,成为工业社会的基石。

在实践中,这些住宅被证明更适合于中下层阶级、工匠和文员,这些人有固定的工资,总是能够支付得起租金。事实上,改革后的住房并没有真正照顾到社会中最脆弱的成员。

舒适的想法对这一切属于多此一举。人们会认为,生活在恶劣条件下的人们会很高兴突然有了采光、空气、房间、水槽和厕所。在基础设施方面,这个建议远远领先于它的时代。对于这个问题,罗伯茨的设想里假定这些人知道如何使用水槽和马桶。在巴黎,直到1912年,建筑师们仍然在为穷人规划一种带有公共浴室的基本住房,因为这些人们被认为没有能力使用和清洁自己的浴室。在伦敦,许多19世纪的工人住房——例如皮博迪信托公司的街区——在第二次世界大战后才配备了浴室。

是否有意为工人阶级建造的房子给予一个更高贵的构筑物,并以古典建筑的规则驱使?强烈的对称性类似于一个形式上的府邸形象。

哦,是的。如果说在万博会上的原型中看不到那么多的话,府邸的形象在多层的版本中非常明显。有一个意图是给这种住宅,给这种新型的存在带来尊严。府邸的表达方式与多层住宅联系在一起。它赋予了某种形态学上的纪念性。

你怎么看外立面的构成,它是你考虑到所有其他的价值而去忽略的东西吗?

样板房的外观让我着迷,但它让我着迷是因为它是如此陌生,在它的时代和我们的时代背景下。我认为,它的比例相当丑陋。正如我已经提到的,这些比例是为了被采用,被调整,和被改善的。这是一个在立面上公开显示其不完整性的建筑。它几乎要求以某种其他方式完成。我认为它的目的是要显示它作为一个样板房的状况,而不是一个真实的住宅。

2022年01月10日

イリーナ・ダヴィドヴィッチ:ウェブサイトのタイトルは「家は何のためにあるのだろう」ですね。何よりもまず私は、家は人を住まわせるものだと認識しています。一回きりの傑作としての芸術的構想よりも、住宅の大量生産の方に興味があります。標準化され大量生産された住宅は、その時代の社会的価値や願望を物語ってくれるからです。歴史家としては、その生産背景にあるイデオロギーや原型に興味があるのです。ヘンリー・ロバーツによる1851年の四世帯のためのモデル住宅を選んだのもそれが主な理由です。

このプロジェクトは当時としては画期的なものだったのでしょうか?

ロバーツはキャリアをスタートさせた当初は、典型的なヴィクトリアン・アーキテクトでした。つまり社会的な地位としてもゆとりのある建築家として、こっちではマナーハウスを作り、あっちでは教会を作り、といった具合です。初期のプロジェクトの一つに貧窮した船員たちのためのシェルターのプロジェクトがありました。これが後に広がる慈善活動の種となりました。1844年、彼はS.I.C.L.C.(労者階級の状態改善協会)の名誉建築家となりました。この福音主義的良心に基づいた慈善団体は、強力なパトロンをもつ重要な政治的集団でした。この団体の目的は、まず第一に大衆へ向けた住宅モデルを開発し普及させること。そして次に、労働者のための手頃な住宅モデルをテーマとした知見を生産し収集し交換することでした。S.I.C.L.C.での活動を通して、ロバーツは建築家にとっての新しいテーマを専門知識として身につけたのです。

今日、議論するモデル住宅は、過密なスラム街で生じる危険、つまり新しい都市生活者としての労働者の身体的、道徳的健康に対する解決策として開発されたものです。おそらく、その裏に隠された道徳的意図の方がより重要だったのだと思われます。この家はブルジョワジー(資本家としての)と同じ道徳的価値観に従うように促すことで、労働者階級を統制する方法としてのモデルを示していたわけです。その計画は、社会工学の一種として理解することができるでしょうか。素晴らしいエッセイがありますよね。ロビン・エヴァンスの

「貧民窟とモデル住宅」です。そこでは、この考え方について触れられています。(「貧民窟とモデル住宅」: イギリスの住居改革とプライベートスペースの倫理 , AAファイル ,Vol: 10 No.1 1978)

この住宅は、革命的なものだったのか?短絡的に答えればイエスでしょう。大衆住宅の問題に答えた初めてのものであり、おそらく、都市の秩序を表現する試みとして捉えることもできるでしょう。ご存知のように、この住宅はモデル住宅、つまりプロトタイプなわけです。何十万もの来場者がいた1851年のロンドン万国博覧会に出展され、世界中の人々が大きな関心を寄せました。本格的なものだったのです - 単なる計画ではなく、施工方法、コスト、さらには契約方法まで考えられたものでした。当時の市場で流通していた方法と比べると施工面において、より安く軽く作れるものとして(中空レンガを使った耐火構造によるもので、ヘンリー・ロバーツは特許を取得していました。)都合も良く安全性も高いものでした。さまざまなレベルにおいて革新的なプロジェクトとして、開発者の興味を引き、大量に生産されることが意図されていました。労働者の生活環境の根本的改善は、街全体の衛生状態に影響を及ぼすと考えられていました。ですからプロジェクトは非常に著名な人々からの後ろ盾があったのです。万国博覧会に出展されることになったのもアルバート公の仲介があったからです。非常にクレバーなやり方でした。だからこそ世界中から何千もの人々が訪れ、目にすることができたのです。プロジェクトは非常にベーシックなものでした。そのシンプルさゆえに極めて複製しやすいものです。今日の住宅にも、その子孫を見ることができます。

もう一つ革命的であったことは、大きな社会的問題であった住宅生産に対しての建築家の役割を変えたということです。ロバーツのキャリアは、住宅の専門家としての建築家の出現を物語っています。彼は、プロトタイプの開発と並行して、論文でもあり、建設カタログでもあり、建築マニュアルである『勤労者階級の住宅』(1850)を執筆しています。これがいかにして他国においてのモデルとなったかを示す一例として、フランス語訳の経緯をお話ししましょう。ナポレオン3世は1850年にロンドンに滞在していました。彼は改革に大変興味を持っていました - ご存知のように - 都市の公共事業のことです。この本への熱意は、翻訳版をフランスの全自治体に配布するよう命じるほどでした。実際、フランスの全自治体がこのマニュアルのコピーを保有していました。ジャン・ドルフュスが1853 - 54年に建設したミュルーズにある有名なシテ・オヴリエール(労働者村)はロバーツのプロトタイプをもとにしたものです。(Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie)

複製に関して言えば、ロバーツのモデルハウスはそれぞれが独立したユニットをもつ四世帯のための一つの建物を想定しているわけですが、この数字が重要なのでしょうか?

そうではないと思います。私はこのプロトタイプをある断片と捉えています - さまざまな方法で複製され、構成されることが意図されたものとして。ロンドンにはビルダーも起業家もいましたから。特にシドニー・ウォーターロー。彼は、このモデルをもとにいくつかの長屋を開発しています。そのファサードを見ると、プロトタイプを一つのモジュールとして、水平にも垂直にも増殖していく様子がよくわかります。その点では、4という数字が全く重要というわけではなく、8でも16でも良いのです。いや2でもいいのかもしれませんが。実際のところ、この計画は二種類の住居タイプに分けられるよう考えられていました。一つ目は、標準的なコテージ、つまり二世帯のセミデタッドハウスの原則として。もう一つは、より大きな家、つまり多層階、多世帯の住宅の一断片として。ベーシックな提案であるがゆえに、こういったバリエーションに対応できるというわけです。

彼の著作から判断するに、ロバーツはシステマティックでプラグマティックな人物なのだと想像します。もちろん、理想的には労働者も自分の庭をもてるようなコテージに住むべきだ、と彼は言うわけですが。しかし、都心における土地の希少性やコストの問題のために別の解決策が推し進められたのです。複数の家族を複数のフロアで収容するという解決策です。原型となったのは、二階建ての建物です。はっきり言ってしまえば、何もないのです。勾配屋根のないコテージ。いや不完全なアパートといった感じでしょうか。19世紀には、とても奇妙に映ったことでしょうね。今見ても変だと思いますから。

ニッチ(ファサードにある)は、社交の場となることが意図されていたのでしょうか?

残念ながらヘンリー・ロバーツが何を考えていたのか、彼の著作以上のことはわかりません。私たちがそのイメージに近づきすぎてしまい、現代的な価値観を投影してしまうことは危険ですね。自覚すべきことは、ニッチが都市的なジェスチャーなのか、出会いのための空間なのか、といった問いからは距離を保つことです。

そのニッチは興味深い空間ですよ。なぜなら実際は、出会いを最小化するための空間だからです。当時は、家庭内の妻が、他の家庭の男性と監視されていない空間で出会うことは問題視されていました。その考えの根底には、もちろん公衆衛生的観点、つまり病気の蔓延を避けるために、家族同士を分離したり、共有空間の自然換気をすることが必要とされていました。複数の人が行き来することになる長い廊下をなくしてしまうことで、問題が発生する可能性を減らすことができたのです。家庭内のプライバシーが重要視されていましたし、家同士はできるだけ離す必要がありました。さて、このニッチが都市に対するジェスチャーであるかどうかですよね。疑わしいですね。彼の本には都市計画に関することは、ほとんど書かれていないのです。

建築家が社会主義的な思想に染まり、労働者に社会的流動性を促すことを本気で考えるようになったのも、この計画の少し後のことで、19世紀末のことです。19世紀半ばであったこの当時は、ただ病気を防ぐことだけが望まれていました。つまり、ニッチは空間と風通しのためにあるものでした。現実的で残念な感じはありますが、病気へのリスクを最小限に抑えるためだけのもの、ということです。

ニッチには屋根がついていますが、空気の循環のためにも開放されています。ジョン・スノウによってコレラの理論が実証される数年前まで、コレラは空気感染するもので、悪臭(瘴気)を通じて伝染すると考えられていました。換気の必要性は、当時の改革派の建築家たちのこだわりだったのです。労働者階級の人々もわかってはいましたが、多くが逆の方向へ向かってしまいました。

このような場所の住人は、隙間風を嫌い、家が冷え込むのを防ぐためなら何でもするだろうと思われていたのです。建築家たちは、住人が家を密閉するのをいかに阻止するか、公然と議論をしていました。ニッチならば開放されていて、布切れで詰めて塞ぐことなどできません。このニッチは、共用部の換気を確保するための現実的な方法でした - 今日、私たちがとても敏感になっている話題ですね。

このプロトタイプは、モダニズムの前兆だと言えるでしょうか?

もちろん。そういう意味でとても興味深く見ているのです。フラットルーフは私たちにとっては見慣れたものですが - 未完成のプロジェクトとして、量産化され完成されるのを待っていることを示す手法でもあるのです。勾配屋根をかけて従来のコテージにするのか、あるいは増殖させることで多層の長屋にするのか、どちらかの方法によって完成するプロジェクトなのです。

モダニズムの集合住宅、例えばエルンスト・マイの『ニュー・フランクフルト計画』はとりわけ、モデル住宅を、中央のニッチを含めて4、5階まで押し出したような外観に見えるのです。

そう見えるのは、禁欲的で、反復的で、工場生産的に見えるよう仕組まれたモダニズムの美学のせいだけではないでしょう。二つの住居の開口部が、共通動線としてのコアの二面に面しているという、本当の意味で過不足のないプランの実利性によるものでもあるでしょう。この構成に一度気づいてしまうと、あらゆる住宅に同じ構成があることにも気づくはずです。それが、とても合理的で経済的だからです。ロバーツはこの構成を発明したわけではなく、スコットランドの古い長屋から記録していたのです。ただ、この構成を使い続け、文章にした建築家としては、彼が最初の建築家であることは、間違いないでしょう。

このモデル住宅は、さまざまな場所に、つまり職場からの距離にかかわらず、どこにでも設置できるわけですが、都心の良くない環境の中では結局、不快感を感じてしまうのではないかと思われます。モデル住宅にそれを補うような生活の質があるとすれば、それはどういうものでしょうか?

ロバーツのモデル住宅は、それが使用される状況や設置場所、それに都市環境への影響に対しては全く関心を示していません。快適性や生活の質といった考え - それらは全く無意味なことなのでしょう。重要なのは、このプロトタイプがたいていの都市において実現可能な - そして実際に実現されている - ことなのです。建築家の関心は内 - 向きなもので、たいていは個々の住居、特にプランに向けられていました。外壁面は主に、内部での現象や住居間の関係性の結果であり、ファサードは、ただプランの原理が反映されたものとして、そこに多少の飾り付けがあろうが無かろうがどちらでも良いのです。

これは、18世紀から19世紀にかけてロンドンやバース、ダブリンなどに建てられた投機的なジョージアン様式のテラスハウスとは全く異なるものです。標準化され高度に類型化されたものとしては同じですが、根底にある考えが根本的に違っていて - ファサードは住人の社会的、経済的地位を反映する礼儀の一つなのです。

ファサードは住人のステータス(時には誤解を招くことももちろんあるのですが)を外の世界へ伝えるために成文化されたものでした。つまり立面図に焦点が当てられていました。一方、モデル住宅は、新しい社会階層である都市労働者の生活習慣を正すことに焦点が当てられていました - つまり平面図が重要だというわけです。

ロバーツの思想が生まれる前には、労働者階級 - 彼らが都市の貧困層の大部分であるわけですが - の間ではプライベートとパブリックといった概念はほとんど無意味なものでした。(フリードリヒ)エンゲルスは、セント・ジャイルズの貧困窟のことを、玄関がなく盗む物も何もない無法地帯だと表現しています。スラム街は、このように、奇妙で倒錯的で、それに命の危険性さえある場所として共通していました。住人の一部は、スラム街の隅々まで入り込むようにして生活していましたし、良くも悪くも、そこにはある種のコモンセンスが生まれていたのです。ですから、たいていの場合、新しいモデル住宅はスラムの住人にとってそんなに良くは思われていませんでした。彼らは、意固地な自由さと引き換えに、屈託のない心地良さを手にする、という考えに慣れる必要がありました。

ヴィクトリア朝は、意欲的な中流階級の価値観や、住民の道徳心を前提としたさまざまなタイプの住宅を取り入れました。そこでの戦略は、分離、分離、分離 - つまりほとんどが分割と統治の原則を応用したものでした。ロビン・エバンスによれば、ロバーツのプロトタイプは、家族には住居を、個人には部屋を供給するという分離を行ったものでした。世代、性別、家族をそれぞれ別にすることで生じてくるのは基本的にプライバシーの問題です。多くの労働者にとっては、プライバシーとは、おそらくこのような住居で初めて明示されたものなのです。彼らの多くは田舎からの貧しい移民でしたし、家の外部と内部との領域の関係に対する考えは、全く違っていました。つまり、住居は新しい都市市民を作り出すための装置であり、産業社会の基礎を作るものだったのです。

実際問題として、このような住居は、中流階級以下の職人や事務員などの定期賃金があり、家賃を毎月支払う余裕のある人々に適したものであることが証明されてしまったわけですが。事実として、改革住宅は、社会の中で最も弱い立場の人々のためとはならなかったのです。

快適さという概念は、この際、余計なものでした。ひどい環境で暮らしてきた人々が突然、光や空気、個室にシンク、それにトイレを手に入れたら喜ぶだろう、と普通そう思いますよね。インフラとしても、この提案は時代を先取りしたものでした。ロバートのビジョンは、こういった人々がシンクやトイレの使い方を知っていることを前提としていました。パリでは1912年の時点においても、建築家たちが計画していた貧困層のための最小限住宅は共同浴槽でした。なぜなら、個人の浴室が綺麗に使われるとは考えていなかったからです。ロンドンでは、19世紀の労働者住宅 - 例えばピーボディ・トラスト - の多くは、第二次世界大戦後になってようやく浴室がつくようになったのです。

労働者階級のための建物を、古典建築の原則によって高貴なものにしようとする意図があったのでしょうか?強いシンメトリーは、形式的にかの名高いパラッツォのイメージと似ていると感じるのですが。

まさに。そうなんです。パラッツォ的なイメージは、多層階になった時に強く表れていますね。大博覧会の時のプロトタイプにはそれほど表れてはいないですが。新しい存在としてのこの住宅に、威厳を与えようという意図があったのだと思います。パラッツォ的表現が多層階の住居と結びつき、ある種の形態学にモニュメンタリティが与えられたのです。

ファサードの構成に関してはどう思われますか?このモデル住宅の他の価値と比べれば、無視しても良いようなものですか?

モデル住宅の外観は魅力的ですよ。当時もそうですし、今見てもかなり異様ですね。すごい不細工ですよね。プロポーション的に。先に述べたように、このプロポーションが示しているのは、このモデル住宅が何らかの形で選択され、適応され、改善される可能性なのだと思います。ファサードの未完成性を公然と見せつけている建物。ともかく完成させてくれと訴えかけているようです。モデル住宅としての、ある状況を示しているのでしょう。本物としてではなく。

2022年01月10日

Irina Davidovici: The title of your website is „what is a house for”. Primarily, as far as I am concerned, a house is for housing people. I’m more interested in the mass production of houses than their artistic conception as one-off masterpieces. Standardised and mass-produced houses tell us about the values and aspirations of society at any given time. And as a historian, I am interested in the origin and underlying ideologies behind their production. This was my main motivation for choosing the Model Houses for Four Families by Henry Roberts from 1851.

WAS THIS PROJECT REVOLUTIONARY AT THE TIME?

At the beginning of his career Roberts was a typical Victorian architect: of comfortable social standing, doing a manor house here, a church there. One of his early projects was a shelter for destitute sailors, which became the seed for more philanthropic works. In 1844, he became Honorary Architect to the Society for Improving the Conditions of the Labouring Classes (S.I.C.L.C.), a charitable society animated by evangelical conscience and a significant political player, with patrons in the highest places. This society aimed, firstly, to develop and promote housing models for the mass market. Secondly, it sought to produce, collect and exchange knowledge on the topic of affordable housing for labourers. Through his work for S.I.C.L.C., Roberts gained expertise on what was an emerging topic for architects.

The model house we discuss today was developed as a solution to the dangers brought about by overcrowded slums, the threats they brought to the bodily and moral health of the new urban dweller, the labourer. Possibly, the hidden moral agenda was the more important. This house offered a model of how to control the working classes, by encouraging them to adhere to the same set of moral values as the (capitalist) bourgeoisie. Its planning can be seen as a manner of social engineering. There’s a wonderful essay, ‘Rookeries and Model Dwellings’ by Robin Evans that deals with this idea. („Rookeries and Model Dwelling: English Housing Reform and the Moralities of Private Space’, Robin Evans, AA Files, Vol: 10 No.1 1978).

Was the house revolutionary? The short answer is yes. We are tempted to see it as the first house that responded to the question of mass housing, perhaps even the expression of an attempt to bring about urban order. As you know, it’s a model house, a prototype. It was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, visited by hundreds of thousands of people, and as such it elicited a huge amount of interest from an extended international audience. It was a true product – not only in terms of planning but also methods of construction, even the costs and residential contracts were worked out. It was cheaper and lighter to construct (Henry Roberts patented a type of fireproof construction with hollow bricks), more expedient, safer than what was at that time available on the market. It was an innovative project at several levels, meant to interest developers and be produced en masse. What was seen as a radical improvement of living conditions of workers was also to affect the hygienic condition of the entire city. So the project was backed by very prominent people. It was included in the Great Exhibition at the personal intervention of Prince Albert. This was a very clever move, for in this way the prototype was visited by thousands of people from all over the world. It was very basic and on account of its simplicity eminently replicable. We see its progeny in housing even today.

Something else I see as a revolutionary development was that it changed the role of architects in relation to the production of housing, eminently a social matter. Roberts’s career marks the emergence of the architect as housing expert. In parallel with the prototype he wrote the part-treatise, part constructional catalogue, part-building manual ‘The Dwellings of the Labouring Classes’ (1850). One example of how this eventually became a model for other countries is the story of its French translation. Napoleon III, who was in London in 1850, was very interesting in matters of reform and – as we know – urban public works. He was so enthused that he ordered its translation and had it distributed to all local authorities in France. Every French municipality had a copy of this manual. The famous cite ouvrière (workers’ village) in Mulhouse, built by Jean Dollfus in 1853-54, was based on Roberts’s prototype (Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie).

WHEN IT COMES TO BEING REPLICATED, THE MODEL HOUSE BY ROBERTS PROPOSES ONE BUILDING FOR FOUR FAMILIES, EACH IN ITS OWN SEPARATE UNIT. IS THIS NUMBER IMPORTANT?

Not really. I see this prototype as a fragment - a piece of code, meant to be replicated and composed in very different ways. There were builders and entrepreneurs in London, particularly Sydney Waterlow, who developed several tenement blocks based on this model. The facades show clearly how the prototype was used as a module and multiplied both vertically and horizontally. In that respect, the number four was not at all important: it could have been eight or sixteen. Or, indeed two. In fact, the scheme was intended to be declinated into two different types of dwellings. One possibility was to use it as the basis for standard cottages, semi-detached houses for two families. In the other scenario, it could be a fragment of a much bigger house, a multi-story, multi-family house. It is such a basic proposal that it lends itself to all these variants.

Based on his writings, I imagine Roberts as a systematic and pragmatic man. He said, of course, ideally, workers should live in cottages with their own garden. But in the city, the scarcity and the high cost of ground pushed for a different solution, housing multiple families on several floors. The original prototype, the two-stories building, was nothing if not a compromise: a cottage without its pitched roof, an incomplete block of flats. In the 19th century, it would have appeared very weird to people. I think it still looks weird.

WAS THE NICHE (ON THE FAÇADE) MEANT TO BE AN ARTICULATED SPACE OF SOCIAL INTERACTION?

Unfortunately, we don’t know what Henry Roberts’s thought beyond what he wrote. The danger is that we get attached to the images and get compelled to project our own, contemporary values onto them. We must be very aware of that and create a distance from questions such as whether this was an urban gesture, or a space of encounter.

The niche you refer to is interesting because it is a space that’s meant to actually minimise encounter. At this point in time, it was seen as problematic that, say, the wife of one family could meet the man of another family in a space where they’re unsupervised. Its underlying reason was of course public health, namely the need to separate families in order to avoid the spread of disease, and naturally ventilate the shared spaces. Getting rid of a long corridor, where several people can meet, is a way of minimising potentially problematic encounters. There was a lot of emphasis on domestic privacy, so the houses needed to be separated from each other as much as possible. And in terms of whether this is a gesture towards the city, I very much doubt that it was meant in that way. The book has very little to say on questions of urban planning.

It was only later, towards the end of the 19th century, that architects were imbued with socialist ideas that really wanted to offer social mobility to the workers. But at this point in the middle of the 19th century, they just didn’t want people to get sick. So, the niche was about space and ventilation. Pragmatically, perhaps disappointingly so, it was really about minimising the risk of disease.

The niche was covered, but open to air circulation. A few years before the theory of cholera was demonstrated by John Snow, people still thought that cholera was just airborne and transmitted through bad smells (miasma). The need for ventilation was an obsession of reforming architects of the time. It also became an obsession for the working classes, but mostly in the opposite direction.

People who lived in these places were seen as hating draughts and doing everything they could to prevent their houses from getting colder. Architects discussed openly how to stop the inhabitants from sealing off their homes. The niche was open: you could not stuff it closed with some rags. It was a pragmatic way of ensuring that the common areas would remain ventilated – something we have ourselves become very attuned to nowadays.

WOULD YOU SAY THIS PROTOTYPE IS A HARBINGER OF MODERNISM?

Absolutely. I’m very interested in seeing it like that. The flat roof looks familiar to us – but it was really a way of showing that the prototype was an unfinished project, awaiting completion through mass production. It’s a project that will achieve completion, either through the addition of a pitched roof, in which case it becomes a conventional cottage, or through multiplication, in which case it becomes a multi-story tenement.

Some modernist mass housing, for example Ernst May’s Neue Frankfurt Siedlungen, looks strikingly like a Model House extruded to four to five floors, including the central niche.

That’s not only because of the modernist aesthetic, programmed to look ascetic, repetitive, and factory-made. But also because of the genuine, faultless pragmatism of the plans, with two dwellings opening on two sides of the common circulation core. Once you recognize this configuration you see it everywhere in housing, because it is so rational and economical. Roberts did not invent this configuration, which he had documented in older Scottish tenements. Still, he was almost certainly the first architect to employ it in a consistent manner, and to also write about it.

THIS MODEL HOUSE CAN BE PUT IN DIFFERENT LOCATIONS, AT VARIOUS DISTANCES FROM THE WORKPLACE.

WHAT IS THE LIVING QUALITY THAT COMPENSATES THE EVENTUAL DISCOMFORT GIVEN BY A LESS FAVOURABLE POSITION IN THE CITY?

The Roberts Model Houses display no interest whatsoever towards the context of their use, their location, or their impact on the urban environment. Notions of comfort, of life quality – all these are a moot point. The point is that this prototype can – and actually does – occur almost anywhere in the city. The architect’s focus was inward-looking, mostly on the individual dwelling, and particularly on its plan. The outer shell is mainly the consequence of what happens on the inside and the relation between these dwellings. The façade is a default of the plan, give or take a couple of flourishes.

This is very different from say the speculative Georgian terrace houses built in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries London, Bath, Dublin and so forth. Although they were also standardised and in fact highly typified, the underlying assumption was fundamentally different – one of decorum, of reflecting the inhabitants’ social and economic position.

The facades were codified to communicate to the outer world the status of their residents (sometimes misleadingly, of course): the focus was on elevations to tell the story. Whereas in the Model Houses, the focus was on correcting the domestic habits of a new social class, the urban labourer – and thus, on the plan.

At the time before the ideas of Roberts came to being, the notions of private and public among the members of working class – and the urban poor, which to a great extent they represented – were almost irrelevant. (Friedrich) Engels described St Giles’ Rookery as a lawless place, where “there are no front doors, there being nothing left to steal”. The slum carried within it this kind of strange, perverse, even life-threatening, form of commonality. But a certain type of slum dweller flourished in these nooks and crannies, in places where they could scurry into. Besides, a certain commonality came out of it, whether good or bad. So, in many cases, in many situations, the new model houses were not very popular among slum dwellers. They had to get used to the idea that they were trading a perversely understood freedom for obvious comfort.

Victorians introduced a different type of housing, based on aspirational middle-class values, and on the assumption of the inhabitants’ moral fibre. Their strategy was to separate, separate, separate - almost an application of the divide and rule principle. As Robin Evans said, Roberts’s prototype compartmentalised families to own dwellings and individuals to own rooms. You set apart the generations, the sexes, families from each other, you create what is basically a privacy problematic. For many workers, privacy was perhaps articulated for the first time in this kind of dwellings. Most of them were very poor immigrants from the countryside, where again, there’s a very different set of territories between the exterior and the interior of the house. So, the dwelling became an apparatus for creating a new urban citizen, the building block for the industrial society.

In practice, these dwellings proved to be better suited to the lower middle classes, artisans and clerks, people with regular wages who could always afford to pay rent. In fact, reform housing did not really cater for the most vulnerable members of society.

The idea of comfort was superfluous to all this. One would think that people who had lived in terrible conditions would be happy to suddenly have light, air, rooms, a sink and a toilet. Infrastructurally, this proposal was way ahead of its time. Roberts’s vision assumed that these people knew how to use a sink and a toilet, for that matter. In Paris, as late as 1912, architects were still planning a type of basic housing for the poor with communal bathrooms, because people were deemed incapable of using and cleaning their own bathrooms. In London, much of the nineteenth-century worker’s housing – the blocks of the Peabody Trust for example – were only fitted with bathrooms after World War Two.

WAS THERE AN INTENTION TO GIVE TO A BUILDING, BUILT FOR WORKING CLASS, A MORE NOBLE CONSTRUCTION, DRIVEN BY RULES OF CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE? THE STRONG SYMMETRY RESEMBLES A FORMALLY ACCEPTED IMAGE OF A PALAZZO.

Oh yes. The palazzo’s image is very much present in the multi-story version, if not that much in the Great Exhibition prototype. There was an intention to give dignity to this housing, to this new type of existence. The palazzo expression was tied into multi-story dwellings. It bestowed monumentality upon a certain morphology.

WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE COMPOSITION OF THE FACADE, IS IT SOMETHING THAT YOU IGNORE CONSIDERING ALL THE OTHER VALUES?

The appearance of the Model Houses fascinates me, but it fascinates me because it’s so alien, in the context of both its time and our time. It’s quite ugly, I think, in its proportions. As I mentioned already, these proportions were meant to be adopted, adapted, ameliorated one way or another. It’s a building that openly shows its incompleteness on the facade. It almost asks for it to be finished somehow else. I think it is intended to show its condition of a model house, and not a real one.

10.01.2022

伊琳娜-达维多维奇:你网站的标题是 "住宅所为何"。首先,就我而言,住宅是用来住人的。我对住宅的大规模生产更感兴趣,而不是它们作为独一无二的杰作的艺术性概念。标准化和大规模生产的住宅告诉我们在任一特定时期的社会的价值和愿望。作为一位历史学家,我对这种生产背后的起源和底层的意识形态感兴趣。这是我选择亨利-罗伯茨1851年创作的《四个家庭的样板房》的主要动机。

这个项目在当时是革命性的吗?

在他职业生涯的初期,罗伯茨是一个典型的维多利亚时代的建筑师:拥有舒适的社会地位,这儿做一个庄园,那儿做一个教堂。他的早期项目之一是贫困水手的庇护所,这成为更多慈善事业的种子。1844年,他成为改善工人阶级状况协会(S.I.C.L.C.)的名誉建筑师,这是一个由福音派良心驱动的慈善协会,也是一个重要的政治参与组织,其赞助人都是最高层人士。该协会的目标是,首先,为大众市场开发和推广样板房。其次,它试图生产、收集和交换关于工人可负担的住房的知识。通过他在S.I.C.L.C.的工作,罗伯茨获得了这些建筑师新兴话题的专业知识。

我们今天讨论的样板房是为了解决过度拥挤的贫民窟带来的危害,以及它们对城市的新居民——工人的身体和道德健康带来的威胁。或许,隐含的道德议程更为重要。这栋住宅提供了一种如何控制工人阶级的模式,既鼓励他们遵循与(资本主义)资产阶级相同的道德价值观。它的计划可以被看作是一种社会工程的方式。罗宾-埃文斯(Robin Evans)有一篇精彩的文章,《贫民窟与样板住房》(Rookeries and Model Dwellings),涉及到这个想法。(贫民窟与样板住房: 英国住房改革和私人空间的道德观,罗宾-埃文斯,AA档案,第10卷第1期,1978年)。

这座住宅是革命性的吗?简短的回答是肯定的。我们试图将它看作是第一座回应大众住房问题的住宅,甚至可能是尝试实现城市秩序的表达。如你所知,它是一种样板房,一种原型。它在1851年伦敦的万国博览会上展出,获得了成千上万人的参观,因此引起了广大国际观众的巨大兴趣。它真正的是一个产品——不仅在计划方面,也在施工方式上,甚至连造价和住宅合同都制定了。它的建造成本更低,重量更轻(亨利-罗伯茨获得了空心砖的防火建筑专利),比当时市场上的产品更方便和安全。这是一个在多个层面上创新的项目,旨在引起开发商的兴趣并进行大规模的生产。这个被视为从根本上改善工人生活条件的项目也将影响整个城市的卫生状况。因此,该项目得到了非常知名的人士的支持。在阿尔伯特亲王的亲自干预下,该项目被纳入了万博会。这是一个非常聪明的举动,这样一来,来自世界各地的成千上万的人参观了这个原型。它是非常基本的,并且由于其简单性而具有明显的可复制性。即使在今天,我们也能在住宅中看到它的后代。

我认为另一个革命性的发展是,它改变了建筑师在住宅生产方面的角色,这显然是一个社会问题。罗伯茨的职业生涯标志着出现了建筑师作为住宅专家的情况。在创作原型的同时,他写了一些论述、一些建筑目录、一些建筑手册《劳动阶级的住宅》(1850)。这本书最终成为其他国家的典范,其中一个例子是其法文翻译的故事。1850年在伦敦的拿破仑三世对改革——如我们所知——与城市公共工程事宜非常感兴趣。他非常兴奋,下令翻译该书,并将其分发给法国的所有地方当局。每个法国城市都有一本该手册的副本。让-多尔福斯(Jean Dollfus)于1853-54年在穆尔豪斯(Mulhouse)建造的著名的工人村(cite ouvrière),就是以罗伯茨的原型为基础的(Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie)。

当涉及到复制时,罗伯茨的样板房提议为四个家庭建造一栋楼,每个家庭都有自己的独立单元。这个数字重要吗?

其实并不重要。我把这个原型看作是一个片段——一段代码,旨在以非常不同的方式进行复制和组合。在伦敦有一些建筑商和企业家,特别是悉尼-沃特洛(Sydney Waterlow),他们在这个模型的基础上开发了几个住宅区。它们的立面清晰地展示了原型是如何被用作模块,并在垂直和水平方向上复制的。在这方面,4这个数字一点都不重要:它可以是8或16。或者,其实是2。事实上,该方案旨在分解为两种不同类型的住宅。一种可能性是将其作为标准平房的基础,即两个家庭的半独立式住宅。而另一种情况下,它可以成为一个更大的住宅的片段,一个多层、多家庭的住宅。这是一个如此基本的提议,它适合于所有这些变体。

根据他的著作,我设想罗伯茨是一个有系统和务实的人。他说,当然,在理想情况下,工人应该住在有自己的花园的平房里。但在城市中,地面的稀缺性和高成本推动了不同的解决方案,将多个家庭安置在几个楼层。最初的原型,即两层楼的建筑,仅仅是一种妥协:没有坡屋顶的平房,一个不完整的公寓楼。在19世纪,人们会觉得它非常奇怪。我认为它现在仍然看起来很怪。

这个壁龛(在外立面上)是为了成为一个社会互动的衔接空间吗?

不幸的是,我们不知道亨利-罗伯特的想法,除了他写的东西。危险的是,我们会依附于这些图像,并不得不将我们自己的、当代的价值观投射到它们身上。我们必须非常清楚这一点,并与诸如这是一个回应城市的姿态,还是一个相遇的空间这样的问题建立一段距离。

你提到的壁龛很有趣,因为它实际上是一个旨在减少接触的空间。在当时那个时间点上,一个家庭的妻子在一个没有监督的空间里和另一个家庭的男人见面,会被认为是有问题的。其根本原因当然是公共卫生,名义上需要将家庭分开,以避免疾病的传播,又有自然通风的共享空间。摆脱长长的走廊,几个人可以在那里见面,这是一种尽量减少潜在问题的相遇方式。有很多人强调家庭隐私,所以需要尽可能地将每户住宅相互分开。而就这是否是对城市的一种姿态而言,我非常怀疑它是否有这样的意图。这本书对城市规划的问题所言甚少。

只是到了后来,即19世纪末,建筑师们才受到社会主义思想的熏陶,真正想为工人们提供社会流动性。但在19世纪中期,他们只是不想让人们生病。因此,壁龛是关于空间和通风的。务实的说,也许令人失望的是,它确实是为了最大限度地减少疾病的风险。

壁龛被覆盖,但对空气流通开放。在约翰-斯诺(John Snow)证明霍乱理论的几年前,人们仍然认为霍乱是通过空气传播的,并且通过不良的气味(瘴气)传播。通风的需要是当时改革派建筑师们的一个心病。它也成为工人阶级的痴迷,但大多是在相反的方向。

住在这些地方的人被视为讨厌通风,并尽一切可能防止他们的住宅变冷。建筑师们公开讨论了如何阻止居民将他们的家封闭起来。壁龛是开放的:你不能用一些破布塞住它。这是一种务实的方式,以确保公共区域保持通风——这也是如今我们自己已经非常适应的事情。

你会说这个原型是现代主义的一个预兆吗?

当然是。我对看到它这样的状况非常感兴趣。平坦的屋顶对我们来说很熟悉——但这其实是一种方式,表明原型是一个未完成的项目,等待着通过大规模生产完成。这是一个将要完成的项目,要么通过增加斜屋顶,成为一个传统的平房,要么通过复制叠加,成为一个多层住宅。

一些现代主义的大规模住房,例如恩斯特-梅(Ernst May)的新法兰克福住区(Neue Frankfurt Siedlungen),看起来非常像一个被拉伸到四到五层的样板房,包括中央的壁龛。

这不仅是因为现代主义的美学,住宅被安排成了禁欲主义的、重复的和工厂制造的样子。还因为计划中真正的、无懈可击的实用主义,两套公寓在共享的交通核的两侧开放。一旦你认识到这种配置,你就会在住宅中处处看到它,因为它是如此经济与合理。罗伯茨并没有发明这种配置,他曾在苏格兰老式住宅中记录过这种配置。不过,他几乎可以肯定是第一个以持续的方式采用这种配置的建筑师,并且还写了下来。

这个样板房可以放在不同的地方,与工作场所保持不同的距离。

城市中不太有利的位置终究会给人带来不适,什么样的生活品质能弥补这种不适?

罗伯茨的样板房没有展示出对其使用语境、位置或城市环境影响的任何兴趣。舒适度和生活品质的概念——所有这些都是没有意义的。关键是,这种原型可以——而且实际上也确实——发生在城市的任何地方。建筑师的重点是内向的,主要是在公寓单体上,特别是在其平面上。表皮主要是内部发生的事情,和公寓间关系的结果。外立面是由平面默认的,或多或少有一些装饰。

这与十八和十九世纪在伦敦、巴斯、都柏林等地投机性建造的乔治亚联排住宅有很大不同。虽然它们也是标准化的,事实上也是高度类型化的,但其潜在的预设是根本不同的——一种礼节,反映居民的社会和经济地位。

外立面的设计是为了向外部世界传达其居民的地位(当然,有时是误导性的):重点是通过立面来讲述故事。而在样板房中,重点是纠正一个新的社会阶层——城市工人——的家庭习惯,因此,重点是平面。

在罗伯茨的想法出现之前,工人阶级成员间的私人和公共概念——以及在很大程度上他们所代表的城市贫民——大抵是无关紧要的。(弗里德里希) 恩格斯将圣客吉勒斯的贫民窟描述为一个无法无天的地方,在那里 “没有前门,没有剩下什么可偷”。贫民窟带有这种奇怪的、反常的、甚至危及生命的共通形式。但某种类型的贫民窟居民在这些角落和缝隙中,在他们可以窜入的地方蓬勃发展。此外,某种共性也由此产生,不管是好是坏。所以在许多情况下,新的样板房在贫民窟居民中不是很受欢迎。他们不得不习惯于这样的想法,即他们正在用一种反常理解的自由来换取明显的舒适。

维多利亚时代的人引入了一种不同类型的住宅,基于令人向往的中产阶级价值观,以及对居民道德品质的假设。他们的策略是分离、分离、分离——几乎是应用分而治之的原则。正如罗宾-埃文斯所说,罗伯茨的原型将家庭分隔到他们的寓所,将个人分隔到自己的房间。你把不同的代际、性别、家庭彼此分开,你创造了一个基本上是隐私的问题。对于许多工人来说,隐私也许是第一次在这种住宅中得到阐述。他们中的大多数人是来自农村的非常贫穷的移民,在那里,住宅的外部和内部之间有一套非常不同的领域。因此,住宅成为创造新的城市公民的工具,成为工业社会的基石。

在实践中,这些住宅被证明更适合于中下层阶级、工匠和文员,这些人有固定的工资,总是能够支付得起租金。事实上,改革后的住房并没有真正照顾到社会中最脆弱的成员。

舒适的想法对这一切属于多此一举。人们会认为,生活在恶劣条件下的人们会很高兴突然有了采光、空气、房间、水槽和厕所。在基础设施方面,这个建议远远领先于它的时代。对于这个问题,罗伯茨的设想里假定这些人知道如何使用水槽和马桶。在巴黎,直到1912年,建筑师们仍然在为穷人规划一种带有公共浴室的基本住房,因为这些人们被认为没有能力使用和清洁自己的浴室。在伦敦,许多19世纪的工人住房——例如皮博迪信托公司的街区——在第二次世界大战后才配备了浴室。

是否有意为工人阶级建造的房子给予一个更高贵的构筑物,并以古典建筑的规则驱使?强烈的对称性类似于一个形式上的府邸形象。

哦,是的。如果说在万博会上的原型中看不到那么多的话,府邸的形象在多层的版本中非常明显。有一个意图是给这种住宅,给这种新型的存在带来尊严。府邸的表达方式与多层住宅联系在一起。它赋予了某种形态学上的纪念性。

你怎么看外立面的构成,它是你考虑到所有其他的价值而去忽略的东西吗?

样板房的外观让我着迷,但它让我着迷是因为它是如此陌生,在它的时代和我们的时代背景下。我认为,它的比例相当丑陋。正如我已经提到的,这些比例是为了被采用,被调整,和被改善的。这是一个在立面上公开显示其不完整性的建筑。它几乎要求以某种其他方式完成。我认为它的目的是要显示它作为一个样板房的状况,而不是一个真实的住宅。

2022年01月10日

イリーナ・ダヴィドヴィッチ:ウェブサイトのタイトルは「家は何のためにあるのだろう」ですね。何よりもまず私は、家は人を住まわせるものだと認識しています。一回きりの傑作としての芸術的構想よりも、住宅の大量生産の方に興味があります。標準化され大量生産された住宅は、その時代の社会的価値や願望を物語ってくれるからです。歴史家としては、その生産背景にあるイデオロギーや原型に興味があるのです。ヘンリー・ロバーツによる1851年の四世帯のためのモデル住宅を選んだのもそれが主な理由です。

このプロジェクトは当時としては画期的なものだったのでしょうか?

ロバーツはキャリアをスタートさせた当初は、典型的なヴィクトリアン・アーキテクトでした。つまり社会的な地位としてもゆとりのある建築家として、こっちではマナーハウスを作り、あっちでは教会を作り、といった具合です。初期のプロジェクトの一つに貧窮した船員たちのためのシェルターのプロジェクトがありました。これが後に広がる慈善活動の種となりました。1844年、彼はS.I.C.L.C.(労者階級の状態改善協会)の名誉建築家となりました。この福音主義的良心に基づいた慈善団体は、強力なパトロンをもつ重要な政治的集団でした。この団体の目的は、まず第一に大衆へ向けた住宅モデルを開発し普及させること。そして次に、労働者のための手頃な住宅モデルをテーマとした知見を生産し収集し交換することでした。S.I.C.L.C.での活動を通して、ロバーツは建築家にとっての新しいテーマを専門知識として身につけたのです。

今日、議論するモデル住宅は、過密なスラム街で生じる危険、つまり新しい都市生活者としての労働者の身体的、道徳的健康に対する解決策として開発されたものです。おそらく、その裏に隠された道徳的意図の方がより重要だったのだと思われます。この家はブルジョワジー(資本家としての)と同じ道徳的価値観に従うように促すことで、労働者階級を統制する方法としてのモデルを示していたわけです。その計画は、社会工学の一種として理解することができるでしょうか。素晴らしいエッセイがありますよね。ロビン・エヴァンスの

「貧民窟とモデル住宅」です。そこでは、この考え方について触れられています。(「貧民窟とモデル住宅」: イギリスの住居改革とプライベートスペースの倫理 , AAファイル ,Vol: 10 No.1 1978)

この住宅は、革命的なものだったのか?短絡的に答えればイエスでしょう。大衆住宅の問題に答えた初めてのものであり、おそらく、都市の秩序を表現する試みとして捉えることもできるでしょう。ご存知のように、この住宅はモデル住宅、つまりプロトタイプなわけです。何十万もの来場者がいた1851年のロンドン万国博覧会に出展され、世界中の人々が大きな関心を寄せました。本格的なものだったのです - 単なる計画ではなく、施工方法、コスト、さらには契約方法まで考えられたものでした。当時の市場で流通していた方法と比べると施工面において、より安く軽く作れるものとして(中空レンガを使った耐火構造によるもので、ヘンリー・ロバーツは特許を取得していました。)都合も良く安全性も高いものでした。さまざまなレベルにおいて革新的なプロジェクトとして、開発者の興味を引き、大量に生産されることが意図されていました。労働者の生活環境の根本的改善は、街全体の衛生状態に影響を及ぼすと考えられていました。ですからプロジェクトは非常に著名な人々からの後ろ盾があったのです。万国博覧会に出展されることになったのもアルバート公の仲介があったからです。非常にクレバーなやり方でした。だからこそ世界中から何千もの人々が訪れ、目にすることができたのです。プロジェクトは非常にベーシックなものでした。そのシンプルさゆえに極めて複製しやすいものです。今日の住宅にも、その子孫を見ることができます。

もう一つ革命的であったことは、大きな社会的問題であった住宅生産に対しての建築家の役割を変えたということです。ロバーツのキャリアは、住宅の専門家としての建築家の出現を物語っています。彼は、プロトタイプの開発と並行して、論文でもあり、建設カタログでもあり、建築マニュアルである『勤労者階級の住宅』(1850)を執筆しています。これがいかにして他国においてのモデルとなったかを示す一例として、フランス語訳の経緯をお話ししましょう。ナポレオン3世は1850年にロンドンに滞在していました。彼は改革に大変興味を持っていました - ご存知のように - 都市の公共事業のことです。この本への熱意は、翻訳版をフランスの全自治体に配布するよう命じるほどでした。実際、フランスの全自治体がこのマニュアルのコピーを保有していました。ジャン・ドルフュスが1853 - 54年に建設したミュルーズにある有名なシテ・オヴリエール(労働者村)はロバーツのプロトタイプをもとにしたものです。(Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie)

複製に関して言えば、ロバーツのモデルハウスはそれぞれが独立したユニットをもつ四世帯のための一つの建物を想定しているわけですが、この数字が重要なのでしょうか?

そうではないと思います。私はこのプロトタイプをある断片と捉えています - さまざまな方法で複製され、構成されることが意図されたものとして。ロンドンにはビルダーも起業家もいましたから。特にシドニー・ウォーターロー。彼は、このモデルをもとにいくつかの長屋を開発しています。そのファサードを見ると、プロトタイプを一つのモジュールとして、水平にも垂直にも増殖していく様子がよくわかります。その点では、4という数字が全く重要というわけではなく、8でも16でも良いのです。いや2でもいいのかもしれませんが。実際のところ、この計画は二種類の住居タイプに分けられるよう考えられていました。一つ目は、標準的なコテージ、つまり二世帯のセミデタッドハウスの原則として。もう一つは、より大きな家、つまり多層階、多世帯の住宅の一断片として。ベーシックな提案であるがゆえに、こういったバリエーションに対応できるというわけです。

彼の著作から判断するに、ロバーツはシステマティックでプラグマティックな人物なのだと想像します。もちろん、理想的には労働者も自分の庭をもてるようなコテージに住むべきだ、と彼は言うわけですが。しかし、都心における土地の希少性やコストの問題のために別の解決策が推し進められたのです。複数の家族を複数のフロアで収容するという解決策です。原型となったのは、二階建ての建物です。はっきり言ってしまえば、何もないのです。勾配屋根のないコテージ。いや不完全なアパートといった感じでしょうか。19世紀には、とても奇妙に映ったことでしょうね。今見ても変だと思いますから。

ニッチ(ファサードにある)は、社交の場となることが意図されていたのでしょうか?

残念ながらヘンリー・ロバーツが何を考えていたのか、彼の著作以上のことはわかりません。私たちがそのイメージに近づきすぎてしまい、現代的な価値観を投影してしまうことは危険ですね。自覚すべきことは、ニッチが都市的なジェスチャーなのか、出会いのための空間なのか、といった問いからは距離を保つことです。

そのニッチは興味深い空間ですよ。なぜなら実際は、出会いを最小化するための空間だからです。当時は、家庭内の妻が、他の家庭の男性と監視されていない空間で出会うことは問題視されていました。その考えの根底には、もちろん公衆衛生的観点、つまり病気の蔓延を避けるために、家族同士を分離したり、共有空間の自然換気をすることが必要とされていました。複数の人が行き来することになる長い廊下をなくしてしまうことで、問題が発生する可能性を減らすことができたのです。家庭内のプライバシーが重要視されていましたし、家同士はできるだけ離す必要がありました。さて、このニッチが都市に対するジェスチャーであるかどうかですよね。疑わしいですね。彼の本には都市計画に関することは、ほとんど書かれていないのです。

建築家が社会主義的な思想に染まり、労働者に社会的流動性を促すことを本気で考えるようになったのも、この計画の少し後のことで、19世紀末のことです。19世紀半ばであったこの当時は、ただ病気を防ぐことだけが望まれていました。つまり、ニッチは空間と風通しのためにあるものでした。現実的で残念な感じはありますが、病気へのリスクを最小限に抑えるためだけのもの、ということです。

ニッチには屋根がついていますが、空気の循環のためにも開放されています。ジョン・スノウによってコレラの理論が実証される数年前まで、コレラは空気感染するもので、悪臭(瘴気)を通じて伝染すると考えられていました。換気の必要性は、当時の改革派の建築家たちのこだわりだったのです。労働者階級の人々もわかってはいましたが、多くが逆の方向へ向かってしまいました。

このような場所の住人は、隙間風を嫌い、家が冷え込むのを防ぐためなら何でもするだろうと思われていたのです。建築家たちは、住人が家を密閉するのをいかに阻止するか、公然と議論をしていました。ニッチならば開放されていて、布切れで詰めて塞ぐことなどできません。このニッチは、共用部の換気を確保するための現実的な方法でした - 今日、私たちがとても敏感になっている話題ですね。

このプロトタイプは、モダニズムの前兆だと言えるでしょうか?

もちろん。そういう意味でとても興味深く見ているのです。フラットルーフは私たちにとっては見慣れたものですが - 未完成のプロジェクトとして、量産化され完成されるのを待っていることを示す手法でもあるのです。勾配屋根をかけて従来のコテージにするのか、あるいは増殖させることで多層の長屋にするのか、どちらかの方法によって完成するプロジェクトなのです。

モダニズムの集合住宅、例えばエルンスト・マイの『ニュー・フランクフルト計画』はとりわけ、モデル住宅を、中央のニッチを含めて4、5階まで押し出したような外観に見えるのです。

そう見えるのは、禁欲的で、反復的で、工場生産的に見えるよう仕組まれたモダニズムの美学のせいだけではないでしょう。二つの住居の開口部が、共通動線としてのコアの二面に面しているという、本当の意味で過不足のないプランの実利性によるものでもあるでしょう。この構成に一度気づいてしまうと、あらゆる住宅に同じ構成があることにも気づくはずです。それが、とても合理的で経済的だからです。ロバーツはこの構成を発明したわけではなく、スコットランドの古い長屋から記録していたのです。ただ、この構成を使い続け、文章にした建築家としては、彼が最初の建築家であることは、間違いないでしょう。

このモデル住宅は、さまざまな場所に、つまり職場からの距離にかかわらず、どこにでも設置できるわけですが、都心の良くない環境の中では結局、不快感を感じてしまうのではないかと思われます。モデル住宅にそれを補うような生活の質があるとすれば、それはどういうものでしょうか?

ロバーツのモデル住宅は、それが使用される状況や設置場所、それに都市環境への影響に対しては全く関心を示していません。快適性や生活の質といった考え - それらは全く無意味なことなのでしょう。重要なのは、このプロトタイプがたいていの都市において実現可能な - そして実際に実現されている - ことなのです。建築家の関心は内 - 向きなもので、たいていは個々の住居、特にプランに向けられていました。外壁面は主に、内部での現象や住居間の関係性の結果であり、ファサードは、ただプランの原理が反映されたものとして、そこに多少の飾り付けがあろうが無かろうがどちらでも良いのです。

これは、18世紀から19世紀にかけてロンドンやバース、ダブリンなどに建てられた投機的なジョージアン様式のテラスハウスとは全く異なるものです。標準化され高度に類型化されたものとしては同じですが、根底にある考えが根本的に違っていて - ファサードは住人の社会的、経済的地位を反映する礼儀の一つなのです。

ファサードは住人のステータス(時には誤解を招くことももちろんあるのですが)を外の世界へ伝えるために成文化されたものでした。つまり立面図に焦点が当てられていました。一方、モデル住宅は、新しい社会階層である都市労働者の生活習慣を正すことに焦点が当てられていました - つまり平面図が重要だというわけです。

ロバーツの思想が生まれる前には、労働者階級 - 彼らが都市の貧困層の大部分であるわけですが - の間ではプライベートとパブリックといった概念はほとんど無意味なものでした。(フリードリヒ)エンゲルスは、セント・ジャイルズの貧困窟のことを、玄関がなく盗む物も何もない無法地帯だと表現しています。スラム街は、このように、奇妙で倒錯的で、それに命の危険性さえある場所として共通していました。住人の一部は、スラム街の隅々まで入り込むようにして生活していましたし、良くも悪くも、そこにはある種のコモンセンスが生まれていたのです。ですから、たいていの場合、新しいモデル住宅はスラムの住人にとってそんなに良くは思われていませんでした。彼らは、意固地な自由さと引き換えに、屈託のない心地良さを手にする、という考えに慣れる必要がありました。

ヴィクトリア朝は、意欲的な中流階級の価値観や、住民の道徳心を前提としたさまざまなタイプの住宅を取り入れました。そこでの戦略は、分離、分離、分離 - つまりほとんどが分割と統治の原則を応用したものでした。ロビン・エバンスによれば、ロバーツのプロトタイプは、家族には住居を、個人には部屋を供給するという分離を行ったものでした。世代、性別、家族をそれぞれ別にすることで生じてくるのは基本的にプライバシーの問題です。多くの労働者にとっては、プライバシーとは、おそらくこのような住居で初めて明示されたものなのです。彼らの多くは田舎からの貧しい移民でしたし、家の外部と内部との領域の関係に対する考えは、全く違っていました。つまり、住居は新しい都市市民を作り出すための装置であり、産業社会の基礎を作るものだったのです。

実際問題として、このような住居は、中流階級以下の職人や事務員などの定期賃金があり、家賃を毎月支払う余裕のある人々に適したものであることが証明されてしまったわけですが。事実として、改革住宅は、社会の中で最も弱い立場の人々のためとはならなかったのです。

快適さという概念は、この際、余計なものでした。ひどい環境で暮らしてきた人々が突然、光や空気、個室にシンク、それにトイレを手に入れたら喜ぶだろう、と普通そう思いますよね。インフラとしても、この提案は時代を先取りしたものでした。ロバートのビジョンは、こういった人々がシンクやトイレの使い方を知っていることを前提としていました。パリでは1912年の時点においても、建築家たちが計画していた貧困層のための最小限住宅は共同浴槽でした。なぜなら、個人の浴室が綺麗に使われるとは考えていなかったからです。ロンドンでは、19世紀の労働者住宅 - 例えばピーボディ・トラスト - の多くは、第二次世界大戦後になってようやく浴室がつくようになったのです。

労働者階級のための建物を、古典建築の原則によって高貴なものにしようとする意図があったのでしょうか?強いシンメトリーは、形式的にかの名高いパラッツォのイメージと似ていると感じるのですが。

まさに。そうなんです。パラッツォ的なイメージは、多層階になった時に強く表れていますね。大博覧会の時のプロトタイプにはそれほど表れてはいないですが。新しい存在としてのこの住宅に、威厳を与えようという意図があったのだと思います。パラッツォ的表現が多層階の住居と結びつき、ある種の形態学にモニュメンタリティが与えられたのです。

ファサードの構成に関してはどう思われますか?このモデル住宅の他の価値と比べれば、無視しても良いようなものですか?

モデル住宅の外観は魅力的ですよ。当時もそうですし、今見てもかなり異様ですね。すごい不細工ですよね。プロポーション的に。先に述べたように、このプロポーションが示しているのは、このモデル住宅が何らかの形で選択され、適応され、改善される可能性なのだと思います。ファサードの未完成性を公然と見せつけている建物。ともかく完成させてくれと訴えかけているようです。モデル住宅としての、ある状況を示しているのでしょう。本物としてではなく。

2022年01月10日

Irina Davidovici: The title of your website is „what is a house for”. Primarily, as far as I am concerned, a house is for housing people. I’m more interested in the mass production of houses than their artistic conception as one-off masterpieces. Standardised and mass-produced houses tell us about the values and aspirations of society at any given time. And as a historian, I am interested in the origin and underlying ideologies behind their production. This was my main motivation for choosing the Model Houses for Four Families by Henry Roberts from 1851.

WAS THIS PROJECT REVOLUTIONARY AT THE TIME?

At the beginning of his career Roberts was a typical Victorian architect: of comfortable social standing, doing a manor house here, a church there. One of his early projects was a shelter for destitute sailors, which became the seed for more philanthropic works. In 1844, he became Honorary Architect to the Society for Improving the Conditions of the Labouring Classes (S.I.C.L.C.), a charitable society animated by evangelical conscience and a significant political player, with patrons in the highest places. This society aimed, firstly, to develop and promote housing models for the mass market. Secondly, it sought to produce, collect and exchange knowledge on the topic of affordable housing for labourers. Through his work for S.I.C.L.C., Roberts gained expertise on what was an emerging topic for architects.

The model house we discuss today was developed as a solution to the dangers brought about by overcrowded slums, the threats they brought to the bodily and moral health of the new urban dweller, the labourer. Possibly, the hidden moral agenda was the more important. This house offered a model of how to control the working classes, by encouraging them to adhere to the same set of moral values as the (capitalist) bourgeoisie. Its planning can be seen as a manner of social engineering. There’s a wonderful essay, ‘Rookeries and Model Dwellings’ by Robin Evans that deals with this idea. („Rookeries and Model Dwelling: English Housing Reform and the Moralities of Private Space’, Robin Evans, AA Files, Vol: 10 No.1 1978).

Was the house revolutionary? The short answer is yes. We are tempted to see it as the first house that responded to the question of mass housing, perhaps even the expression of an attempt to bring about urban order. As you know, it’s a model house, a prototype. It was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, visited by hundreds of thousands of people, and as such it elicited a huge amount of interest from an extended international audience. It was a true product – not only in terms of planning but also methods of construction, even the costs and residential contracts were worked out. It was cheaper and lighter to construct (Henry Roberts patented a type of fireproof construction with hollow bricks), more expedient, safer than what was at that time available on the market. It was an innovative project at several levels, meant to interest developers and be produced en masse. What was seen as a radical improvement of living conditions of workers was also to affect the hygienic condition of the entire city. So the project was backed by very prominent people. It was included in the Great Exhibition at the personal intervention of Prince Albert. This was a very clever move, for in this way the prototype was visited by thousands of people from all over the world. It was very basic and on account of its simplicity eminently replicable. We see its progeny in housing even today.

Something else I see as a revolutionary development was that it changed the role of architects in relation to the production of housing, eminently a social matter. Roberts’s career marks the emergence of the architect as housing expert. In parallel with the prototype he wrote the part-treatise, part constructional catalogue, part-building manual ‘The Dwellings of the Labouring Classes’ (1850). One example of how this eventually became a model for other countries is the story of its French translation. Napoleon III, who was in London in 1850, was very interesting in matters of reform and – as we know – urban public works. He was so enthused that he ordered its translation and had it distributed to all local authorities in France. Every French municipality had a copy of this manual. The famous cite ouvrière (workers’ village) in Mulhouse, built by Jean Dollfus in 1853-54, was based on Roberts’s prototype (Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie).

WHEN IT COMES TO BEING REPLICATED, THE MODEL HOUSE BY ROBERTS PROPOSES ONE BUILDING FOR FOUR FAMILIES, EACH IN ITS OWN SEPARATE UNIT. IS THIS NUMBER IMPORTANT?

Not really. I see this prototype as a fragment - a piece of code, meant to be replicated and composed in very different ways. There were builders and entrepreneurs in London, particularly Sydney Waterlow, who developed several tenement blocks based on this model. The facades show clearly how the prototype was used as a module and multiplied both vertically and horizontally. In that respect, the number four was not at all important: it could have been eight or sixteen. Or, indeed two. In fact, the scheme was intended to be declinated into two different types of dwellings. One possibility was to use it as the basis for standard cottages, semi-detached houses for two families. In the other scenario, it could be a fragment of a much bigger house, a multi-story, multi-family house. It is such a basic proposal that it lends itself to all these variants.

Based on his writings, I imagine Roberts as a systematic and pragmatic man. He said, of course, ideally, workers should live in cottages with their own garden. But in the city, the scarcity and the high cost of ground pushed for a different solution, housing multiple families on several floors. The original prototype, the two-stories building, was nothing if not a compromise: a cottage without its pitched roof, an incomplete block of flats. In the 19th century, it would have appeared very weird to people. I think it still looks weird.

WAS THE NICHE (ON THE FAÇADE) MEANT TO BE AN ARTICULATED SPACE OF SOCIAL INTERACTION?

Unfortunately, we don’t know what Henry Roberts’s thought beyond what he wrote. The danger is that we get attached to the images and get compelled to project our own, contemporary values onto them. We must be very aware of that and create a distance from questions such as whether this was an urban gesture, or a space of encounter.

The niche you refer to is interesting because it is a space that’s meant to actually minimise encounter. At this point in time, it was seen as problematic that, say, the wife of one family could meet the man of another family in a space where they’re unsupervised. Its underlying reason was of course public health, namely the need to separate families in order to avoid the spread of disease, and naturally ventilate the shared spaces. Getting rid of a long corridor, where several people can meet, is a way of minimising potentially problematic encounters. There was a lot of emphasis on domestic privacy, so the houses needed to be separated from each other as much as possible. And in terms of whether this is a gesture towards the city, I very much doubt that it was meant in that way. The book has very little to say on questions of urban planning.

It was only later, towards the end of the 19th century, that architects were imbued with socialist ideas that really wanted to offer social mobility to the workers. But at this point in the middle of the 19th century, they just didn’t want people to get sick. So, the niche was about space and ventilation. Pragmatically, perhaps disappointingly so, it was really about minimising the risk of disease.

The niche was covered, but open to air circulation. A few years before the theory of cholera was demonstrated by John Snow, people still thought that cholera was just airborne and transmitted through bad smells (miasma). The need for ventilation was an obsession of reforming architects of the time. It also became an obsession for the working classes, but mostly in the opposite direction.

People who lived in these places were seen as hating draughts and doing everything they could to prevent their houses from getting colder. Architects discussed openly how to stop the inhabitants from sealing off their homes. The niche was open: you could not stuff it closed with some rags. It was a pragmatic way of ensuring that the common areas would remain ventilated – something we have ourselves become very attuned to nowadays.

WOULD YOU SAY THIS PROTOTYPE IS A HARBINGER OF MODERNISM?

Absolutely. I’m very interested in seeing it like that. The flat roof looks familiar to us – but it was really a way of showing that the prototype was an unfinished project, awaiting completion through mass production. It’s a project that will achieve completion, either through the addition of a pitched roof, in which case it becomes a conventional cottage, or through multiplication, in which case it becomes a multi-story tenement.

Some modernist mass housing, for example Ernst May’s Neue Frankfurt Siedlungen, looks strikingly like a Model House extruded to four to five floors, including the central niche.

That’s not only because of the modernist aesthetic, programmed to look ascetic, repetitive, and factory-made. But also because of the genuine, faultless pragmatism of the plans, with two dwellings opening on two sides of the common circulation core. Once you recognize this configuration you see it everywhere in housing, because it is so rational and economical. Roberts did not invent this configuration, which he had documented in older Scottish tenements. Still, he was almost certainly the first architect to employ it in a consistent manner, and to also write about it.

THIS MODEL HOUSE CAN BE PUT IN DIFFERENT LOCATIONS, AT VARIOUS DISTANCES FROM THE WORKPLACE.

WHAT IS THE LIVING QUALITY THAT COMPENSATES THE EVENTUAL DISCOMFORT GIVEN BY A LESS FAVOURABLE POSITION IN THE CITY?

The Roberts Model Houses display no interest whatsoever towards the context of their use, their location, or their impact on the urban environment. Notions of comfort, of life quality – all these are a moot point. The point is that this prototype can – and actually does – occur almost anywhere in the city. The architect’s focus was inward-looking, mostly on the individual dwelling, and particularly on its plan. The outer shell is mainly the consequence of what happens on the inside and the relation between these dwellings. The façade is a default of the plan, give or take a couple of flourishes.

This is very different from say the speculative Georgian terrace houses built in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries London, Bath, Dublin and so forth. Although they were also standardised and in fact highly typified, the underlying assumption was fundamentally different – one of decorum, of reflecting the inhabitants’ social and economic position.

The facades were codified to communicate to the outer world the status of their residents (sometimes misleadingly, of course): the focus was on elevations to tell the story. Whereas in the Model Houses, the focus was on correcting the domestic habits of a new social class, the urban labourer – and thus, on the plan.

At the time before the ideas of Roberts came to being, the notions of private and public among the members of working class – and the urban poor, which to a great extent they represented – were almost irrelevant. (Friedrich) Engels described St Giles’ Rookery as a lawless place, where “there are no front doors, there being nothing left to steal”. The slum carried within it this kind of strange, perverse, even life-threatening, form of commonality. But a certain type of slum dweller flourished in these nooks and crannies, in places where they could scurry into. Besides, a certain commonality came out of it, whether good or bad. So, in many cases, in many situations, the new model houses were not very popular among slum dwellers. They had to get used to the idea that they were trading a perversely understood freedom for obvious comfort.

Victorians introduced a different type of housing, based on aspirational middle-class values, and on the assumption of the inhabitants’ moral fibre. Their strategy was to separate, separate, separate - almost an application of the divide and rule principle. As Robin Evans said, Roberts’s prototype compartmentalised families to own dwellings and individuals to own rooms. You set apart the generations, the sexes, families from each other, you create what is basically a privacy problematic. For many workers, privacy was perhaps articulated for the first time in this kind of dwellings. Most of them were very poor immigrants from the countryside, where again, there’s a very different set of territories between the exterior and the interior of the house. So, the dwelling became an apparatus for creating a new urban citizen, the building block for the industrial society.

In practice, these dwellings proved to be better suited to the lower middle classes, artisans and clerks, people with regular wages who could always afford to pay rent. In fact, reform housing did not really cater for the most vulnerable members of society.

The idea of comfort was superfluous to all this. One would think that people who had lived in terrible conditions would be happy to suddenly have light, air, rooms, a sink and a toilet. Infrastructurally, this proposal was way ahead of its time. Roberts’s vision assumed that these people knew how to use a sink and a toilet, for that matter. In Paris, as late as 1912, architects were still planning a type of basic housing for the poor with communal bathrooms, because people were deemed incapable of using and cleaning their own bathrooms. In London, much of the nineteenth-century worker’s housing – the blocks of the Peabody Trust for example – were only fitted with bathrooms after World War Two.

WAS THERE AN INTENTION TO GIVE TO A BUILDING, BUILT FOR WORKING CLASS, A MORE NOBLE CONSTRUCTION, DRIVEN BY RULES OF CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE? THE STRONG SYMMETRY RESEMBLES A FORMALLY ACCEPTED IMAGE OF A PALAZZO.

Oh yes. The palazzo’s image is very much present in the multi-story version, if not that much in the Great Exhibition prototype. There was an intention to give dignity to this housing, to this new type of existence. The palazzo expression was tied into multi-story dwellings. It bestowed monumentality upon a certain morphology.

WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE COMPOSITION OF THE FACADE, IS IT SOMETHING THAT YOU IGNORE CONSIDERING ALL THE OTHER VALUES?

The appearance of the Model Houses fascinates me, but it fascinates me because it’s so alien, in the context of both its time and our time. It’s quite ugly, I think, in its proportions. As I mentioned already, these proportions were meant to be adopted, adapted, ameliorated one way or another. It’s a building that openly shows its incompleteness on the facade. It almost asks for it to be finished somehow else. I think it is intended to show its condition of a model house, and not a real one.

10.01.2022

伊琳娜-达维多维奇:你网站的标题是 "住宅所为何"。首先,就我而言,住宅是用来住人的。我对住宅的大规模生产更感兴趣,而不是它们作为独一无二的杰作的艺术性概念。标准化和大规模生产的住宅告诉我们在任一特定时期的社会的价值和愿望。作为一位历史学家,我对这种生产背后的起源和底层的意识形态感兴趣。这是我选择亨利-罗伯茨1851年创作的《四个家庭的样板房》的主要动机。

这个项目在当时是革命性的吗?

在他职业生涯的初期,罗伯茨是一个典型的维多利亚时代的建筑师:拥有舒适的社会地位,这儿做一个庄园,那儿做一个教堂。他的早期项目之一是贫困水手的庇护所,这成为更多慈善事业的种子。1844年,他成为改善工人阶级状况协会(S.I.C.L.C.)的名誉建筑师,这是一个由福音派良心驱动的慈善协会,也是一个重要的政治参与组织,其赞助人都是最高层人士。该协会的目标是,首先,为大众市场开发和推广样板房。其次,它试图生产、收集和交换关于工人可负担的住房的知识。通过他在S.I.C.L.C.的工作,罗伯茨获得了这些建筑师新兴话题的专业知识。

我们今天讨论的样板房是为了解决过度拥挤的贫民窟带来的危害,以及它们对城市的新居民——工人的身体和道德健康带来的威胁。或许,隐含的道德议程更为重要。这栋住宅提供了一种如何控制工人阶级的模式,既鼓励他们遵循与(资本主义)资产阶级相同的道德价值观。它的计划可以被看作是一种社会工程的方式。罗宾-埃文斯(Robin Evans)有一篇精彩的文章,《贫民窟与样板住房》(Rookeries and Model Dwellings),涉及到这个想法。(贫民窟与样板住房: 英国住房改革和私人空间的道德观,罗宾-埃文斯,AA档案,第10卷第1期,1978年)。

这座住宅是革命性的吗?简短的回答是肯定的。我们试图将它看作是第一座回应大众住房问题的住宅,甚至可能是尝试实现城市秩序的表达。如你所知,它是一种样板房,一种原型。它在1851年伦敦的万国博览会上展出,获得了成千上万人的参观,因此引起了广大国际观众的巨大兴趣。它真正的是一个产品——不仅在计划方面,也在施工方式上,甚至连造价和住宅合同都制定了。它的建造成本更低,重量更轻(亨利-罗伯茨获得了空心砖的防火建筑专利),比当时市场上的产品更方便和安全。这是一个在多个层面上创新的项目,旨在引起开发商的兴趣并进行大规模的生产。这个被视为从根本上改善工人生活条件的项目也将影响整个城市的卫生状况。因此,该项目得到了非常知名的人士的支持。在阿尔伯特亲王的亲自干预下,该项目被纳入了万博会。这是一个非常聪明的举动,这样一来,来自世界各地的成千上万的人参观了这个原型。它是非常基本的,并且由于其简单性而具有明显的可复制性。即使在今天,我们也能在住宅中看到它的后代。

我认为另一个革命性的发展是,它改变了建筑师在住宅生产方面的角色,这显然是一个社会问题。罗伯茨的职业生涯标志着出现了建筑师作为住宅专家的情况。在创作原型的同时,他写了一些论述、一些建筑目录、一些建筑手册《劳动阶级的住宅》(1850)。这本书最终成为其他国家的典范,其中一个例子是其法文翻译的故事。1850年在伦敦的拿破仑三世对改革——如我们所知——与城市公共工程事宜非常感兴趣。他非常兴奋,下令翻译该书,并将其分发给法国的所有地方当局。每个法国城市都有一本该手册的副本。让-多尔福斯(Jean Dollfus)于1853-54年在穆尔豪斯(Mulhouse)建造的著名的工人村(cite ouvrière),就是以罗伯茨的原型为基础的(Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie)。

当涉及到复制时,罗伯茨的样板房提议为四个家庭建造一栋楼,每个家庭都有自己的独立单元。这个数字重要吗?

其实并不重要。我把这个原型看作是一个片段——一段代码,旨在以非常不同的方式进行复制和组合。在伦敦有一些建筑商和企业家,特别是悉尼-沃特洛(Sydney Waterlow),他们在这个模型的基础上开发了几个住宅区。它们的立面清晰地展示了原型是如何被用作模块,并在垂直和水平方向上复制的。在这方面,4这个数字一点都不重要:它可以是8或16。或者,其实是2。事实上,该方案旨在分解为两种不同类型的住宅。一种可能性是将其作为标准平房的基础,即两个家庭的半独立式住宅。而另一种情况下,它可以成为一个更大的住宅的片段,一个多层、多家庭的住宅。这是一个如此基本的提议,它适合于所有这些变体。

根据他的著作,我设想罗伯茨是一个有系统和务实的人。他说,当然,在理想情况下,工人应该住在有自己的花园的平房里。但在城市中,地面的稀缺性和高成本推动了不同的解决方案,将多个家庭安置在几个楼层。最初的原型,即两层楼的建筑,仅仅是一种妥协:没有坡屋顶的平房,一个不完整的公寓楼。在19世纪,人们会觉得它非常奇怪。我认为它现在仍然看起来很怪。

这个壁龛(在外立面上)是为了成为一个社会互动的衔接空间吗?

不幸的是,我们不知道亨利-罗伯特的想法,除了他写的东西。危险的是,我们会依附于这些图像,并不得不将我们自己的、当代的价值观投射到它们身上。我们必须非常清楚这一点,并与诸如这是一个回应城市的姿态,还是一个相遇的空间这样的问题建立一段距离。

你提到的壁龛很有趣,因为它实际上是一个旨在减少接触的空间。在当时那个时间点上,一个家庭的妻子在一个没有监督的空间里和另一个家庭的男人见面,会被认为是有问题的。其根本原因当然是公共卫生,名义上需要将家庭分开,以避免疾病的传播,又有自然通风的共享空间。摆脱长长的走廊,几个人可以在那里见面,这是一种尽量减少潜在问题的相遇方式。有很多人强调家庭隐私,所以需要尽可能地将每户住宅相互分开。而就这是否是对城市的一种姿态而言,我非常怀疑它是否有这样的意图。这本书对城市规划的问题所言甚少。

只是到了后来,即19世纪末,建筑师们才受到社会主义思想的熏陶,真正想为工人们提供社会流动性。但在19世纪中期,他们只是不想让人们生病。因此,壁龛是关于空间和通风的。务实的说,也许令人失望的是,它确实是为了最大限度地减少疾病的风险。

壁龛被覆盖,但对空气流通开放。在约翰-斯诺(John Snow)证明霍乱理论的几年前,人们仍然认为霍乱是通过空气传播的,并且通过不良的气味(瘴气)传播。通风的需要是当时改革派建筑师们的一个心病。它也成为工人阶级的痴迷,但大多是在相反的方向。

住在这些地方的人被视为讨厌通风,并尽一切可能防止他们的住宅变冷。建筑师们公开讨论了如何阻止居民将他们的家封闭起来。壁龛是开放的:你不能用一些破布塞住它。这是一种务实的方式,以确保公共区域保持通风——这也是如今我们自己已经非常适应的事情。

你会说这个原型是现代主义的一个预兆吗?