私たちは絶え間ない変化と探求の時代に生きています。例えば、自身のルーツと強い結びつきを保っているような人はどれほどいるのでしょうか?私たちは、若い時から旅をしながら視野を広げ、新しい場所や文化を体験してきました。働いたり、観光したりしながら、学んでいくことでヨーロッパ文化を広く理解することができました。そうして世界も同じように理解することができるのだと思いますし、それはとても素晴らしいことだと思います。ところが、弊害も生じます。つまり、転々と場所を移動することで、自分がどこからきたのか、どう物事を理解しているのかを簡単に見失ってしまうのです。私自身もそうだったのかもしれません。ただ、そのことに意識的ではありましたし、マリオ・メルツの作品「ザップのイグルー」に用いられた、戦いの中で直面する危険を表現するために使われた言葉をよく思い出していました。「敵が軍勢を集めれば敗れ、散らせば勢力を失う」。

今日では、建築家が様々な文脈の中で思考し、活動することは普通なことです。むしろ、歓迎されていることではないでしょうか。この状況に関してはどう思われますか?そうあるべきだとお考えですか?

むしろ逆ですね。作品のポートフォリオを広げていくよりも、一つの地域にとどまることで、その地域の文化的景観に深く根ざした建築的思考を創造する、そういったことを選ぶ建築家もいます。私たちはそちらの方が魅力に感じます。

ディミトリス・ピキオニス(1887-1968)は晩年になって、アッティカの風景にのめり込んでいきました。彼の全ての作品はその風景に影響されたものです。アテネのアクロポリス周辺の遺跡のランドスケープをその土地にある素材と労働力だけで作り上げました。プランなど必要ありませんでした。しっかり作業を管理して、あとは熟練工の助けがあればよかったのです。地中海のまた別の地域では、アルベルト・ポニス(1933年)がサルデーニャ島のパラオに移住しています。その土地での学びに全てを捧げ、すっかりと溶け込んでいました。机の上には、何百もの家の設計図が広げられ、いくつかのユニークな建物が実現しています。同じように、ジェフリー・バワ(1919-2003)は、現代的な感覚でスリランカを捉えています。

そして、ルドルフ・オルジアティ(1910-1995)はクールで生まれ、働き、その生涯をグラウビュンデンで過ごしました。彼のルーツはスイスのアルプスの中にあります。オルジアティはファミリー向けの住宅を建てたり、古い農家を修復したりしていたわけですが、一人で仕事していましたし、地元でも近寄りがたい存在であったようです。彼のサインは明白なものですが、スタイルを確立したり、スクールを作ったりするようなことはせず、いかなる組織にも所属しようとしなかった。こうした閉じた環境の中で、大衆の好みに左右されることなく、強靭な建築的ビジョンに集中するための時間と静けさを彼は手に入れていたのです。オルジアティは、大きな議論や運動には無関心ではあったものの、彼のフリムスにあるスタジオは長年に渡って、チューリッヒ工科大学建築学科の若い建築家たちの思考と学習の実験場となっていました。彼の死後、その関心はおそらく生前よりも高まっていて、最近のスイスの建築家たちの世代にも影響を与え続けています。

彼の作品はどういったものなのでしょうか?

彼の作品は、地域の伝統的な風土と進歩的なモダニズムの精神を見事に融合させるとともに、アルプスの風景に対して美しく繊細であり続けています。ピーター・メルクリが述べるには、彼は、小さな住宅を特別な巣窟のようなものとして捉えていて、設計にあたっては厳格なアプローチを持っていたのだと。つまりそれは、変更することができないほどに繊細な質とディテールによって整えられたものであるべきだと。彼の設計した家は、独立したヴォリュームで、しばしば傾斜地に配置され、巨大な白い外壁が対照的な特徴を作り出していて、面取りされた窓、特定の方角への大きな開口、単純な勾配をもった石の屋根、搭状の煙突、アーチ型のドア、大きな柱、ニッチ、光あふれる場所、暗いコーナー、それらすべてを均衡させた全体性を求める、完全な作品なのです。彼の興味や美意識を元に作られる、深く個人的なものでもありますが。

室内から見ると、部屋は対称的な関係から解放され、特定の活動のために形作られています。彼は、現代の私たちがもっぱら考えているような「フレキシブルな空間」というドグマに縛られることはなかったのです。一方で、彼の作品は、人々の暮らしから生まれた空間の原型についてまとめられた、クリストファー・アレグサンダーの著書「パタン・ランゲージ」を思い起こさせます。ルドルフ・オルジアティは、一般的な習慣に対応し、建築とそこに住む人々との関係を模索したのです。それと同時に、古代ギリシャ建築や、ル・コルビュジエの後期彫刻的作品への憧れによって、文化的景観に根ざしたそれまでの態度を改めることになります。この対立が、彼の建築に一種の緊張感、あるいは神秘性を生み出しているのですが、これは説明するのが難しいですね。

一見、彼の建築はとても自律した力強いものに見えます。しかし、住宅は内側から外側へ、各部屋を使う住人の視点から設計されており、外形は結果的なものなのです。ある意味、彼は形やスタイルの問題には無頓着でした。

窓は、ファサードの幾何学的形状や、軸の配置に対応することはありません。大きな開口部を角に設けたり、分厚い壁面の中央に小さな開口部を配置する自由さ。そして、エンガディンの巨大な農家の外観に共通するテーマである、影と光の間の、激しいコントラストと「キアロスクーロ」の探求に気付くでしょう。この意味において、一人の優れた彫刻家としての、統一された全体の中で、各要素を均衡させることを意図したヴォリューム操作に、芸術的なアプローチを見ることができます。彼は、フォルムの存在感や、そのグラデーションを理解している人でした。

ハウス・チャラーをどのようにして知りましたか?

私たちは、自分たちの事務所を設立する以前、クールに住み、アトリエ・ピーター・ズントーで8年間働いていました。 ハウス・チャラーは、クール旧市街の著名な住宅兼商業ビルで、北側のオブレ・ガッセに面した19世紀の装飾が目を引くファサードは、アーティストのシュタイフン・リウン・クンツによって美しく修復されており、それはこの住宅の目印にもなっています。1970年代後半に、ルドルフ・オルジアティがこの家を改築し、全体の動線、建物の南側、そしてインテリアの大部分を変更しました。1階には、ガラス張りのコーナーに小さなショップがあり、南側には小さな庭のある人気のカフェの入り口があります。元々、この建物は一軒のアパートでしたが、オルジアティはこれを、11の小さなワンルームアパートに分割しました。

私たちが住んでいたのは屋根の下のロフト空間で、そこはアルプス地方では伝統的に倉庫として使われていました。室内から見ると、屋根は常に思い出の要素であり、滑らかな白い壁とは対照的に、むき出しの木造梁が見えます。北側の通りに面した窓(切妻屋根で他の窓よりかなり大きい)からは、歴史的な町並みを見渡すことができます。部屋に入るには、ドアの高さが低いので、頭を下げなければなりませんが、メインルームの天井には勾配があり、中央の頂部は非常に高くなっています。

あちこちにニッチやアルコーブがあり、それらは寝床や、書斎、料理用の小さな腰掛けなどになり、まるでテントの下にいるようでした。このアパートにあるものはすべて小さいのですが、空間の豊かさは比類のないものです。

グラウビュンデンは、建築的に非常に重要な地域であり、クラフトマンシップの伝統が建築分野において受け継がれてきています。ここは現在に至るまで、人々の保養地であったわけですが、それにもいくつかの理由があるのでしょう。ここでの孤立的状況は、現実逃避を可能にしてくれます。厳かな問いなどに悩むようなことなどなく、ある意味、純粋な状態でいられますし、体に染み付いた都市的考えからも解放され、小さなスケールの物事に楽しさや美しさを感じることができるのでしょう。例えば、ハウス・チャラーの南西のファサードは、ある種の実用主義によって完全に切り取られるように改築されていて、彫刻的な要素としての角ばったバルコニーが、拳の指の関節のように、屋根を切り取っています。この過激でモダンな増築は、歴史的な旧市街の北側ファサードとは対照的です。北側には、赤い装飾が施された壁面を残すことで、歴史的なこの住宅の精神は保たれたまま、古い町並みの全体的な印象の中に、この建物を残すことができたのです。

私たちはそこに5年以上住んでいましたが、写真で見るよりも、空間で体験する方がはるかに魅力的なのです。ルドルフ・オルジアティの建物を、感覚的に理解するには、その空間を実際に体験することが必要です。多くの家族がそうであるように、子供が生まれると、家の中のスペースは狭くなりますが、私たちのアパートはさらに細分化することができ、私たちは皆、自分の居場所を見つけることができました。もともと2人、あるいは単身用に設計されたアパートで、私たち3人がどのようにうまく共存できるのかを、当事者として体験するのは、とても刺激的でした。建築家としても、多様な使い方ができる空間をデザインすることは、興味深いことだと思います。狭いながらも、心地よい生活感があり、その実験の中で、私たちは楽しく暮らしました。

息子さんは何を覚えていると思いますか?

彼に聞いてみましょう!バシュラールは、生まれ育った家の存在は、私たちの中に記憶を越えて、身体に刻み込まれているものなのだと書いています。私の中にも、いまだに子供の頃に住んでいた家の記憶が残っています。ハウス・チャラーのアパートは、人に根ざした視点を持つ世界を構築しているのです。子供の頃は、何らかの形で、常に家族と接していたいと思うもので、それは知的なものではなく、感情的なものなのです。この小さなアパートは、1つの大きな空間によって作られていて、通りからは少し高い位置にあり、周囲には山々の景色が広がり、床には柔らかいグレーのカーペットが敷かれています。キッチン、バスルーム、ベッドルームといった家庭的な空間は最小限に抑えられ、「大きな空間」が優先されています。良い意味で、巣の中にいるような感覚ですね。

「盾となり、安らぎを与える」ことができる家というコンセプトは、厳しい自然環境から得られる喜びよりも、苦難の方が多いアルプス地方から生まれたのではないかと思っています。ですので、ルドルフ・オルジアティの家は、人間的な身体感覚に、極めて特化しているのです。アルプスの風景において、住宅は厳しい天候や、大気現象、さらには世俗性や余分なものから私たちを守る巣窟なのです。

私たちがこのアパートに住んでいた頃、ハルデンシュタインにある当時の勤務先であった、ピーター・ズントーのアトリエや彼の住宅、そしてチューリッヒにある、クリスチャン・ケレツのフォースター通りのアパートメントなど、ハウス・チャラーとはどこか正反対の性格を持った住宅を体験する機会がありました。これらの住宅は、まったく異なる原理で構想されており、少なくとも私たちにとっては、強い情動を引き起こすものでした。私たちは、独自のルールと矛盾を抱えた世界を構築できる建築に興味があります。個人的な芸術的ヴィジョンを持ち、一時的な流行に左右されることなく、一貫し、変わることのない趣向を持った建築家を高く評価しています。

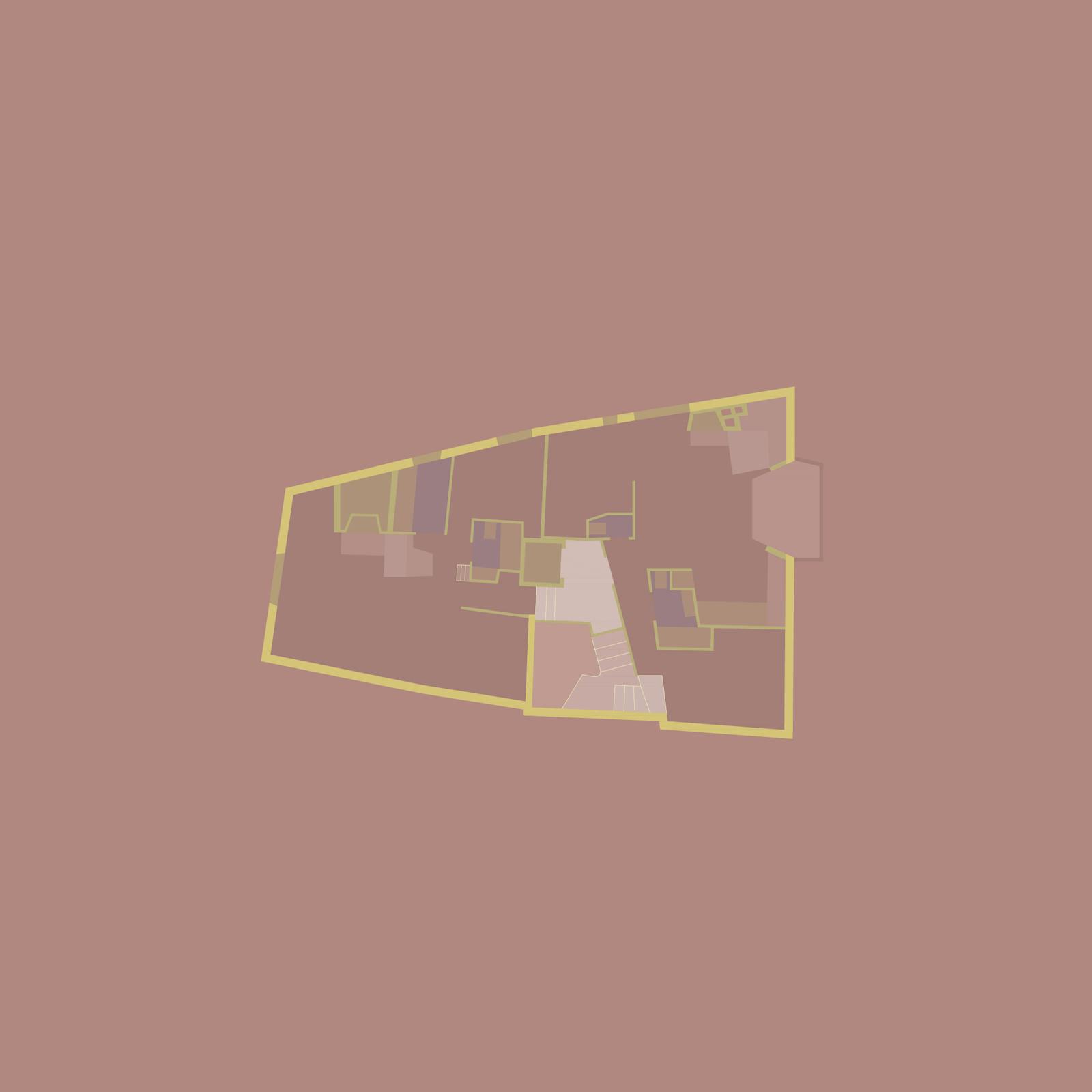

あなたが住んでいたアパートのプランには、メインスペースに1本の柱が立っています。この柱は何のためにあるのでしょうか?

はい。重厚なコンクリートの柱がその場所をはっきりと形作っていますね。それに型枠のテクスチャーが縦のラインを強調しながら、柱の全体形は上部に向かってわずかに先細りになっています。オルジアティは、ギリシャの古典建築から、(構造的なものだけではない)柱の価値を理解していました。彼の建築の多くに見られるように、大きな柱は特定の空間を強調する焦点として使われています。このアパートでは、メインリビングに位置する印象的な柱が、パブリックとプライベートの境界を定義しています。フリムスのラドルフ邸のように、柱と天井の間にある少し奥まった構造部分は、薄い影を落とすには十分なだけオフセットされています。この操作は、小規模な住宅に、ある種のモニュメンタルな雰囲気を与えています。

興味深いのは、このような柱が建物全体に1本しかないことです。

この柱は図面上にも存在しません。その代わり、1階の南側にあるカフェの庭には、2本の太い柱を持つ、大きなアーチ型の開口部からアクセスできるようになっています。建築とは、何を知っているのかではなく、何を見るのかなのです。建築家はこの建物に、私たちが普段見過ごしてしまうような、数多くの特徴をデザインしたのです。平面図を見れば、特定の眺望を強調し、抑揚のある、思いもよらない空間を生み出すために、注意深く構成された幾何学が示されていますが、図面には、空間内での身体の動きを通して、私たちが感じるものは表現されてはいません。ここには、図面には描かれることのない日常のダンスがあって、それは個人的なものですよね。ここでの空間とは、人それぞれ違った動きや関わり方をします。それが心地よいのでしょう。

まだ、建築家が現場で判断していた時代で、それは、人やスケール、そしてタイミングを熟知することで初めて可能になるのです。

工事を行うことは、ただ指示をしたり、規則を守るだけではなく、携わる者同士が理解しあうことでもあったのです。現在では、人々の環境づくりにおける建築家の役割は、以前と比べると二次的なものに過ぎず、私たちはもはや分業化された業務におけるスペシャリストです。指示は驚くほど細かくなり、技術の発展は、超-快適な環境の形成を後押ししてくれるのです。それは、密閉し保護されることでコントロールされた空間によって作られるものなのですが。機械式換気システム、遠隔温度管理、デジタル接続。どういうわけか、私たちは本来の心地よさというものを忘れ、順応性、あるいは順応主義へと移行してしまったのでしょうか?

この建物においては、動線のシステム自体がメインの空間のように思えるのですが。つまり階段が非常によく考えられていますよね。

オルジアティが行った既存の建物への主な操作は、南側ファサードの設計と、垂直の動線計画です。階段は、ある階から別の階への通路である以上に、幾何学的な身体の連なりを生み出す彫刻的なオブジェなのです。そのデザインは、素材と形態の魅力的な並置を特徴としており、連続的に膨らむウールの床は、曲線の幾何学によって強調された真っ白な壁と対照的です。この階段は、曲がりくねった一つの流れであり、人工光源によって遮られる垂直面に沿って、湾曲した形状を作り出しているのです。曲線とは対照的なシャープな直線が、その先にあるアパートの入口へと私たちを誘っています。とても複雑な空間で、広さと狭さ、明るさと暗さ、そして高さと低さの間の張り詰めた空間を体験することになります。

ルドルフ・オルジアティは、地元の骨董品や建物の部品、古い窓、ドア、梁、あらゆる種類の家具の収集家であり、それは、ETHで美術史を専攻した彼の出自と関係しているのかもしれません。おそらく、すべてを元あった場所へと還そうとする試みとして、これらの収集されたものたちをプロジェクトで使用することもありました。

グラウビュンデンという地域には、触覚的で映画的な感覚が感じられます。古い家々が立ち並ぶ谷間には、その土地や、そこに住む人々、そして、そこに建つ建物の間で共有された家具やものが、今でも大事に保管され、使われ続けています。古い洋服ダンス、肘掛け椅子、汚れを落として塗装した古いドアなど、オルジアティはこの家の中で、伝統的なクラフトマンシップを称えるため、そして私たちがこの古い家の中にいることを気付かせてくれる要素として、共同で使用する古い家具をいくつか配置しています。

そうすることで、通りからアパートまでの道のりは長くなりますね。心に残る経験があれば、それは知覚的に、時間を長くするものになります。

その通りです。この階段があれば、アパートまでの道のりがより複雑になり、帰り道はより親しみ深いものになります。新たな動線システムは、建築的にデザインされた中間領域で、アパートを南北軸で分割することで、左右に段差を生み、それにより北側が高くなるので、自然と通りと部屋との間に距離感が生まれます。

オルジアティにとっての官能性とは、感傷や感情といったことに限られたものではなく、ラテン語における「sentire」、つまり気づき、知覚することを意味していました。建物の中から外へと進んでいくときに、手すりの位置が左右で切り替わる決定的な瞬間があるのですが、こうした些細なディテールが、あなたがまさに今パブリックスペースへ足を踏み入れていることをそれとなく気づかせてくれるのです。ハウス・チャラーにおいては、そこでの人の所作を考え抜くことによって、その官能性が獲得されているのだと思います。それがたとえどんな小さなプロジェクトであったとしても、最小限の手法で、記憶に残るような私たちと空間との相互作用をもたらし、そして、美しくも実直な心地よさを私たちに与えてくれたことを思い出させてくれるのです。

2022年10月20日

Giacomo Ortalli: We live in a time of constant movement and exploration. How many of us maintain strong connections to our roots? From a young age we travel, we expand our horizons, we experience new places and cultures: working, touring, studying, it’s possible to quickly arrive at a broad understanding of Europe, and for that matter the wider world, which are obviously very good things; however, there are also consequences; when you move from place to place, it’s easy to lose sight of where you are from and what your actual sense of things is. Perhaps this is true of my own path, nervertheless I am aware of this tension and often return to the words of Mario Merz - “Igloo di Giap” used to describe the perils one faces in battle: “If the enemy masses his forces, he loses ground; if he scatters, he loses strength”.

TODAY, IT’S NOT UNUSUAL FOR AN ARCHITECT TO WORK AND THINK IN NUMEROUS CONTEXTS. TO SOME EXTENT, THE MORE THE MERRIER. WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THIS – IS IT THE ONLY WAY?

More the opposite. Rather than expanding their portfolios of work, some architects opt to remain in a single region and create an architectural vision that is deeply rooted in the local cultural landscape. We are fascinated by these cases.

At the end of his life, Dimitris Pikionis (1887-1968) had the opportunity to intervene in the landscape of Attica, the background and obsession of all his work; he crafted the landscaping works for the archaeological site around the Acropolis in Athens with only local sourced materials and labour. No plans needed - just surveillance and the help of some skilled hands. In another region of the Mediterranean, Alberto Ponis (1933) moved to Palau, Sardegna, and dedicated himself to learning about a given place, thoroughly submerged in a context, a desk full of work, he designed hundreds of houses and realised some unique buildings. In a similar way Geoffrey Bawa (1919-2003) captured the essence of Sri Lanka through its contemporary sensibility.

Much the same, Rudolf Olgiati (1910-1995) was born in Chur, lived and worked in Graubünden his entire life. In the Swiss Alps his work finds its roots. Olgiati mainly built family houses and restored old farmsteads, often working alone, he remained an outsider, even locally he was considered unapproachable. Although his signature was evident, he did not cultivate a style, did not represent a school and did not feel committed to any organisation. This defiladed position gave him the time and the necessary quietness to focus on a strong architectural vision, unperturbed by popular taste. Although Olgiati remained unconcerned with larger arguments or movements, over the years, his studio in Flims did serve as laboratory of thinking and learning for several young architects from the architecture department of the ETH Zurich. Since his death, interest in his buildings has grown, probably to a level greater than during his own lifetime, and his work continues to have lasting influence on the recent generations of Swiss architects.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE HIS WORK?

His built work combines, with great ability, the vernacular traditions of a region and the ethos of a progressive modernism, whilst, above all remaining beautifully sensitive to the alpine landscape. As Peter Märkli noted, he had a rigorous approach to designing small houses as specific nests, formed by constituent elements that cannot be altered and articulated by subtle qualities and details. His houses are independent volumes, often placed in sloping ground, formed by massive white envelopes creating contrasting features, chamfered windows, large openings with specific orientations, sloping mono-pitched stone roofs, tower-like chimneys, arched doors, oversized columns, niches, places full of light, dark corners, all in balance, aspiring to wholeness – a complete work. It is deeply personal work; Olgiati built houses and rooms that he found meaningful and beautiful.

From the interior, rooms are free of symmetrical relationships, shaped to perform for a specific activity; he was not burdened by the modern dogma of „flexible spaces”, that we seem to exclusively contemplate today. On one hand, his work reminded me of Christoph Alexander’s book “A Pattern Language” which elaborates on spatial archetypes, that stem from how people live. Rudolf Olgiati strove to provide responses to common habits and searched for a relationship between architecture and its inhabitants. At the same time, this rootedness to the cultural landscape was subverted by a fascination with ancient Greek architecture and the late sculptural works of Le Corbusier. This conflict creates a kind of tension or even mysticism in his architecture, which is difficult to explain.

His buildings emanate a strong, seemingly independent power. The houses are designed from inside out, from the perspective of the inhabitant as he or she uses each room; the outer form is a consequence. In a way he was quite indifferent to the issue of form and style.

The windows do not respond to exterior geometrical references or axis alignments. You can notice the freedom of placing a large opening on the corner and a small one in the centre within a thick wall and the research of stark contrasts and “chiaroscuro” between shadow and light, a theme which is prevalent in the reveals of Engadin’s massive farmhouses. In this sense we can see an artistic approach in working with volumes with the underlying intention of balancing elements in a unified whole, as a fine sculptor. He was someone who understood presence in form, and the gradations of it.

HOW DID YOU COME TO KNOW HAUS ZSCHALER?

Before founding our own practice, we lived in Chur, working for 8 years at Atelier Peter Zumthor. Haus Zschaler is a prominent residential and commercial building in Chur’s old town, on its north side, an eye-catching 19th century decorated façade, facing Obere Gasse, beautifully restored by the artist Steivan Liun Könz, makes it immediately recognisable. The house was renovated by Rudolf Olgiati in the second half of the 1970’s. He changed the overall circulation, the south side of the building and most of the interiors. On the ground floor, there is a small shop set within a glazed corner and the entrance to a very popular café with a small garden on the south side. Originally, the building contained full-storey flats, Olgiati divided these into eleven small studio flats.

We lived in the loft, under the roof, which in alpine regions, is traditionally dedicated to storage. From the interior, the roof is always an element of memory, with the raw wooden beams in contrast to the smooth white walls. From the window facing northward onto the street below - which on the gable roof is significantly larger than the others - we had a nice view out to the historical townscape. To enter our flat, I had to bow my head because of the low door height. The main room had a sloped double-pitched ceiling with an exceptionally high ridge.

It was like being under a tent with niches and alcoves all around, such as one for sleeping, one for writing, and a small perch for cooking. Everything in that apartment is small, but the spatial richness is beyond any proportion.

Graubünden is a very vital architectural region, and the tradition of craftsmanship is continued in the service of architecture. To this day it remains a holiday destination and there are some benefits to this. Isolation permits an escapism, a lack of perhaps more rigorous questioning, things can be more innocent in a sense, ridded of a learned urbanity, things are freer to be joyful and beautiful on a smaller scale. For instance, a certain pragmatism permitted the southwest façade of Haus Zschaler to be completely cut away and remodeled with angular balconies treated as sculptural elements that cut out the roof like the knuckles of a fist. This radically modern addition is in stark contrast to the historic old town north façade, that remains ornately painted in red, thus preserving the spirit of the historical house and keeping the building in the overall impression of the old town.

We lived there for over 5 years, and it is by far more impressive to experience it spatially than to see it in pictures. To understand Rudolf Olgiati’s building with the senses, one needs to have the real experience of the space. As for many families, with the arrival of our child, the space available in the house reduced, but our apartment allowed a further subdivision, and we all found our place. It was intriguing to witness how we could successfully coexist as 3 in a flat originally designed for two, or less. I think it is interesting, as an architect, to design a space that can be open to diverse uses. Despite the small size, there was a pleasant feeling of living. We lived in that experiment happily.

WHAT DO YOU THINK YOUR SON WILL REMEMBER?

We should ask him! Bachelard wrote that beyond the memory, the native house is physically inscribed in us. I also have this memory connected with the house I lived in as a child. The apartment in Haus Zschaler is also a world, it builds a very human view of the world. As a child, you want to be always in contact with your family, in some way or another. It is an emotional experience, not an intellectual one. The small apartment is made by one big space, high above the street, with views out to the mountains all around and the soft grey carpet on the floor. The more domestic spaces, such as the kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, are reduced to the minimum in favour of the “spazio grande”. The feeling is one of being in a nest, in the best sense of the word.

I believe that the concept of a house which can ‘shield and provide solace’ might originate from the Alps, where hardships are more prevalent than joys derived from outside surroundings. That is why Rudolf Olgiati’s houses are extremely specific to human-oriented bodily senses. In the alpine landscape houses are nests that protect from the outside world, from the severity of the weather and atmospheric phenomena, but also from worldliness and superfluity.

In that same period, we had the occasion to experience other houses, which are somehow the opposite from the apartment we lived in, like Peter Zumthor’s house and atelier where we worked in Haldenstein, as well as Christian Kerez’s Forsterstrasse in Zürich, that we had the opportunity to visit. These houses are conceived with very different principles and provoke strong emotional reactions, at least for us. We are interested in an architecture that is capable of building a world, with its own rules and contradictions. We appreciate architects who develop a personal artistic vision and have a taste which is consistent and stable in time, not altered by temporary fashion.

IN THE FLOOR PLAN OF YOUR APARTMENT THERE IS A SINGLE COLUMN STANDING IN THE MAIN SPACE. WHAT IS THIS COLUMN FOR?

Yes, a massive, concrete column that strikingly sets the scene, the texture of the formwork emphasising the vertical lines and the overall shape slightly tapering towards the top. Olgiati understood the value of not-only-structural columns from Greek classical architecture. As in many of his buildings, large columns were used as focal points to emphasise a specific space. In this specific apartment, such an impressive column situated in the main living space defines the threshold between public and private. Like in the Radulff house in Flims, where the structural part, which is smaller than the column, is pushed back just enough to determine a thin area of shade. This gives the houses a certain monumentality, in relation to the small scale and the domestic program.

IT’S INTERESTING WHY THERE IS ONLY ONE COLUMN OF THIS KIND IN THE ENTIRE BUILDING.

This column is not even present in the plans. Instead, on the ground floor, the garden of the café on the south side is accessible through a large, arched opening marked by two thick columns. Architecture is about what you see, not what you know. The architect designed numerous features in this building of which we remain unaware of. If you to look at the plan, it reveals a carefully composed geometry which is intended to enhance specific views and generate unexpected interior spaces with a continuous tension, but the drawings do not express, what we would feel through the movement in space. Here, there is an undrawn dance to life that is individual, you move and interact differently in these spaces, and it feels good.

It was still during the time when an architect made decisions on site. This is something that occurs when you develop a familiarity with people, scales, and timing.

The construction was not only about instructions and regulations, but an understanding between individuals. Nowadays the role of the architect in building people’s environment is secondary, compared to the past, we are now specialists. Instructions are overwhelmingly elaborated, technological development pushes for hyper-comfort that is achieved with enclosed, protected, and controlled spaces. Mechanical ventilation systems, remote temperature control, digital connectivity. Somehow, we have moved from comfort to conformity, or even conformism?

IT SEEMS THAT THE MAIN SPACE OF THE BUILDING IS THE CIRCULATION SYSTEM - THE VERY ARTICULATED STAIRCASE.

The vertical circulation, together with the southern facade, is Olgiati’s main intervention on the existing building. The staircase is more than a passageway from one level to another, it is a sculptural object which creates a sequence of geometric bodies. Its design features an intriguing juxtaposition of materials and forms: the continuous swelling wool floor contrast with stark white walls highlighted by curved geometries. This stairs winds in a single flow, creating curved shapes along its vertical surfaces that are interrupted by sources of artificial light. The sharp straight lines, in contrast to the curves, invite you to jump into the apartments they lead to. It is a complex space, you experience the spatial tension between narrow and wide, light and dark, high and low.

Rudolf Olgiati was a collector of local antiques and buildings parts; old windows, doors, beams, and furniture of all kinds; it perhaps said something of his original degree in History of Art from the ETH. Sometimes he used these found and recovered elements in projects, perhaps as an attempt to bring everything back to the place of origin.

Graubünden has a tactile cinematic quality. Here, valleys, lined with old houses, hold common furniture and objects that existed through and between the land, its people and their buildings. In house Zschaler, Olgiati placed some pieces of furniture for collective use - an old wardrobe, an armchair, old doors stripped of stain and painted – they are there to celebrate traditional craftsmanship and to point out that we are still in an old house.

SOMEHOW IT MAKES THE WAY FROM THE STREET TO YOUR APARTMENT LONGER. IF YOU HAVE AN EXPERIENCE THAT STAYS IN YOUR MIND, IT PERCEPTUALLY, BECOMES SOMETHING THAT ELONGATES THE TIME.

You’re right. If you have an articulated staircase, the path to reach your apartment is more complex, it enhances the feeling of intimacy on the way home. The new circulation system is an intermediate space which is architecturally designed, which splits the apartments in a North-South axis, and the levels of either side of the building are stepped, with those on the North side being higher, thus further solidifying a sense of disconnection between the street and the flat.

For Olgiati, sensuality was not restricted to sentimentality or feeling but was traced back to the Latin “sentire” for feeling, i.e. sensing and perceiving. As you walk out from the interior of a building to the exterior, there is a distinctive moment when the handrail switches sides. This minor detail offers a subtle reminder that you are entering a public space. In Haus Zschaler, Olgiati captured this with the thoughtful precision of a movement and reminds us that even in a small project, with an economy of means, carefully recording our own interaction with space, affords beauty and an honest comfort.

20.10.2022

我们生活在一个不断流动和探索的时代,例如,我们中有多少人与我们的根源保持紧密联系?我们从小就开始旅行,扩大视野,体验新的地方和文化:工作、旅游、学习,我们有可能很快对欧洲乃至更广阔的世界有一个广泛的了解,这显然是非常好的事情;然而,这也会带来一些后果;当你从一个地方移动到另一个地方时,很容易忘记你来自哪里,你对事物的实际感觉是什么。也许对于我的个人经历也是如此,但我意识到了这种紧张关系,并经常回想起马里奥-梅尔兹(Mario Merz)的名言——他用“伽岗之冰屋”(Igloo di Giap)来形容战斗中面临的危险:“如果敌人集中兵力,他就会失去阵地;如果敌人分散,他就会失去力量。”

今天,建筑师在多种不同的语境下工作和思考已是司空见惯。某种程度上,越多越好。您对此有何看法——这是唯一的方式么?

更多的情况恰恰相反。一些建筑师并没有扩大他们的作品集,而是选择留在一个地区,创造一种深深扎根于当地文化景观的建筑愿景。我们着迷于这些案例。

在他生命的最后阶段,迪米特里斯-皮克奥尼斯(Dimitris Pikionis,1887-1968年)有机会介入阿提卡的景观,这是他所有作品的背景和痴迷之处;他为雅典卫城周围的考古遗址精心设计的景观工程仅使用了当地的材料和劳动力,不需要计划——只需要监督和一些熟练工人的帮助。在地中海的另一个地区,阿尔贝托-波尼斯(Alberto Ponis,1933年)搬到了撒丁岛的帕劳,全身心地投入于学习一个特定的地方,完全融入了语境中,他设计了数百栋住宅,并实现了一些独特的建筑。同样,杰弗里-巴瓦(Geoffrey Bawa,1919-2003)也通过其当代的感性捕捉到了斯里兰卡的精髓。

类似的情况也适用于鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂(1910-1995),他出生于楚尔,一生都在格劳宾登生活和工作。他的作品扎根于瑞士阿尔卑斯山。奥尔贾蒂主要建造家庭住宅和修复古老的农庄,经常独自工作。他一直是个局外人,甚至在当地被认为是难以接近的人。尽管他的个人标签显而易见,但他并没有形成自己的风格,也不代表某个流派,更没有加入任何组织。这种淡化的立场给予他时间和必要的安静,使他能够专注于强烈的建筑理念,不受大众口味的影响。尽管奥尔贾蒂对更大的争论或运动并不关心,但多年来,他在弗利姆斯的工作室确实为苏黎世联邦理工学院建筑系几位年轻建筑师提供了思考和学习的实验场所。自他去世后,人们对他的建筑越来越感兴趣,其程度可能超过了他生前的水平,他的作品依然对新一代的瑞士建筑师产生着持久的影响。

您如何评价他的作品?

他的建筑作品以极高的能力结合了地区的本土传统和进步的现代主义精神,同时,最重要的是对阿尔卑斯山的景观保持着优美的敏感性。正如彼得-马克利(Peter Märkli)所指出的,他以严谨的态度将小型住宅设计为特定的巢穴,这些巢穴由组合元素构成,而这些元素并不以微妙的品质和细节而改变和明确。他的住宅是独立的体量,通常建在倾斜的地面上,由巨大的白色围墙构成,形成鲜明的对比,倒角的窗户,具有特定朝向的大开口,倾斜的单斜石屋顶,塔形烟囱,拱形门,超大的柱子,壁龛,充满光线的地方,阴暗的角落,所有这些都保持平衡,追求整体性——一件完整的作品。这是一件极具个人风格的作品;奥尔贾蒂建造了他认为有意义和美丽的住宅和房间。

从内部看,房间不受对称关系的限制,形态被塑造成适合特定活动的空间;他没有被 “灵活空间 “的现代教条所束缚,而我们今天似乎只考虑这点。一方面,他的作品让我想起克里斯托夫-亚历山大(Christoph Alexander)的著作《模式语言》(A Pattern Language),该书阐述了源于人们生活方式的空间原型。鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂努力对人们的生活习惯做出回应,并寻求建筑与居民之间的关系。与此同时,他对古希腊建筑和勒客柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)的晚期雕塑作品的着迷使他与文化景观的根基产生了冲突。这种冲突在他的建筑中创造了一种张力,甚至是神秘感,难以解释。

他的建筑散发着一种强大而似乎独立的力量。这些住宅是从内到外设计的,从居住者使用每个房间的角度出发;外在形式只是结果。在某种程度上,他对形式和风格问题漠不关心。

窗户不受外部几何参考或轴线对齐的影响。你可以留意到在厚厚的墙体中将一个大的开口放置在角落和一个小的开口放置在中心的自由性,您还可以研究光与影之间的强烈对比和 “明暗对照”,这一主题在恩加丁地区的大型农舍中非常突出。从这个意义上说,我们可以看到他在处理体量时采用了艺术的方法,其基本意图是在一个统一的整体中平衡元素,就像一位优秀的雕塑家一样。他是一个理解形式存在和渐变的人

您是如何知道兹沙勒公寓的?

在成立自己的事务所之前,我们住在楚尔,在彼得客卒母托事务所工作了8年。 兹沙勒公寓作为住宅和商业建筑位于楚尔老城的北侧,其引人注目的19世纪装饰性立面,面向上巷(Obere Gasse),由艺术家斯泰凡客利恩客肯茨(Steivan Liun Könz)精心修复,使其立刻可被辨识。20世纪70年代后半期,鲁道夫-奥尔加蒂对房屋进行了翻修。他改变了建筑的流线、南侧和大部分的室内空间。在底层的玻璃角落里有一个小商店,还有一个非常受欢迎的咖啡馆的入口,咖啡馆的南侧有一个小花园。最初,该建筑包含整层公寓,奥尔贾蒂将其划分为十一个个小型工作室公寓。

我们住在阁楼里,屋顶下方,在阿尔卑斯地区,阁楼传统上是用来储藏物品的。从室内看,屋顶总是令人回味无穷,原始的木梁与光滑的白墙形成鲜明对比。从朝北的窗户可以看到下面的街道——老虎窗比其他窗户要大得多——我们可以欣赏到历史悠久的城市景观。由于门的高度较低,我不得不低头进入我们的公寓。主卧室有一个倾斜的双坡屋顶,屋脊特别高。

就像在一个帐篷里,四周都有壁龛和凹槽,比如一个睡觉的,一个写字的,还有一个做饭的小平台。公寓里的一切都很小,但空间的丰富性却超越了任何比例。

格劳宾登州的建筑业非常活跃,工艺传统在为建筑服务的过程中得到延续。时至今日,格劳宾登仍是一个度假胜地。与世隔绝的环境允许人们逃避现实,缺乏严谨的思考,从某种意义上说,这里的一切都更加纯真,摆脱了学究式的城市化,在更小的范围内,人们可以更加自由地享受快乐和美丽。例如,某种实用主义允许将兹沙勒宅的西南立面完全切掉,并用棱角分明的阳台作为雕塑元素进行改造,这些阳台像拳头的关节一样将屋顶切掉。这种激进的现代加建与历史悠久的老城区北立面形成鲜明对比,北立面仍然被涂上华丽的红色油漆,从而保留了历史住宅的精神,并将该建筑保留在老城区的整体印象中。

我们在那里住了5年多,从空间上体验它比从图片上看到它更令人印象深刻。要从感官上理解鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂的建筑,就需要对空间有真实的体验。和许多家庭一样,随着我们孩子的到来,家里的空间变小了,但我们的公寓可以进一步划分,我们都找到了自己的位置。见证我们如何在一个原本为两个人或更少人设计的公寓里成功地实现三人共处是一件非常有趣的事情。我认为,作为一名建筑师,设计一个可用于多种用途的空间是非常有趣的。尽管面积不大,但却有一种愉快生活的感觉。我们愉快地生活在这个实验中。

您认为您的儿子会记住什么?

我们应该问问他!巴什拉曾写道,在记忆之外,故乡的住宅也在我们的身体上刻下了印记。我也有这样关于童年住宅的记忆。在兹沙勒的公寓也是一个世界,它构建了一种非常人性化的世界观。作为一个孩子,你希望以某种方式与家人保持联系。这是一种情感体验,而不是智力体验。小公寓由一个大空间组成,高高地耸立在街道之上,四周群山环绕,地板上铺着柔软的灰色地毯。厨房、浴室、卧室等更加家居化的空间被减少到最低限度,以让位于“大空间”。 感觉就像这个词的最佳含义,身处于一个巢穴中。

我认为,”遮风挡雨、提供慰藉 “的住宅这一概念可能源自阿尔卑斯山,在那里,艰辛比来自外界环境的欢乐更为普遍。这就是为什么鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂的住宅对于以人为本的身体感官来说是极为具体的。在阿尔卑斯山景观中,住宅是保护人们免受外界恶劣温度和气候现象影响的巢穴,同时也避免世俗和浮华的影响。

在同一时期,我们有机会参观了其他一些与我们所居住的公寓截然相反的住宅,比如彼得-卒母托在哈尔登施泰因(Haldenstein)的住宅和工作室,以及克里斯蒂安-凯瑞兹(Christian Kerez)在苏黎世(Zürich)的福斯特大街(Forsterstrasse)。这些房屋采用了非常不同的原则,引发了强烈的情感反应,至少对我们来说如此。我们对一种能够构建一个拥有自己规则和矛盾的世界的建筑感兴趣。我们欣赏那些能够发展出个人艺术愿景并且在时间上具有一致和稳定品味的建筑师,而不受当下潮流的影响。

在您公寓的平面图中,有一根柱子矗立在主要空间中。这根柱子是为什么呢?

是的,一根巨大的混凝土圆柱营造了瞩目的场景,模板的纹理突出了垂直线条,整体形状向顶部略微收窄。奥尔贾蒂理解了希腊古典建筑中那些不单单是结构性的柱子的价值。在他的许多建筑中,大型圆柱都被用作强调特定空间的焦点。在这套公寓中,一个如此令人印象深刻的柱子位于主要的起居空间,定义了公共与私人之间的门槛。就像在弗利姆斯(Flims)的拉杜尔夫(Radulff)住宅中,比圆柱小的结构部分被向后推,刚好形成一个薄薄的阴影区域。这给予了这些住宅一定的纪念性,与小尺度和家庭功能相呼应。

有趣的是,为什么整座建筑只有一根这样的柱子。

这根柱子甚至没有出现在图纸中。取而代之的是,在底层,咖啡厅南侧的花园可以通过一个巨大的拱形开口进入,开口处有两根粗大的圆柱。建筑是你所看到的,而不是你所知道的。建筑师在这座建筑中设计了许多我们不知道的特点。从平面图上看,我们可以看到一个精心设计的几何图形,其目的是为了增强特定的视图,并产生意想不到的具有持续张力的内部空间,但图纸无法表达出我们通过空间中的移动所感受到的东西。在这里,有一种未被描绘的生活的舞蹈,它是个性化的,你在这些空间中以不同的方式移动与交互,感觉很好。

那还是建筑师在现场做决定的时代,是当你与人们、尺度和时间建立熟悉感时发生的事情。

建筑不仅仅是指令和规定,而是人与人之间的理解。与过去相比,现在建筑师在建造人居环境中的作用是次要的,我们现在是专家。指示变得极其复杂,技术的发展推动了超舒适性的实现,而这种超舒适性是通过封闭、保护和控制的空间来实现的。机械通风系统、远程温度控制、数字连接。不知不觉中,我们已经从舒适走向了顺从,甚至是从众主义?

似乎这栋建筑的主要空间是交通系统——非常清晰的楼梯。

垂直交通和南立面是奥尔贾蒂对现有建筑的主要干预。楼梯不仅仅是从一个楼层到另一个楼层的通道,它还是一个创造几何体序列的雕塑物。它的设计特点是将各种材料和形式并置在一起:连续膨胀的羊毛地板与弧形几何图案突出的白色墙壁形成鲜明对比。楼梯蜿蜒,沿着垂直表面创造出弯曲的形状,直到被人工光源打断。锐利的直线与曲线形成鲜明对比,吸引人们进入它们所通向的公寓。这是一个复杂的空间,您可以体验到狭窄与宽敞、明亮与黑暗、高与低之间的空间张力。

鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂曾是当地古董和建筑构件的收集者,包括旧窗户、旧门、旧横梁和各种家具;这或许反映了他最初在苏黎世联邦理工学院获得的艺术史学位。有时,他会在项目中使用这些找到和修复的元素,或许是为了让一切回归原点。

格劳宾登有一种触手可及的电影质感。这里,峡谷中散布着古老的住宅,保存着贯穿土地、人民和他们的建筑之间的共同家具和物品。在兹沙勒公寓里,奥尔贾蒂摆放了一些供集体使用的家具——一个旧衣柜、一把扶手椅、一扇去掉污渍涂上油漆的旧门——它们的存在是为了颂扬传统工艺,并指出我们仍然在一座老住宅里。+

某种意义上说,它让从街道到你的公寓的路程变得更长了。如果你有一段刻在脑海中的经历,从感知上来说,它会变成延长时间的东西。

您说得对。如果你有一个精心设计的楼梯,到达你的公寓的路径就更加复杂,它增强了回家路上的亲切感。新的交通系统是一个经过建筑设计的中间空间,它在南北轴线上将公寓分隔开来,建筑两侧的楼层也呈阶梯状,北侧的楼层较高,从而进一步巩固了街道与公寓之间的脱节感。

对奥尔贾蒂来说,感性并不局限于感情或感觉,而是可以追溯到拉丁语 “sentire”,即感知和知觉。当您从建筑内部走到外部时,有一个独特的时刻,手扶栏换了边。这个小细节微妙地提醒您正在进入一个公共空间。在兹沙勒公寓中,奥尔贾蒂以细腻而精确的方式捕捉到了这一点,并提醒我们,即使是在一个小项目中,通过经济的手段,仔细记录我们自己与空间的互动,也会带来美和真诚的舒适。

2022年10月20日

私たちは絶え間ない変化と探求の時代に生きています。例えば、自身のルーツと強い結びつきを保っているような人はどれほどいるのでしょうか?私たちは、若い時から旅をしながら視野を広げ、新しい場所や文化を体験してきました。働いたり、観光したりしながら、学んでいくことでヨーロッパ文化を広く理解することができました。そうして世界も同じように理解することができるのだと思いますし、それはとても素晴らしいことだと思います。ところが、弊害も生じます。つまり、転々と場所を移動することで、自分がどこからきたのか、どう物事を理解しているのかを簡単に見失ってしまうのです。私自身もそうだったのかもしれません。ただ、そのことに意識的ではありましたし、マリオ・メルツの作品「ザップのイグルー」に用いられた、戦いの中で直面する危険を表現するために使われた言葉をよく思い出していました。「敵が軍勢を集めれば敗れ、散らせば勢力を失う」。

今日では、建築家が様々な文脈の中で思考し、活動することは普通なことです。むしろ、歓迎されていることではないでしょうか。この状況に関してはどう思われますか?そうあるべきだとお考えですか?

むしろ逆ですね。作品のポートフォリオを広げていくよりも、一つの地域にとどまることで、その地域の文化的景観に深く根ざした建築的思考を創造する、そういったことを選ぶ建築家もいます。私たちはそちらの方が魅力に感じます。

ディミトリス・ピキオニス(1887-1968)は晩年になって、アッティカの風景にのめり込んでいきました。彼の全ての作品はその風景に影響されたものです。アテネのアクロポリス周辺の遺跡のランドスケープをその土地にある素材と労働力だけで作り上げました。プランなど必要ありませんでした。しっかり作業を管理して、あとは熟練工の助けがあればよかったのです。地中海のまた別の地域では、アルベルト・ポニス(1933年)がサルデーニャ島のパラオに移住しています。その土地での学びに全てを捧げ、すっかりと溶け込んでいました。机の上には、何百もの家の設計図が広げられ、いくつかのユニークな建物が実現しています。同じように、ジェフリー・バワ(1919-2003)は、現代的な感覚でスリランカを捉えています。

そして、ルドルフ・オルジアティ(1910-1995)はクールで生まれ、働き、その生涯をグラウビュンデンで過ごしました。彼のルーツはスイスのアルプスの中にあります。オルジアティはファミリー向けの住宅を建てたり、古い農家を修復したりしていたわけですが、一人で仕事していましたし、地元でも近寄りがたい存在であったようです。彼のサインは明白なものですが、スタイルを確立したり、スクールを作ったりするようなことはせず、いかなる組織にも所属しようとしなかった。こうした閉じた環境の中で、大衆の好みに左右されることなく、強靭な建築的ビジョンに集中するための時間と静けさを彼は手に入れていたのです。オルジアティは、大きな議論や運動には無関心ではあったものの、彼のフリムスにあるスタジオは長年に渡って、チューリッヒ工科大学建築学科の若い建築家たちの思考と学習の実験場となっていました。彼の死後、その関心はおそらく生前よりも高まっていて、最近のスイスの建築家たちの世代にも影響を与え続けています。

彼の作品はどういったものなのでしょうか?

彼の作品は、地域の伝統的な風土と進歩的なモダニズムの精神を見事に融合させるとともに、アルプスの風景に対して美しく繊細であり続けています。ピーター・メルクリが述べるには、彼は、小さな住宅を特別な巣窟のようなものとして捉えていて、設計にあたっては厳格なアプローチを持っていたのだと。つまりそれは、変更することができないほどに繊細な質とディテールによって整えられたものであるべきだと。彼の設計した家は、独立したヴォリュームで、しばしば傾斜地に配置され、巨大な白い外壁が対照的な特徴を作り出していて、面取りされた窓、特定の方角への大きな開口、単純な勾配をもった石の屋根、搭状の煙突、アーチ型のドア、大きな柱、ニッチ、光あふれる場所、暗いコーナー、それらすべてを均衡させた全体性を求める、完全な作品なのです。彼の興味や美意識を元に作られる、深く個人的なものでもありますが。

室内から見ると、部屋は対称的な関係から解放され、特定の活動のために形作られています。彼は、現代の私たちがもっぱら考えているような「フレキシブルな空間」というドグマに縛られることはなかったのです。一方で、彼の作品は、人々の暮らしから生まれた空間の原型についてまとめられた、クリストファー・アレグサンダーの著書「パタン・ランゲージ」を思い起こさせます。ルドルフ・オルジアティは、一般的な習慣に対応し、建築とそこに住む人々との関係を模索したのです。それと同時に、古代ギリシャ建築や、ル・コルビュジエの後期彫刻的作品への憧れによって、文化的景観に根ざしたそれまでの態度を改めることになります。この対立が、彼の建築に一種の緊張感、あるいは神秘性を生み出しているのですが、これは説明するのが難しいですね。

一見、彼の建築はとても自律した力強いものに見えます。しかし、住宅は内側から外側へ、各部屋を使う住人の視点から設計されており、外形は結果的なものなのです。ある意味、彼は形やスタイルの問題には無頓着でした。

窓は、ファサードの幾何学的形状や、軸の配置に対応することはありません。大きな開口部を角に設けたり、分厚い壁面の中央に小さな開口部を配置する自由さ。そして、エンガディンの巨大な農家の外観に共通するテーマである、影と光の間の、激しいコントラストと「キアロスクーロ」の探求に気付くでしょう。この意味において、一人の優れた彫刻家としての、統一された全体の中で、各要素を均衡させることを意図したヴォリューム操作に、芸術的なアプローチを見ることができます。彼は、フォルムの存在感や、そのグラデーションを理解している人でした。

ハウス・チャラーをどのようにして知りましたか?

私たちは、自分たちの事務所を設立する以前、クールに住み、アトリエ・ピーター・ズントーで8年間働いていました。 ハウス・チャラーは、クール旧市街の著名な住宅兼商業ビルで、北側のオブレ・ガッセに面した19世紀の装飾が目を引くファサードは、アーティストのシュタイフン・リウン・クンツによって美しく修復されており、それはこの住宅の目印にもなっています。1970年代後半に、ルドルフ・オルジアティがこの家を改築し、全体の動線、建物の南側、そしてインテリアの大部分を変更しました。1階には、ガラス張りのコーナーに小さなショップがあり、南側には小さな庭のある人気のカフェの入り口があります。元々、この建物は一軒のアパートでしたが、オルジアティはこれを、11の小さなワンルームアパートに分割しました。

私たちが住んでいたのは屋根の下のロフト空間で、そこはアルプス地方では伝統的に倉庫として使われていました。室内から見ると、屋根は常に思い出の要素であり、滑らかな白い壁とは対照的に、むき出しの木造梁が見えます。北側の通りに面した窓(切妻屋根で他の窓よりかなり大きい)からは、歴史的な町並みを見渡すことができます。部屋に入るには、ドアの高さが低いので、頭を下げなければなりませんが、メインルームの天井には勾配があり、中央の頂部は非常に高くなっています。

あちこちにニッチやアルコーブがあり、それらは寝床や、書斎、料理用の小さな腰掛けなどになり、まるでテントの下にいるようでした。このアパートにあるものはすべて小さいのですが、空間の豊かさは比類のないものです。

グラウビュンデンは、建築的に非常に重要な地域であり、クラフトマンシップの伝統が建築分野において受け継がれてきています。ここは現在に至るまで、人々の保養地であったわけですが、それにもいくつかの理由があるのでしょう。ここでの孤立的状況は、現実逃避を可能にしてくれます。厳かな問いなどに悩むようなことなどなく、ある意味、純粋な状態でいられますし、体に染み付いた都市的考えからも解放され、小さなスケールの物事に楽しさや美しさを感じることができるのでしょう。例えば、ハウス・チャラーの南西のファサードは、ある種の実用主義によって完全に切り取られるように改築されていて、彫刻的な要素としての角ばったバルコニーが、拳の指の関節のように、屋根を切り取っています。この過激でモダンな増築は、歴史的な旧市街の北側ファサードとは対照的です。北側には、赤い装飾が施された壁面を残すことで、歴史的なこの住宅の精神は保たれたまま、古い町並みの全体的な印象の中に、この建物を残すことができたのです。

私たちはそこに5年以上住んでいましたが、写真で見るよりも、空間で体験する方がはるかに魅力的なのです。ルドルフ・オルジアティの建物を、感覚的に理解するには、その空間を実際に体験することが必要です。多くの家族がそうであるように、子供が生まれると、家の中のスペースは狭くなりますが、私たちのアパートはさらに細分化することができ、私たちは皆、自分の居場所を見つけることができました。もともと2人、あるいは単身用に設計されたアパートで、私たち3人がどのようにうまく共存できるのかを、当事者として体験するのは、とても刺激的でした。建築家としても、多様な使い方ができる空間をデザインすることは、興味深いことだと思います。狭いながらも、心地よい生活感があり、その実験の中で、私たちは楽しく暮らしました。

息子さんは何を覚えていると思いますか?

彼に聞いてみましょう!バシュラールは、生まれ育った家の存在は、私たちの中に記憶を越えて、身体に刻み込まれているものなのだと書いています。私の中にも、いまだに子供の頃に住んでいた家の記憶が残っています。ハウス・チャラーのアパートは、人に根ざした視点を持つ世界を構築しているのです。子供の頃は、何らかの形で、常に家族と接していたいと思うもので、それは知的なものではなく、感情的なものなのです。この小さなアパートは、1つの大きな空間によって作られていて、通りからは少し高い位置にあり、周囲には山々の景色が広がり、床には柔らかいグレーのカーペットが敷かれています。キッチン、バスルーム、ベッドルームといった家庭的な空間は最小限に抑えられ、「大きな空間」が優先されています。良い意味で、巣の中にいるような感覚ですね。

「盾となり、安らぎを与える」ことができる家というコンセプトは、厳しい自然環境から得られる喜びよりも、苦難の方が多いアルプス地方から生まれたのではないかと思っています。ですので、ルドルフ・オルジアティの家は、人間的な身体感覚に、極めて特化しているのです。アルプスの風景において、住宅は厳しい天候や、大気現象、さらには世俗性や余分なものから私たちを守る巣窟なのです。

私たちがこのアパートに住んでいた頃、ハルデンシュタインにある当時の勤務先であった、ピーター・ズントーのアトリエや彼の住宅、そしてチューリッヒにある、クリスチャン・ケレツのフォースター通りのアパートメントなど、ハウス・チャラーとはどこか正反対の性格を持った住宅を体験する機会がありました。これらの住宅は、まったく異なる原理で構想されており、少なくとも私たちにとっては、強い情動を引き起こすものでした。私たちは、独自のルールと矛盾を抱えた世界を構築できる建築に興味があります。個人的な芸術的ヴィジョンを持ち、一時的な流行に左右されることなく、一貫し、変わることのない趣向を持った建築家を高く評価しています。

あなたが住んでいたアパートのプランには、メインスペースに1本の柱が立っています。この柱は何のためにあるのでしょうか?

はい。重厚なコンクリートの柱がその場所をはっきりと形作っていますね。それに型枠のテクスチャーが縦のラインを強調しながら、柱の全体形は上部に向かってわずかに先細りになっています。オルジアティは、ギリシャの古典建築から、(構造的なものだけではない)柱の価値を理解していました。彼の建築の多くに見られるように、大きな柱は特定の空間を強調する焦点として使われています。このアパートでは、メインリビングに位置する印象的な柱が、パブリックとプライベートの境界を定義しています。フリムスのラドルフ邸のように、柱と天井の間にある少し奥まった構造部分は、薄い影を落とすには十分なだけオフセットされています。この操作は、小規模な住宅に、ある種のモニュメンタルな雰囲気を与えています。

興味深いのは、このような柱が建物全体に1本しかないことです。

この柱は図面上にも存在しません。その代わり、1階の南側にあるカフェの庭には、2本の太い柱を持つ、大きなアーチ型の開口部からアクセスできるようになっています。建築とは、何を知っているのかではなく、何を見るのかなのです。建築家はこの建物に、私たちが普段見過ごしてしまうような、数多くの特徴をデザインしたのです。平面図を見れば、特定の眺望を強調し、抑揚のある、思いもよらない空間を生み出すために、注意深く構成された幾何学が示されていますが、図面には、空間内での身体の動きを通して、私たちが感じるものは表現されてはいません。ここには、図面には描かれることのない日常のダンスがあって、それは個人的なものですよね。ここでの空間とは、人それぞれ違った動きや関わり方をします。それが心地よいのでしょう。

まだ、建築家が現場で判断していた時代で、それは、人やスケール、そしてタイミングを熟知することで初めて可能になるのです。

工事を行うことは、ただ指示をしたり、規則を守るだけではなく、携わる者同士が理解しあうことでもあったのです。現在では、人々の環境づくりにおける建築家の役割は、以前と比べると二次的なものに過ぎず、私たちはもはや分業化された業務におけるスペシャリストです。指示は驚くほど細かくなり、技術の発展は、超-快適な環境の形成を後押ししてくれるのです。それは、密閉し保護されることでコントロールされた空間によって作られるものなのですが。機械式換気システム、遠隔温度管理、デジタル接続。どういうわけか、私たちは本来の心地よさというものを忘れ、順応性、あるいは順応主義へと移行してしまったのでしょうか?

この建物においては、動線のシステム自体がメインの空間のように思えるのですが。つまり階段が非常によく考えられていますよね。

オルジアティが行った既存の建物への主な操作は、南側ファサードの設計と、垂直の動線計画です。階段は、ある階から別の階への通路である以上に、幾何学的な身体の連なりを生み出す彫刻的なオブジェなのです。そのデザインは、素材と形態の魅力的な並置を特徴としており、連続的に膨らむウールの床は、曲線の幾何学によって強調された真っ白な壁と対照的です。この階段は、曲がりくねった一つの流れであり、人工光源によって遮られる垂直面に沿って、湾曲した形状を作り出しているのです。曲線とは対照的なシャープな直線が、その先にあるアパートの入口へと私たちを誘っています。とても複雑な空間で、広さと狭さ、明るさと暗さ、そして高さと低さの間の張り詰めた空間を体験することになります。

ルドルフ・オルジアティは、地元の骨董品や建物の部品、古い窓、ドア、梁、あらゆる種類の家具の収集家であり、それは、ETHで美術史を専攻した彼の出自と関係しているのかもしれません。おそらく、すべてを元あった場所へと還そうとする試みとして、これらの収集されたものたちをプロジェクトで使用することもありました。

グラウビュンデンという地域には、触覚的で映画的な感覚が感じられます。古い家々が立ち並ぶ谷間には、その土地や、そこに住む人々、そして、そこに建つ建物の間で共有された家具やものが、今でも大事に保管され、使われ続けています。古い洋服ダンス、肘掛け椅子、汚れを落として塗装した古いドアなど、オルジアティはこの家の中で、伝統的なクラフトマンシップを称えるため、そして私たちがこの古い家の中にいることを気付かせてくれる要素として、共同で使用する古い家具をいくつか配置しています。

そうすることで、通りからアパートまでの道のりは長くなりますね。心に残る経験があれば、それは知覚的に、時間を長くするものになります。

その通りです。この階段があれば、アパートまでの道のりがより複雑になり、帰り道はより親しみ深いものになります。新たな動線システムは、建築的にデザインされた中間領域で、アパートを南北軸で分割することで、左右に段差を生み、それにより北側が高くなるので、自然と通りと部屋との間に距離感が生まれます。

オルジアティにとっての官能性とは、感傷や感情といったことに限られたものではなく、ラテン語における「sentire」、つまり気づき、知覚することを意味していました。建物の中から外へと進んでいくときに、手すりの位置が左右で切り替わる決定的な瞬間があるのですが、こうした些細なディテールが、あなたがまさに今パブリックスペースへ足を踏み入れていることをそれとなく気づかせてくれるのです。ハウス・チャラーにおいては、そこでの人の所作を考え抜くことによって、その官能性が獲得されているのだと思います。それがたとえどんな小さなプロジェクトであったとしても、最小限の手法で、記憶に残るような私たちと空間との相互作用をもたらし、そして、美しくも実直な心地よさを私たちに与えてくれたことを思い出させてくれるのです。

2022年10月20日

Giacomo Ortalli: We live in a time of constant movement and exploration. How many of us maintain strong connections to our roots? From a young age we travel, we expand our horizons, we experience new places and cultures: working, touring, studying, it’s possible to quickly arrive at a broad understanding of Europe, and for that matter the wider world, which are obviously very good things; however, there are also consequences; when you move from place to place, it’s easy to lose sight of where you are from and what your actual sense of things is. Perhaps this is true of my own path, nervertheless I am aware of this tension and often return to the words of Mario Merz - “Igloo di Giap” used to describe the perils one faces in battle: “If the enemy masses his forces, he loses ground; if he scatters, he loses strength”.

TODAY, IT’S NOT UNUSUAL FOR AN ARCHITECT TO WORK AND THINK IN NUMEROUS CONTEXTS. TO SOME EXTENT, THE MORE THE MERRIER. WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THIS – IS IT THE ONLY WAY?

More the opposite. Rather than expanding their portfolios of work, some architects opt to remain in a single region and create an architectural vision that is deeply rooted in the local cultural landscape. We are fascinated by these cases.

At the end of his life, Dimitris Pikionis (1887-1968) had the opportunity to intervene in the landscape of Attica, the background and obsession of all his work; he crafted the landscaping works for the archaeological site around the Acropolis in Athens with only local sourced materials and labour. No plans needed - just surveillance and the help of some skilled hands. In another region of the Mediterranean, Alberto Ponis (1933) moved to Palau, Sardegna, and dedicated himself to learning about a given place, thoroughly submerged in a context, a desk full of work, he designed hundreds of houses and realised some unique buildings. In a similar way Geoffrey Bawa (1919-2003) captured the essence of Sri Lanka through its contemporary sensibility.

Much the same, Rudolf Olgiati (1910-1995) was born in Chur, lived and worked in Graubünden his entire life. In the Swiss Alps his work finds its roots. Olgiati mainly built family houses and restored old farmsteads, often working alone, he remained an outsider, even locally he was considered unapproachable. Although his signature was evident, he did not cultivate a style, did not represent a school and did not feel committed to any organisation. This defiladed position gave him the time and the necessary quietness to focus on a strong architectural vision, unperturbed by popular taste. Although Olgiati remained unconcerned with larger arguments or movements, over the years, his studio in Flims did serve as laboratory of thinking and learning for several young architects from the architecture department of the ETH Zurich. Since his death, interest in his buildings has grown, probably to a level greater than during his own lifetime, and his work continues to have lasting influence on the recent generations of Swiss architects.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE HIS WORK?

His built work combines, with great ability, the vernacular traditions of a region and the ethos of a progressive modernism, whilst, above all remaining beautifully sensitive to the alpine landscape. As Peter Märkli noted, he had a rigorous approach to designing small houses as specific nests, formed by constituent elements that cannot be altered and articulated by subtle qualities and details. His houses are independent volumes, often placed in sloping ground, formed by massive white envelopes creating contrasting features, chamfered windows, large openings with specific orientations, sloping mono-pitched stone roofs, tower-like chimneys, arched doors, oversized columns, niches, places full of light, dark corners, all in balance, aspiring to wholeness – a complete work. It is deeply personal work; Olgiati built houses and rooms that he found meaningful and beautiful.

From the interior, rooms are free of symmetrical relationships, shaped to perform for a specific activity; he was not burdened by the modern dogma of „flexible spaces”, that we seem to exclusively contemplate today. On one hand, his work reminded me of Christoph Alexander’s book “A Pattern Language” which elaborates on spatial archetypes, that stem from how people live. Rudolf Olgiati strove to provide responses to common habits and searched for a relationship between architecture and its inhabitants. At the same time, this rootedness to the cultural landscape was subverted by a fascination with ancient Greek architecture and the late sculptural works of Le Corbusier. This conflict creates a kind of tension or even mysticism in his architecture, which is difficult to explain.

His buildings emanate a strong, seemingly independent power. The houses are designed from inside out, from the perspective of the inhabitant as he or she uses each room; the outer form is a consequence. In a way he was quite indifferent to the issue of form and style.

The windows do not respond to exterior geometrical references or axis alignments. You can notice the freedom of placing a large opening on the corner and a small one in the centre within a thick wall and the research of stark contrasts and “chiaroscuro” between shadow and light, a theme which is prevalent in the reveals of Engadin’s massive farmhouses. In this sense we can see an artistic approach in working with volumes with the underlying intention of balancing elements in a unified whole, as a fine sculptor. He was someone who understood presence in form, and the gradations of it.

HOW DID YOU COME TO KNOW HAUS ZSCHALER?

Before founding our own practice, we lived in Chur, working for 8 years at Atelier Peter Zumthor. Haus Zschaler is a prominent residential and commercial building in Chur’s old town, on its north side, an eye-catching 19th century decorated façade, facing Obere Gasse, beautifully restored by the artist Steivan Liun Könz, makes it immediately recognisable. The house was renovated by Rudolf Olgiati in the second half of the 1970’s. He changed the overall circulation, the south side of the building and most of the interiors. On the ground floor, there is a small shop set within a glazed corner and the entrance to a very popular café with a small garden on the south side. Originally, the building contained full-storey flats, Olgiati divided these into eleven small studio flats.

We lived in the loft, under the roof, which in alpine regions, is traditionally dedicated to storage. From the interior, the roof is always an element of memory, with the raw wooden beams in contrast to the smooth white walls. From the window facing northward onto the street below - which on the gable roof is significantly larger than the others - we had a nice view out to the historical townscape. To enter our flat, I had to bow my head because of the low door height. The main room had a sloped double-pitched ceiling with an exceptionally high ridge.

It was like being under a tent with niches and alcoves all around, such as one for sleeping, one for writing, and a small perch for cooking. Everything in that apartment is small, but the spatial richness is beyond any proportion.

Graubünden is a very vital architectural region, and the tradition of craftsmanship is continued in the service of architecture. To this day it remains a holiday destination and there are some benefits to this. Isolation permits an escapism, a lack of perhaps more rigorous questioning, things can be more innocent in a sense, ridded of a learned urbanity, things are freer to be joyful and beautiful on a smaller scale. For instance, a certain pragmatism permitted the southwest façade of Haus Zschaler to be completely cut away and remodeled with angular balconies treated as sculptural elements that cut out the roof like the knuckles of a fist. This radically modern addition is in stark contrast to the historic old town north façade, that remains ornately painted in red, thus preserving the spirit of the historical house and keeping the building in the overall impression of the old town.

We lived there for over 5 years, and it is by far more impressive to experience it spatially than to see it in pictures. To understand Rudolf Olgiati’s building with the senses, one needs to have the real experience of the space. As for many families, with the arrival of our child, the space available in the house reduced, but our apartment allowed a further subdivision, and we all found our place. It was intriguing to witness how we could successfully coexist as 3 in a flat originally designed for two, or less. I think it is interesting, as an architect, to design a space that can be open to diverse uses. Despite the small size, there was a pleasant feeling of living. We lived in that experiment happily.

WHAT DO YOU THINK YOUR SON WILL REMEMBER?

We should ask him! Bachelard wrote that beyond the memory, the native house is physically inscribed in us. I also have this memory connected with the house I lived in as a child. The apartment in Haus Zschaler is also a world, it builds a very human view of the world. As a child, you want to be always in contact with your family, in some way or another. It is an emotional experience, not an intellectual one. The small apartment is made by one big space, high above the street, with views out to the mountains all around and the soft grey carpet on the floor. The more domestic spaces, such as the kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, are reduced to the minimum in favour of the “spazio grande”. The feeling is one of being in a nest, in the best sense of the word.

I believe that the concept of a house which can ‘shield and provide solace’ might originate from the Alps, where hardships are more prevalent than joys derived from outside surroundings. That is why Rudolf Olgiati’s houses are extremely specific to human-oriented bodily senses. In the alpine landscape houses are nests that protect from the outside world, from the severity of the weather and atmospheric phenomena, but also from worldliness and superfluity.

In that same period, we had the occasion to experience other houses, which are somehow the opposite from the apartment we lived in, like Peter Zumthor’s house and atelier where we worked in Haldenstein, as well as Christian Kerez’s Forsterstrasse in Zürich, that we had the opportunity to visit. These houses are conceived with very different principles and provoke strong emotional reactions, at least for us. We are interested in an architecture that is capable of building a world, with its own rules and contradictions. We appreciate architects who develop a personal artistic vision and have a taste which is consistent and stable in time, not altered by temporary fashion.

IN THE FLOOR PLAN OF YOUR APARTMENT THERE IS A SINGLE COLUMN STANDING IN THE MAIN SPACE. WHAT IS THIS COLUMN FOR?

Yes, a massive, concrete column that strikingly sets the scene, the texture of the formwork emphasising the vertical lines and the overall shape slightly tapering towards the top. Olgiati understood the value of not-only-structural columns from Greek classical architecture. As in many of his buildings, large columns were used as focal points to emphasise a specific space. In this specific apartment, such an impressive column situated in the main living space defines the threshold between public and private. Like in the Radulff house in Flims, where the structural part, which is smaller than the column, is pushed back just enough to determine a thin area of shade. This gives the houses a certain monumentality, in relation to the small scale and the domestic program.

IT’S INTERESTING WHY THERE IS ONLY ONE COLUMN OF THIS KIND IN THE ENTIRE BUILDING.

This column is not even present in the plans. Instead, on the ground floor, the garden of the café on the south side is accessible through a large, arched opening marked by two thick columns. Architecture is about what you see, not what you know. The architect designed numerous features in this building of which we remain unaware of. If you to look at the plan, it reveals a carefully composed geometry which is intended to enhance specific views and generate unexpected interior spaces with a continuous tension, but the drawings do not express, what we would feel through the movement in space. Here, there is an undrawn dance to life that is individual, you move and interact differently in these spaces, and it feels good.

It was still during the time when an architect made decisions on site. This is something that occurs when you develop a familiarity with people, scales, and timing.

The construction was not only about instructions and regulations, but an understanding between individuals. Nowadays the role of the architect in building people’s environment is secondary, compared to the past, we are now specialists. Instructions are overwhelmingly elaborated, technological development pushes for hyper-comfort that is achieved with enclosed, protected, and controlled spaces. Mechanical ventilation systems, remote temperature control, digital connectivity. Somehow, we have moved from comfort to conformity, or even conformism?

IT SEEMS THAT THE MAIN SPACE OF THE BUILDING IS THE CIRCULATION SYSTEM - THE VERY ARTICULATED STAIRCASE.

The vertical circulation, together with the southern facade, is Olgiati’s main intervention on the existing building. The staircase is more than a passageway from one level to another, it is a sculptural object which creates a sequence of geometric bodies. Its design features an intriguing juxtaposition of materials and forms: the continuous swelling wool floor contrast with stark white walls highlighted by curved geometries. This stairs winds in a single flow, creating curved shapes along its vertical surfaces that are interrupted by sources of artificial light. The sharp straight lines, in contrast to the curves, invite you to jump into the apartments they lead to. It is a complex space, you experience the spatial tension between narrow and wide, light and dark, high and low.

Rudolf Olgiati was a collector of local antiques and buildings parts; old windows, doors, beams, and furniture of all kinds; it perhaps said something of his original degree in History of Art from the ETH. Sometimes he used these found and recovered elements in projects, perhaps as an attempt to bring everything back to the place of origin.

Graubünden has a tactile cinematic quality. Here, valleys, lined with old houses, hold common furniture and objects that existed through and between the land, its people and their buildings. In house Zschaler, Olgiati placed some pieces of furniture for collective use - an old wardrobe, an armchair, old doors stripped of stain and painted – they are there to celebrate traditional craftsmanship and to point out that we are still in an old house.

SOMEHOW IT MAKES THE WAY FROM THE STREET TO YOUR APARTMENT LONGER. IF YOU HAVE AN EXPERIENCE THAT STAYS IN YOUR MIND, IT PERCEPTUALLY, BECOMES SOMETHING THAT ELONGATES THE TIME.

You’re right. If you have an articulated staircase, the path to reach your apartment is more complex, it enhances the feeling of intimacy on the way home. The new circulation system is an intermediate space which is architecturally designed, which splits the apartments in a North-South axis, and the levels of either side of the building are stepped, with those on the North side being higher, thus further solidifying a sense of disconnection between the street and the flat.

For Olgiati, sensuality was not restricted to sentimentality or feeling but was traced back to the Latin “sentire” for feeling, i.e. sensing and perceiving. As you walk out from the interior of a building to the exterior, there is a distinctive moment when the handrail switches sides. This minor detail offers a subtle reminder that you are entering a public space. In Haus Zschaler, Olgiati captured this with the thoughtful precision of a movement and reminds us that even in a small project, with an economy of means, carefully recording our own interaction with space, affords beauty and an honest comfort.

20.10.2022

我们生活在一个不断流动和探索的时代,例如,我们中有多少人与我们的根源保持紧密联系?我们从小就开始旅行,扩大视野,体验新的地方和文化:工作、旅游、学习,我们有可能很快对欧洲乃至更广阔的世界有一个广泛的了解,这显然是非常好的事情;然而,这也会带来一些后果;当你从一个地方移动到另一个地方时,很容易忘记你来自哪里,你对事物的实际感觉是什么。也许对于我的个人经历也是如此,但我意识到了这种紧张关系,并经常回想起马里奥-梅尔兹(Mario Merz)的名言——他用“伽岗之冰屋”(Igloo di Giap)来形容战斗中面临的危险:“如果敌人集中兵力,他就会失去阵地;如果敌人分散,他就会失去力量。”

今天,建筑师在多种不同的语境下工作和思考已是司空见惯。某种程度上,越多越好。您对此有何看法——这是唯一的方式么?

更多的情况恰恰相反。一些建筑师并没有扩大他们的作品集,而是选择留在一个地区,创造一种深深扎根于当地文化景观的建筑愿景。我们着迷于这些案例。

在他生命的最后阶段,迪米特里斯-皮克奥尼斯(Dimitris Pikionis,1887-1968年)有机会介入阿提卡的景观,这是他所有作品的背景和痴迷之处;他为雅典卫城周围的考古遗址精心设计的景观工程仅使用了当地的材料和劳动力,不需要计划——只需要监督和一些熟练工人的帮助。在地中海的另一个地区,阿尔贝托-波尼斯(Alberto Ponis,1933年)搬到了撒丁岛的帕劳,全身心地投入于学习一个特定的地方,完全融入了语境中,他设计了数百栋住宅,并实现了一些独特的建筑。同样,杰弗里-巴瓦(Geoffrey Bawa,1919-2003)也通过其当代的感性捕捉到了斯里兰卡的精髓。

类似的情况也适用于鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂(1910-1995),他出生于楚尔,一生都在格劳宾登生活和工作。他的作品扎根于瑞士阿尔卑斯山。奥尔贾蒂主要建造家庭住宅和修复古老的农庄,经常独自工作。他一直是个局外人,甚至在当地被认为是难以接近的人。尽管他的个人标签显而易见,但他并没有形成自己的风格,也不代表某个流派,更没有加入任何组织。这种淡化的立场给予他时间和必要的安静,使他能够专注于强烈的建筑理念,不受大众口味的影响。尽管奥尔贾蒂对更大的争论或运动并不关心,但多年来,他在弗利姆斯的工作室确实为苏黎世联邦理工学院建筑系几位年轻建筑师提供了思考和学习的实验场所。自他去世后,人们对他的建筑越来越感兴趣,其程度可能超过了他生前的水平,他的作品依然对新一代的瑞士建筑师产生着持久的影响。

您如何评价他的作品?

他的建筑作品以极高的能力结合了地区的本土传统和进步的现代主义精神,同时,最重要的是对阿尔卑斯山的景观保持着优美的敏感性。正如彼得-马克利(Peter Märkli)所指出的,他以严谨的态度将小型住宅设计为特定的巢穴,这些巢穴由组合元素构成,而这些元素并不以微妙的品质和细节而改变和明确。他的住宅是独立的体量,通常建在倾斜的地面上,由巨大的白色围墙构成,形成鲜明的对比,倒角的窗户,具有特定朝向的大开口,倾斜的单斜石屋顶,塔形烟囱,拱形门,超大的柱子,壁龛,充满光线的地方,阴暗的角落,所有这些都保持平衡,追求整体性——一件完整的作品。这是一件极具个人风格的作品;奥尔贾蒂建造了他认为有意义和美丽的住宅和房间。

从内部看,房间不受对称关系的限制,形态被塑造成适合特定活动的空间;他没有被 “灵活空间 “的现代教条所束缚,而我们今天似乎只考虑这点。一方面,他的作品让我想起克里斯托夫-亚历山大(Christoph Alexander)的著作《模式语言》(A Pattern Language),该书阐述了源于人们生活方式的空间原型。鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂努力对人们的生活习惯做出回应,并寻求建筑与居民之间的关系。与此同时,他对古希腊建筑和勒客柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)的晚期雕塑作品的着迷使他与文化景观的根基产生了冲突。这种冲突在他的建筑中创造了一种张力,甚至是神秘感,难以解释。

他的建筑散发着一种强大而似乎独立的力量。这些住宅是从内到外设计的,从居住者使用每个房间的角度出发;外在形式只是结果。在某种程度上,他对形式和风格问题漠不关心。

窗户不受外部几何参考或轴线对齐的影响。你可以留意到在厚厚的墙体中将一个大的开口放置在角落和一个小的开口放置在中心的自由性,您还可以研究光与影之间的强烈对比和 “明暗对照”,这一主题在恩加丁地区的大型农舍中非常突出。从这个意义上说,我们可以看到他在处理体量时采用了艺术的方法,其基本意图是在一个统一的整体中平衡元素,就像一位优秀的雕塑家一样。他是一个理解形式存在和渐变的人

您是如何知道兹沙勒公寓的?

在成立自己的事务所之前,我们住在楚尔,在彼得客卒母托事务所工作了8年。 兹沙勒公寓作为住宅和商业建筑位于楚尔老城的北侧,其引人注目的19世纪装饰性立面,面向上巷(Obere Gasse),由艺术家斯泰凡客利恩客肯茨(Steivan Liun Könz)精心修复,使其立刻可被辨识。20世纪70年代后半期,鲁道夫-奥尔加蒂对房屋进行了翻修。他改变了建筑的流线、南侧和大部分的室内空间。在底层的玻璃角落里有一个小商店,还有一个非常受欢迎的咖啡馆的入口,咖啡馆的南侧有一个小花园。最初,该建筑包含整层公寓,奥尔贾蒂将其划分为十一个个小型工作室公寓。

我们住在阁楼里,屋顶下方,在阿尔卑斯地区,阁楼传统上是用来储藏物品的。从室内看,屋顶总是令人回味无穷,原始的木梁与光滑的白墙形成鲜明对比。从朝北的窗户可以看到下面的街道——老虎窗比其他窗户要大得多——我们可以欣赏到历史悠久的城市景观。由于门的高度较低,我不得不低头进入我们的公寓。主卧室有一个倾斜的双坡屋顶,屋脊特别高。

就像在一个帐篷里,四周都有壁龛和凹槽,比如一个睡觉的,一个写字的,还有一个做饭的小平台。公寓里的一切都很小,但空间的丰富性却超越了任何比例。

格劳宾登州的建筑业非常活跃,工艺传统在为建筑服务的过程中得到延续。时至今日,格劳宾登仍是一个度假胜地。与世隔绝的环境允许人们逃避现实,缺乏严谨的思考,从某种意义上说,这里的一切都更加纯真,摆脱了学究式的城市化,在更小的范围内,人们可以更加自由地享受快乐和美丽。例如,某种实用主义允许将兹沙勒宅的西南立面完全切掉,并用棱角分明的阳台作为雕塑元素进行改造,这些阳台像拳头的关节一样将屋顶切掉。这种激进的现代加建与历史悠久的老城区北立面形成鲜明对比,北立面仍然被涂上华丽的红色油漆,从而保留了历史住宅的精神,并将该建筑保留在老城区的整体印象中。

我们在那里住了5年多,从空间上体验它比从图片上看到它更令人印象深刻。要从感官上理解鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂的建筑,就需要对空间有真实的体验。和许多家庭一样,随着我们孩子的到来,家里的空间变小了,但我们的公寓可以进一步划分,我们都找到了自己的位置。见证我们如何在一个原本为两个人或更少人设计的公寓里成功地实现三人共处是一件非常有趣的事情。我认为,作为一名建筑师,设计一个可用于多种用途的空间是非常有趣的。尽管面积不大,但却有一种愉快生活的感觉。我们愉快地生活在这个实验中。

您认为您的儿子会记住什么?

我们应该问问他!巴什拉曾写道,在记忆之外,故乡的住宅也在我们的身体上刻下了印记。我也有这样关于童年住宅的记忆。在兹沙勒的公寓也是一个世界,它构建了一种非常人性化的世界观。作为一个孩子,你希望以某种方式与家人保持联系。这是一种情感体验,而不是智力体验。小公寓由一个大空间组成,高高地耸立在街道之上,四周群山环绕,地板上铺着柔软的灰色地毯。厨房、浴室、卧室等更加家居化的空间被减少到最低限度,以让位于“大空间”。 感觉就像这个词的最佳含义,身处于一个巢穴中。

我认为,”遮风挡雨、提供慰藉 “的住宅这一概念可能源自阿尔卑斯山,在那里,艰辛比来自外界环境的欢乐更为普遍。这就是为什么鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂的住宅对于以人为本的身体感官来说是极为具体的。在阿尔卑斯山景观中,住宅是保护人们免受外界恶劣温度和气候现象影响的巢穴,同时也避免世俗和浮华的影响。

在同一时期,我们有机会参观了其他一些与我们所居住的公寓截然相反的住宅,比如彼得-卒母托在哈尔登施泰因(Haldenstein)的住宅和工作室,以及克里斯蒂安-凯瑞兹(Christian Kerez)在苏黎世(Zürich)的福斯特大街(Forsterstrasse)。这些房屋采用了非常不同的原则,引发了强烈的情感反应,至少对我们来说如此。我们对一种能够构建一个拥有自己规则和矛盾的世界的建筑感兴趣。我们欣赏那些能够发展出个人艺术愿景并且在时间上具有一致和稳定品味的建筑师,而不受当下潮流的影响。

在您公寓的平面图中,有一根柱子矗立在主要空间中。这根柱子是为什么呢?

是的,一根巨大的混凝土圆柱营造了瞩目的场景,模板的纹理突出了垂直线条,整体形状向顶部略微收窄。奥尔贾蒂理解了希腊古典建筑中那些不单单是结构性的柱子的价值。在他的许多建筑中,大型圆柱都被用作强调特定空间的焦点。在这套公寓中,一个如此令人印象深刻的柱子位于主要的起居空间,定义了公共与私人之间的门槛。就像在弗利姆斯(Flims)的拉杜尔夫(Radulff)住宅中,比圆柱小的结构部分被向后推,刚好形成一个薄薄的阴影区域。这给予了这些住宅一定的纪念性,与小尺度和家庭功能相呼应。

有趣的是,为什么整座建筑只有一根这样的柱子。

这根柱子甚至没有出现在图纸中。取而代之的是,在底层,咖啡厅南侧的花园可以通过一个巨大的拱形开口进入,开口处有两根粗大的圆柱。建筑是你所看到的,而不是你所知道的。建筑师在这座建筑中设计了许多我们不知道的特点。从平面图上看,我们可以看到一个精心设计的几何图形,其目的是为了增强特定的视图,并产生意想不到的具有持续张力的内部空间,但图纸无法表达出我们通过空间中的移动所感受到的东西。在这里,有一种未被描绘的生活的舞蹈,它是个性化的,你在这些空间中以不同的方式移动与交互,感觉很好。

那还是建筑师在现场做决定的时代,是当你与人们、尺度和时间建立熟悉感时发生的事情。

建筑不仅仅是指令和规定,而是人与人之间的理解。与过去相比,现在建筑师在建造人居环境中的作用是次要的,我们现在是专家。指示变得极其复杂,技术的发展推动了超舒适性的实现,而这种超舒适性是通过封闭、保护和控制的空间来实现的。机械通风系统、远程温度控制、数字连接。不知不觉中,我们已经从舒适走向了顺从,甚至是从众主义?

似乎这栋建筑的主要空间是交通系统——非常清晰的楼梯。

垂直交通和南立面是奥尔贾蒂对现有建筑的主要干预。楼梯不仅仅是从一个楼层到另一个楼层的通道,它还是一个创造几何体序列的雕塑物。它的设计特点是将各种材料和形式并置在一起:连续膨胀的羊毛地板与弧形几何图案突出的白色墙壁形成鲜明对比。楼梯蜿蜒,沿着垂直表面创造出弯曲的形状,直到被人工光源打断。锐利的直线与曲线形成鲜明对比,吸引人们进入它们所通向的公寓。这是一个复杂的空间,您可以体验到狭窄与宽敞、明亮与黑暗、高与低之间的空间张力。

鲁道夫-奥尔贾蒂曾是当地古董和建筑构件的收集者,包括旧窗户、旧门、旧横梁和各种家具;这或许反映了他最初在苏黎世联邦理工学院获得的艺术史学位。有时,他会在项目中使用这些找到和修复的元素,或许是为了让一切回归原点。

格劳宾登有一种触手可及的电影质感。这里,峡谷中散布着古老的住宅,保存着贯穿土地、人民和他们的建筑之间的共同家具和物品。在兹沙勒公寓里,奥尔贾蒂摆放了一些供集体使用的家具——一个旧衣柜、一把扶手椅、一扇去掉污渍涂上油漆的旧门——它们的存在是为了颂扬传统工艺,并指出我们仍然在一座老住宅里。+

某种意义上说,它让从街道到你的公寓的路程变得更长了。如果你有一段刻在脑海中的经历,从感知上来说,它会变成延长时间的东西。

您说得对。如果你有一个精心设计的楼梯,到达你的公寓的路径就更加复杂,它增强了回家路上的亲切感。新的交通系统是一个经过建筑设计的中间空间,它在南北轴线上将公寓分隔开来,建筑两侧的楼层也呈阶梯状,北侧的楼层较高,从而进一步巩固了街道与公寓之间的脱节感。

对奥尔贾蒂来说,感性并不局限于感情或感觉,而是可以追溯到拉丁语 “sentire”,即感知和知觉。当您从建筑内部走到外部时,有一个独特的时刻,手扶栏换了边。这个小细节微妙地提醒您正在进入一个公共空间。在兹沙勒公寓中,奥尔贾蒂以细腻而精确的方式捕捉到了这一点,并提醒我们,即使是在一个小项目中,通过经济的手段,仔细记录我们自己与空间的互动,也会带来美和真诚的舒适。

2022年10月20日

私たちは絶え間ない変化と探求の時代に生きています。例えば、自身のルーツと強い結びつきを保っているような人はどれほどいるのでしょうか?私たちは、若い時から旅をしながら視野を広げ、新しい場所や文化を体験してきました。働いたり、観光したりしながら、学んでいくことでヨーロッパ文化を広く理解することができました。そうして世界も同じように理解することができるのだと思いますし、それはとても素晴らしいことだと思います。ところが、弊害も生じます。つまり、転々と場所を移動することで、自分がどこからきたのか、どう物事を理解しているのかを簡単に見失ってしまうのです。私自身もそうだったのかもしれません。ただ、そのことに意識的ではありましたし、マリオ・メルツの作品「ザップのイグルー」に用いられた、戦いの中で直面する危険を表現するために使われた言葉をよく思い出していました。「敵が軍勢を集めれば敗れ、散らせば勢力を失う」。

今日では、建築家が様々な文脈の中で思考し、活動することは普通なことです。むしろ、歓迎されていることではないでしょうか。この状況に関してはどう思われますか?そうあるべきだとお考えですか?

むしろ逆ですね。作品のポートフォリオを広げていくよりも、一つの地域にとどまることで、その地域の文化的景観に深く根ざした建築的思考を創造する、そういったことを選ぶ建築家もいます。私たちはそちらの方が魅力に感じます。

ディミトリス・ピキオニス(1887-1968)は晩年になって、アッティカの風景にのめり込んでいきました。彼の全ての作品はその風景に影響されたものです。アテネのアクロポリス周辺の遺跡のランドスケープをその土地にある素材と労働力だけで作り上げました。プランなど必要ありませんでした。しっかり作業を管理して、あとは熟練工の助けがあればよかったのです。地中海のまた別の地域では、アルベルト・ポニス(1933年)がサルデーニャ島のパラオに移住しています。その土地での学びに全てを捧げ、すっかりと溶け込んでいました。机の上には、何百もの家の設計図が広げられ、いくつかのユニークな建物が実現しています。同じように、ジェフリー・バワ(1919-2003)は、現代的な感覚でスリランカを捉えています。

そして、ルドルフ・オルジアティ(1910-1995)はクールで生まれ、働き、その生涯をグラウビュンデンで過ごしました。彼のルーツはスイスのアルプスの中にあります。オルジアティはファミリー向けの住宅を建てたり、古い農家を修復したりしていたわけですが、一人で仕事していましたし、地元でも近寄りがたい存在であったようです。彼のサインは明白なものですが、スタイルを確立したり、スクールを作ったりするようなことはせず、いかなる組織にも所属しようとしなかった。こうした閉じた環境の中で、大衆の好みに左右されることなく、強靭な建築的ビジョンに集中するための時間と静けさを彼は手に入れていたのです。オルジアティは、大きな議論や運動には無関心ではあったものの、彼のフリムスにあるスタジオは長年に渡って、チューリッヒ工科大学建築学科の若い建築家たちの思考と学習の実験場となっていました。彼の死後、その関心はおそらく生前よりも高まっていて、最近のスイスの建築家たちの世代にも影響を与え続けています。

彼の作品はどういったものなのでしょうか?

彼の作品は、地域の伝統的な風土と進歩的なモダニズムの精神を見事に融合させるとともに、アルプスの風景に対して美しく繊細であり続けています。ピーター・メルクリが述べるには、彼は、小さな住宅を特別な巣窟のようなものとして捉えていて、設計にあたっては厳格なアプローチを持っていたのだと。つまりそれは、変更することができないほどに繊細な質とディテールによって整えられたものであるべきだと。彼の設計した家は、独立したヴォリュームで、しばしば傾斜地に配置され、巨大な白い外壁が対照的な特徴を作り出していて、面取りされた窓、特定の方角への大きな開口、単純な勾配をもった石の屋根、搭状の煙突、アーチ型のドア、大きな柱、ニッチ、光あふれる場所、暗いコーナー、それらすべてを均衡させた全体性を求める、完全な作品なのです。彼の興味や美意識を元に作られる、深く個人的なものでもありますが。

室内から見ると、部屋は対称的な関係から解放され、特定の活動のために形作られています。彼は、現代の私たちがもっぱら考えているような「フレキシブルな空間」というドグマに縛られることはなかったのです。一方で、彼の作品は、人々の暮らしから生まれた空間の原型についてまとめられた、クリストファー・アレグサンダーの著書「パタン・ランゲージ」を思い起こさせます。ルドルフ・オルジアティは、一般的な習慣に対応し、建築とそこに住む人々との関係を模索したのです。それと同時に、古代ギリシャ建築や、ル・コルビュジエの後期彫刻的作品への憧れによって、文化的景観に根ざしたそれまでの態度を改めることになります。この対立が、彼の建築に一種の緊張感、あるいは神秘性を生み出しているのですが、これは説明するのが難しいですね。

一見、彼の建築はとても自律した力強いものに見えます。しかし、住宅は内側から外側へ、各部屋を使う住人の視点から設計されており、外形は結果的なものなのです。ある意味、彼は形やスタイルの問題には無頓着でした。

窓は、ファサードの幾何学的形状や、軸の配置に対応することはありません。大きな開口部を角に設けたり、分厚い壁面の中央に小さな開口部を配置する自由さ。そして、エンガディンの巨大な農家の外観に共通するテーマである、影と光の間の、激しいコントラストと「キアロスクーロ」の探求に気付くでしょう。この意味において、一人の優れた彫刻家としての、統一された全体の中で、各要素を均衡させることを意図したヴォリューム操作に、芸術的なアプローチを見ることができます。彼は、フォルムの存在感や、そのグラデーションを理解している人でした。

ハウス・チャラーをどのようにして知りましたか?

私たちは、自分たちの事務所を設立する以前、クールに住み、アトリエ・ピーター・ズントーで8年間働いていました。 ハウス・チャラーは、クール旧市街の著名な住宅兼商業ビルで、北側のオブレ・ガッセに面した19世紀の装飾が目を引くファサードは、アーティストのシュタイフン・リウン・クンツによって美しく修復されており、それはこの住宅の目印にもなっています。1970年代後半に、ルドルフ・オルジアティがこの家を改築し、全体の動線、建物の南側、そしてインテリアの大部分を変更しました。1階には、ガラス張りのコーナーに小さなショップがあり、南側には小さな庭のある人気のカフェの入り口があります。元々、この建物は一軒のアパートでしたが、オルジアティはこれを、11の小さなワンルームアパートに分割しました。

私たちが住んでいたのは屋根の下のロフト空間で、そこはアルプス地方では伝統的に倉庫として使われていました。室内から見ると、屋根は常に思い出の要素であり、滑らかな白い壁とは対照的に、むき出しの木造梁が見えます。北側の通りに面した窓(切妻屋根で他の窓よりかなり大きい)からは、歴史的な町並みを見渡すことができます。部屋に入るには、ドアの高さが低いので、頭を下げなければなりませんが、メインルームの天井には勾配があり、中央の頂部は非常に高くなっています。

あちこちにニッチやアルコーブがあり、それらは寝床や、書斎、料理用の小さな腰掛けなどになり、まるでテントの下にいるようでした。このアパートにあるものはすべて小さいのですが、空間の豊かさは比類のないものです。

グラウビュンデンは、建築的に非常に重要な地域であり、クラフトマンシップの伝統が建築分野において受け継がれてきています。ここは現在に至るまで、人々の保養地であったわけですが、それにもいくつかの理由があるのでしょう。ここでの孤立的状況は、現実逃避を可能にしてくれます。厳かな問いなどに悩むようなことなどなく、ある意味、純粋な状態でいられますし、体に染み付いた都市的考えからも解放され、小さなスケールの物事に楽しさや美しさを感じることができるのでしょう。例えば、ハウス・チャラーの南西のファサードは、ある種の実用主義によって完全に切り取られるように改築されていて、彫刻的な要素としての角ばったバルコニーが、拳の指の関節のように、屋根を切り取っています。この過激でモダンな増築は、歴史的な旧市街の北側ファサードとは対照的です。北側には、赤い装飾が施された壁面を残すことで、歴史的なこの住宅の精神は保たれたまま、古い町並みの全体的な印象の中に、この建物を残すことができたのです。

私たちはそこに5年以上住んでいましたが、写真で見るよりも、空間で体験する方がはるかに魅力的なのです。ルドルフ・オルジアティの建物を、感覚的に理解するには、その空間を実際に体験することが必要です。多くの家族がそうであるように、子供が生まれると、家の中のスペースは狭くなりますが、私たちのアパートはさらに細分化することができ、私たちは皆、自分の居場所を見つけることができました。もともと2人、あるいは単身用に設計されたアパートで、私たち3人がどのようにうまく共存できるのかを、当事者として体験するのは、とても刺激的でした。建築家としても、多様な使い方ができる空間をデザインすることは、興味深いことだと思います。狭いながらも、心地よい生活感があり、その実験の中で、私たちは楽しく暮らしました。

息子さんは何を覚えていると思いますか?

彼に聞いてみましょう!バシュラールは、生まれ育った家の存在は、私たちの中に記憶を越えて、身体に刻み込まれているものなのだと書いています。私の中にも、いまだに子供の頃に住んでいた家の記憶が残っています。ハウス・チャラーのアパートは、人に根ざした視点を持つ世界を構築しているのです。子供の頃は、何らかの形で、常に家族と接していたいと思うもので、それは知的なものではなく、感情的なものなのです。この小さなアパートは、1つの大きな空間によって作られていて、通りからは少し高い位置にあり、周囲には山々の景色が広がり、床には柔らかいグレーのカーペットが敷かれています。キッチン、バスルーム、ベッドルームといった家庭的な空間は最小限に抑えられ、「大きな空間」が優先されています。良い意味で、巣の中にいるような感覚ですね。

「盾となり、安らぎを与える」ことができる家というコンセプトは、厳しい自然環境から得られる喜びよりも、苦難の方が多いアルプス地方から生まれたのではないかと思っています。ですので、ルドルフ・オルジアティの家は、人間的な身体感覚に、極めて特化しているのです。アルプスの風景において、住宅は厳しい天候や、大気現象、さらには世俗性や余分なものから私たちを守る巣窟なのです。

私たちがこのアパートに住んでいた頃、ハルデンシュタインにある当時の勤務先であった、ピーター・ズントーのアトリエや彼の住宅、そしてチューリッヒにある、クリスチャン・ケレツのフォースター通りのアパートメントなど、ハウス・チャラーとはどこか正反対の性格を持った住宅を体験する機会がありました。これらの住宅は、まったく異なる原理で構想されており、少なくとも私たちにとっては、強い情動を引き起こすものでした。私たちは、独自のルールと矛盾を抱えた世界を構築できる建築に興味があります。個人的な芸術的ヴィジョンを持ち、一時的な流行に左右されることなく、一貫し、変わることのない趣向を持った建築家を高く評価しています。

あなたが住んでいたアパートのプランには、メインスペースに1本の柱が立っています。この柱は何のためにあるのでしょうか?

はい。重厚なコンクリートの柱がその場所をはっきりと形作っていますね。それに型枠のテクスチャーが縦のラインを強調しながら、柱の全体形は上部に向かってわずかに先細りになっています。オルジアティは、ギリシャの古典建築から、(構造的なものだけではない)柱の価値を理解していました。彼の建築の多くに見られるように、大きな柱は特定の空間を強調する焦点として使われています。このアパートでは、メインリビングに位置する印象的な柱が、パブリックとプライベートの境界を定義しています。フリムスのラドルフ邸のように、柱と天井の間にある少し奥まった構造部分は、薄い影を落とすには十分なだけオフセットされています。この操作は、小規模な住宅に、ある種のモニュメンタルな雰囲気を与えています。

興味深いのは、このような柱が建物全体に1本しかないことです。

この柱は図面上にも存在しません。その代わり、1階の南側にあるカフェの庭には、2本の太い柱を持つ、大きなアーチ型の開口部からアクセスできるようになっています。建築とは、何を知っているのかではなく、何を見るのかなのです。建築家はこの建物に、私たちが普段見過ごしてしまうような、数多くの特徴をデザインしたのです。平面図を見れば、特定の眺望を強調し、抑揚のある、思いもよらない空間を生み出すために、注意深く構成された幾何学が示されていますが、図面には、空間内での身体の動きを通して、私たちが感じるものは表現されてはいません。ここには、図面には描かれることのない日常のダンスがあって、それは個人的なものですよね。ここでの空間とは、人それぞれ違った動きや関わり方をします。それが心地よいのでしょう。

まだ、建築家が現場で判断していた時代で、それは、人やスケール、そしてタイミングを熟知することで初めて可能になるのです。

工事を行うことは、ただ指示をしたり、規則を守るだけではなく、携わる者同士が理解しあうことでもあったのです。現在では、人々の環境づくりにおける建築家の役割は、以前と比べると二次的なものに過ぎず、私たちはもはや分業化された業務におけるスペシャリストです。指示は驚くほど細かくなり、技術の発展は、超-快適な環境の形成を後押ししてくれるのです。それは、密閉し保護されることでコントロールされた空間によって作られるものなのですが。機械式換気システム、遠隔温度管理、デジタル接続。どういうわけか、私たちは本来の心地よさというものを忘れ、順応性、あるいは順応主義へと移行してしまったのでしょうか?

この建物においては、動線のシステム自体がメインの空間のように思えるのですが。つまり階段が非常によく考えられていますよね。

オルジアティが行った既存の建物への主な操作は、南側ファサードの設計と、垂直の動線計画です。階段は、ある階から別の階への通路である以上に、幾何学的な身体の連なりを生み出す彫刻的なオブジェなのです。そのデザインは、素材と形態の魅力的な並置を特徴としており、連続的に膨らむウールの床は、曲線の幾何学によって強調された真っ白な壁と対照的です。この階段は、曲がりくねった一つの流れであり、人工光源によって遮られる垂直面に沿って、湾曲した形状を作り出しているのです。曲線とは対照的なシャープな直線が、その先にあるアパートの入口へと私たちを誘っています。とても複雑な空間で、広さと狭さ、明るさと暗さ、そして高さと低さの間の張り詰めた空間を体験することになります。

ルドルフ・オルジアティは、地元の骨董品や建物の部品、古い窓、ドア、梁、あらゆる種類の家具の収集家であり、それは、ETHで美術史を専攻した彼の出自と関係しているのかもしれません。おそらく、すべてを元あった場所へと還そうとする試みとして、これらの収集されたものたちをプロジェクトで使用することもありました。

グラウビュンデンという地域には、触覚的で映画的な感覚が感じられます。古い家々が立ち並ぶ谷間には、その土地や、そこに住む人々、そして、そこに建つ建物の間で共有された家具やものが、今でも大事に保管され、使われ続けています。古い洋服ダンス、肘掛け椅子、汚れを落として塗装した古いドアなど、オルジアティはこの家の中で、伝統的なクラフトマンシップを称えるため、そして私たちがこの古い家の中にいることを気付かせてくれる要素として、共同で使用する古い家具をいくつか配置しています。

そうすることで、通りからアパートまでの道のりは長くなりますね。心に残る経験があれば、それは知覚的に、時間を長くするものになります。

その通りです。この階段があれば、アパートまでの道のりがより複雑になり、帰り道はより親しみ深いものになります。新たな動線システムは、建築的にデザインされた中間領域で、アパートを南北軸で分割することで、左右に段差を生み、それにより北側が高くなるので、自然と通りと部屋との間に距離感が生まれます。

オルジアティにとっての官能性とは、感傷や感情といったことに限られたものではなく、ラテン語における「sentire」、つまり気づき、知覚することを意味していました。建物の中から外へと進んでいくときに、手すりの位置が左右で切り替わる決定的な瞬間があるのですが、こうした些細なディテールが、あなたがまさに今パブリックスペースへ足を踏み入れていることをそれとなく気づかせてくれるのです。ハウス・チャラーにおいては、そこでの人の所作を考え抜くことによって、その官能性が獲得されているのだと思います。それがたとえどんな小さなプロジェクトであったとしても、最小限の手法で、記憶に残るような私たちと空間との相互作用をもたらし、そして、美しくも実直な心地よさを私たちに与えてくれたことを思い出させてくれるのです。

2022年10月20日

Giacomo Ortalli: We live in a time of constant movement and exploration. How many of us maintain strong connections to our roots? From a young age we travel, we expand our horizons, we experience new places and cultures: working, touring, studying, it’s possible to quickly arrive at a broad understanding of Europe, and for that matter the wider world, which are obviously very good things; however, there are also consequences; when you move from place to place, it’s easy to lose sight of where you are from and what your actual sense of things is. Perhaps this is true of my own path, nervertheless I am aware of this tension and often return to the words of Mario Merz - “Igloo di Giap” used to describe the perils one faces in battle: “If the enemy masses his forces, he loses ground; if he scatters, he loses strength”.

TODAY, IT’S NOT UNUSUAL FOR AN ARCHITECT TO WORK AND THINK IN NUMEROUS CONTEXTS. TO SOME EXTENT, THE MORE THE MERRIER. WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THIS – IS IT THE ONLY WAY?

More the opposite. Rather than expanding their portfolios of work, some architects opt to remain in a single region and create an architectural vision that is deeply rooted in the local cultural landscape. We are fascinated by these cases.

At the end of his life, Dimitris Pikionis (1887-1968) had the opportunity to intervene in the landscape of Attica, the background and obsession of all his work; he crafted the landscaping works for the archaeological site around the Acropolis in Athens with only local sourced materials and labour. No plans needed - just surveillance and the help of some skilled hands. In another region of the Mediterranean, Alberto Ponis (1933) moved to Palau, Sardegna, and dedicated himself to learning about a given place, thoroughly submerged in a context, a desk full of work, he designed hundreds of houses and realised some unique buildings. In a similar way Geoffrey Bawa (1919-2003) captured the essence of Sri Lanka through its contemporary sensibility.

Much the same, Rudolf Olgiati (1910-1995) was born in Chur, lived and worked in Graubünden his entire life. In the Swiss Alps his work finds its roots. Olgiati mainly built family houses and restored old farmsteads, often working alone, he remained an outsider, even locally he was considered unapproachable. Although his signature was evident, he did not cultivate a style, did not represent a school and did not feel committed to any organisation. This defiladed position gave him the time and the necessary quietness to focus on a strong architectural vision, unperturbed by popular taste. Although Olgiati remained unconcerned with larger arguments or movements, over the years, his studio in Flims did serve as laboratory of thinking and learning for several young architects from the architecture department of the ETH Zurich. Since his death, interest in his buildings has grown, probably to a level greater than during his own lifetime, and his work continues to have lasting influence on the recent generations of Swiss architects.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE HIS WORK?

His built work combines, with great ability, the vernacular traditions of a region and the ethos of a progressive modernism, whilst, above all remaining beautifully sensitive to the alpine landscape. As Peter Märkli noted, he had a rigorous approach to designing small houses as specific nests, formed by constituent elements that cannot be altered and articulated by subtle qualities and details. His houses are independent volumes, often placed in sloping ground, formed by massive white envelopes creating contrasting features, chamfered windows, large openings with specific orientations, sloping mono-pitched stone roofs, tower-like chimneys, arched doors, oversized columns, niches, places full of light, dark corners, all in balance, aspiring to wholeness – a complete work. It is deeply personal work; Olgiati built houses and rooms that he found meaningful and beautiful.

From the interior, rooms are free of symmetrical relationships, shaped to perform for a specific activity; he was not burdened by the modern dogma of „flexible spaces”, that we seem to exclusively contemplate today. On one hand, his work reminded me of Christoph Alexander’s book “A Pattern Language” which elaborates on spatial archetypes, that stem from how people live. Rudolf Olgiati strove to provide responses to common habits and searched for a relationship between architecture and its inhabitants. At the same time, this rootedness to the cultural landscape was subverted by a fascination with ancient Greek architecture and the late sculptural works of Le Corbusier. This conflict creates a kind of tension or even mysticism in his architecture, which is difficult to explain.

His buildings emanate a strong, seemingly independent power. The houses are designed from inside out, from the perspective of the inhabitant as he or she uses each room; the outer form is a consequence. In a way he was quite indifferent to the issue of form and style.

The windows do not respond to exterior geometrical references or axis alignments. You can notice the freedom of placing a large opening on the corner and a small one in the centre within a thick wall and the research of stark contrasts and “chiaroscuro” between shadow and light, a theme which is prevalent in the reveals of Engadin’s massive farmhouses. In this sense we can see an artistic approach in working with volumes with the underlying intention of balancing elements in a unified whole, as a fine sculptor. He was someone who understood presence in form, and the gradations of it.

HOW DID YOU COME TO KNOW HAUS ZSCHALER?

Before founding our own practice, we lived in Chur, working for 8 years at Atelier Peter Zumthor. Haus Zschaler is a prominent residential and commercial building in Chur’s old town, on its north side, an eye-catching 19th century decorated façade, facing Obere Gasse, beautifully restored by the artist Steivan Liun Könz, makes it immediately recognisable. The house was renovated by Rudolf Olgiati in the second half of the 1970’s. He changed the overall circulation, the south side of the building and most of the interiors. On the ground floor, there is a small shop set within a glazed corner and the entrance to a very popular café with a small garden on the south side. Originally, the building contained full-storey flats, Olgiati divided these into eleven small studio flats.

We lived in the loft, under the roof, which in alpine regions, is traditionally dedicated to storage. From the interior, the roof is always an element of memory, with the raw wooden beams in contrast to the smooth white walls. From the window facing northward onto the street below - which on the gable roof is significantly larger than the others - we had a nice view out to the historical townscape. To enter our flat, I had to bow my head because of the low door height. The main room had a sloped double-pitched ceiling with an exceptionally high ridge.

It was like being under a tent with niches and alcoves all around, such as one for sleeping, one for writing, and a small perch for cooking. Everything in that apartment is small, but the spatial richness is beyond any proportion.

Graubünden is a very vital architectural region, and the tradition of craftsmanship is continued in the service of architecture. To this day it remains a holiday destination and there are some benefits to this. Isolation permits an escapism, a lack of perhaps more rigorous questioning, things can be more innocent in a sense, ridded of a learned urbanity, things are freer to be joyful and beautiful on a smaller scale. For instance, a certain pragmatism permitted the southwest façade of Haus Zschaler to be completely cut away and remodeled with angular balconies treated as sculptural elements that cut out the roof like the knuckles of a fist. This radically modern addition is in stark contrast to the historic old town north façade, that remains ornately painted in red, thus preserving the spirit of the historical house and keeping the building in the overall impression of the old town.

We lived there for over 5 years, and it is by far more impressive to experience it spatially than to see it in pictures. To understand Rudolf Olgiati’s building with the senses, one needs to have the real experience of the space. As for many families, with the arrival of our child, the space available in the house reduced, but our apartment allowed a further subdivision, and we all found our place. It was intriguing to witness how we could successfully coexist as 3 in a flat originally designed for two, or less. I think it is interesting, as an architect, to design a space that can be open to diverse uses. Despite the small size, there was a pleasant feeling of living. We lived in that experiment happily.

WHAT DO YOU THINK YOUR SON WILL REMEMBER?

We should ask him! Bachelard wrote that beyond the memory, the native house is physically inscribed in us. I also have this memory connected with the house I lived in as a child. The apartment in Haus Zschaler is also a world, it builds a very human view of the world. As a child, you want to be always in contact with your family, in some way or another. It is an emotional experience, not an intellectual one. The small apartment is made by one big space, high above the street, with views out to the mountains all around and the soft grey carpet on the floor. The more domestic spaces, such as the kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, are reduced to the minimum in favour of the “spazio grande”. The feeling is one of being in a nest, in the best sense of the word.

I believe that the concept of a house which can ‘shield and provide solace’ might originate from the Alps, where hardships are more prevalent than joys derived from outside surroundings. That is why Rudolf Olgiati’s houses are extremely specific to human-oriented bodily senses. In the alpine landscape houses are nests that protect from the outside world, from the severity of the weather and atmospheric phenomena, but also from worldliness and superfluity.

In that same period, we had the occasion to experience other houses, which are somehow the opposite from the apartment we lived in, like Peter Zumthor’s house and atelier where we worked in Haldenstein, as well as Christian Kerez’s Forsterstrasse in Zürich, that we had the opportunity to visit. These houses are conceived with very different principles and provoke strong emotional reactions, at least for us. We are interested in an architecture that is capable of building a world, with its own rules and contradictions. We appreciate architects who develop a personal artistic vision and have a taste which is consistent and stable in time, not altered by temporary fashion.

IN THE FLOOR PLAN OF YOUR APARTMENT THERE IS A SINGLE COLUMN STANDING IN THE MAIN SPACE. WHAT IS THIS COLUMN FOR?

Yes, a massive, concrete column that strikingly sets the scene, the texture of the formwork emphasising the vertical lines and the overall shape slightly tapering towards the top. Olgiati understood the value of not-only-structural columns from Greek classical architecture. As in many of his buildings, large columns were used as focal points to emphasise a specific space. In this specific apartment, such an impressive column situated in the main living space defines the threshold between public and private. Like in the Radulff house in Flims, where the structural part, which is smaller than the column, is pushed back just enough to determine a thin area of shade. This gives the houses a certain monumentality, in relation to the small scale and the domestic program.

IT’S INTERESTING WHY THERE IS ONLY ONE COLUMN OF THIS KIND IN THE ENTIRE BUILDING.

This column is not even present in the plans. Instead, on the ground floor, the garden of the café on the south side is accessible through a large, arched opening marked by two thick columns. Architecture is about what you see, not what you know. The architect designed numerous features in this building of which we remain unaware of. If you to look at the plan, it reveals a carefully composed geometry which is intended to enhance specific views and generate unexpected interior spaces with a continuous tension, but the drawings do not express, what we would feel through the movement in space. Here, there is an undrawn dance to life that is individual, you move and interact differently in these spaces, and it feels good.

It was still during the time when an architect made decisions on site. This is something that occurs when you develop a familiarity with people, scales, and timing.

The construction was not only about instructions and regulations, but an understanding between individuals. Nowadays the role of the architect in building people’s environment is secondary, compared to the past, we are now specialists. Instructions are overwhelmingly elaborated, technological development pushes for hyper-comfort that is achieved with enclosed, protected, and controlled spaces. Mechanical ventilation systems, remote temperature control, digital connectivity. Somehow, we have moved from comfort to conformity, or even conformism?

IT SEEMS THAT THE MAIN SPACE OF THE BUILDING IS THE CIRCULATION SYSTEM - THE VERY ARTICULATED STAIRCASE.