ニコラ・ナヴォーネ: 1969年から1980年代の初頭まで、私の父ミロ・ナヴォーネはヴィガネッロの建築家フランコ・ポンティの事務所でパートナーを務めていました。私が子供の頃は、彼らのスタジオで午後はいつも過ごしていましたし、思春期には彼らが設計し建てた家に住んでいました。

今日、カーサ・グラフについてお話することにしたのは、それがフランコ・ポンティが1950年代にカズラノのサン・ミケーレ村で始めた探求の成果であり、彼の建築の典型のようなものだからです。私がいつも感銘を受けるのは、その内部空間の豊かさと同時に、そのレイアウトのシンプルさなのです。それは少しの言葉で記述されたり、少しの記号に凝縮され得るものなのです。小さくても非常に寛大なこの建物の中には、これらの全てがあるのです。それは私に家庭的空間の考え方を伝えてくれましたし、私が建築を学ぶきっかけとなった重要な役割を果たしていたと思います。

お父様とフランコ・ポンティとの出会いや、お二人のコラボレーションについて教えていただけますか?

私の父は、1955年にティタ・カルローニの事務所で職を得ました。若い建築家たち(その中には私の父や、とても若いころのマリオ・ボッタがいました)には、ストーブに火をつけ、いつも椅子(カルローニのデザインでした)を三つひっつけて眠っているフランコ・ポンティを起こすという仕事があったんだよ、と父は回想していました。

彼は、ちょっとしたボヘミアンみたいなもので、よくナイトクラブに行き、そこで楽しい時間を過ごすだけでなく、クライアントとも知り合いになっていたのです。実際、彼はいつも一文無しでしたが、夜の生活のせい、というわけではなく、本当に寛大な人でしたから。ティタ・カルローニが彼をよく泊めていたこともあり、私の父とポンティはこうして知り合いになったのです。

ただ、彼らの本格的なコラボレーションは、父がトリノのレオナルド・モッソのスタジオで過ごした後の1969年以降に始まったことでした。

二人がともに仕事をしていた頃は、私の父は設計と現場監督、そしてワークフローの整理をしていました。それは、ポンティの時折起こす予測不能な行動がもたらす面倒な影響を避けるためなのですが。いや、フランコの性格が仕事上の過失を意味するものではないことは強調しておくべきですね。逆に、彼は仕事に対してとても厳格で情熱的でしたが、気分や好奇心の赴くままに行動したり、慣習に縛られることがありませんでした。そんな影響もあってか、家の設計に費やす時間をいつも引き伸ばしがちで、その後、作業に戻ってきてはさらに手を加えることが多かったようです。

この頃のティチーノは面白い時代でしたよね。

50年代に入ると、リノ・タミから始まり、その後の若い世代、例えばティタ・カルローニなどの多くのティチーノの建築家たちは、有機主義と呼ばれるものに特別な関心を寄せていました。しかし、彼らはティチーノの田舎の家々、特にアルプス地方にあるものにも魅力を感じていました。その基本的な幾何学の卓越した力強さ、見事な石積みの遂行、そして、これらのアルカイックな結晶体を風景の中に配置する際の極めて高い精度が、そこにあったからですね。一方で、彼らの野心は現代的な空間の質を追求することであり、またそれらの建物と環境とを調和させる方法をも模索していました。つまり、フランク・ロイド・ライトの建築は重要な参照系であったわけです。

ティチーノ州において、そのライト - モデルは二つの方面からもたらされたのです。イタリアからは、亜高山帯の州で多大な影響力と名声を博する批評家、そしてその広報者としてのブルーノ・ゼヴィの仕事を通して。チューリッヒからは、例えば、ヴェルナー・モーザーのモノグラフを通して。

モーザーは、タリアセンで働いた経験があり、1952年の巡回展「Sixty years of Living Architecture: the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright」のスイス展の際に、このモノグラフを出版して成功したわけですが。

ライト - モデルは現代的である一方、地理的のみならず、歴史的そして文化的な理解を踏まえながら、建物に根を与えて、しっかりとその特定の地域に建築を根付かせることを可能にしたのです。驚くべきことに、ティチーノの建築家たちは、それぞれ独自の方法でライトの作品を解釈しているのです。フランコ・ポンティの作品はライト - モデルに最もよく似ているものの一つかと思いますが、類似性という観点からだけ見ていても、表面的な理解にしかなりません。ポンティの作品は、模倣ではなく、独自の再解釈なのです。その最大の特徴は、形と空間に関する、個人的で厳格な文法への探求にあるのだと感じます。そこでの考えは、ポンティが彼のキャリアの初期に共に仕事をし、大きな影響を受けたティチーノ建築(ティチーノ建築以外でもそうですが)の巨匠、ペッポ・ブリビオから借りてきたものです。

この探求はとても困難なもので、というのも、それがポンティが戸建て住宅のみに焦点を当てた理由の一つでもあると思うのです。探求の対象を限定することで、建築の基本的なテーマに的を絞ることができ、理想へと近づくことができたのです。

ポンティの探求は極めて独自なものでしたし、個人的であり、自律的な、ましてやミステリアスなオブジェクトを生み出すことを目的としています。都市の建築を構築する必要性が強調されていた他の重要な運動に対して、ポンティの立場はどのように共存してたのでしょうか?

この時期のティチーノの建築家たちは、実に多様なアプローチをとっていました。ポンティは「反 - 都市」というラディカルな立場をとっていましたが、例えばこれはルイジ・スノッツィとは根本的に異なりますよね。スノッツィは1932年生まれです。(つまり、ポンティより11歳年下ですね)

彼は、彼の活動の最初期に有機主義 - モデルを見ていましたが、やがてティチーノ州の現実 - それは本質的に農村地域であるということ - をそのまま受け入れた建築に不満を持つようになり、広い意味での都市空間の構築に関心を向け、その関心を未だ都市的テーマが未明瞭な場所へと持ち込んでいったのです。ポンティは一方、こういった作業にはあまり関心がありませんでした。彼は、まるで「アルプスのアルカディア」というアイデアに導かれるようにして仕事に取組み、地方や農村の建築の伝統との対話を続けようとしたのです。

実際、ポンティは個人主義者でしたし、集団ではなく個人を信じていました。ポンティの関心の中心にあったのは、常に特定の個人であり、またその人の個性やニーズなのだったのです。同時に、創造的な独自性を重視し、それを実現する方法を模索していました。ですから、彼はライトの非常に有効なメタファー、住宅はクライアントの肖像である、をよく拝借していたのです。肖像画は、描かれた対象の魂を掴んでいくようなものですが、画家は常にそれを自分のやり方で描きますし、建築家は設計することで同じことを志しているのです。

しかし、ポンティの建築的文法は、それ自体が目的化した不合理な妄想ではないのです。

カズラノのサン・ミケーレ村をみてください。これは、文化的建設請負人、エリジオ・ボニが発案した先見性のある事業なのです。彼は、タミやカメンツィントと同世代の優れた建築家、アウグスト・ヤッグリに湖畔の区画整理の計画を依頼しました。ヤッグリは懸命にも、妥当な案、つまりその土地からは最大の利益を得ることのできる案を提案したのです。それから間も無く、ボニはポンティにたった6軒の住宅(最終的には8軒となったのですが。)を委託し、土地の大半に家を建てるというアイデアを一時的に断念することとしたのです。ボニと共にポンティが目指したのは、強い個性を持ちながらも、共通のボキャブラリーを持ち、お互いに対話を生み出すようなアンサンブルだったのです。

ポンティの建築は、同時代の人々にどのように受け入れられたのでしょうか?

ポンティの探求は、実に個人的なものであったので、ティチーノ界隈では常に評価されてはいましたが、例外として見られていて、おそらく刺激的なものであったとは思うのですが、孤立していたのでしょう。彼のキャリアは、若い建築家たちが有機主義 - モデルから離れようとして、ル・コルビュジエのような他の情報源に目を向けていた頃だったのです。有機的建築と合理的建築の風刺的な二分法をここで思い出したいわけではありません。なぜなら、そこには、逆にこれら二つの立場の充実した対話があったからです。ティタ・カルローニの作品のように。いずれにせよ、このことがポンティの作品が過小評価される原因となっているのかもしれません。彼は常に優れた建築家であり、非凡な職人であると考えられてはいましたが、彼の仲間たちに特別な影響を与えるようなことはありませんでした。

彼の手法における基本要素とは何なのでしょうか?

ポンティの作品において「タイプ」という概念が重要な役割を果たしていると思います。はて、「タイプ」という概念ほど「個性」と関係のないものはないのではないか?と思われるかもしれませんね。しかし実はこのコンセプトは、ジャン・カステックスが「Le printemps de la Prairie House」(1986年)で鋭く指摘しているように、ライトの建築の中核でもあるのです。

ポンティは、経験を積むにつれて結晶化させた、一連の基礎的構想からスタートし、限られたルールに基づく厳格な文法と明瞭な幾何学性を用いて、設計概要や敷地の特徴などの制約にぴったりと適した解決策を見つけることができたのです。ポンティは、どういった場合においても、完全に新しいものを生み出すということには興味がありませんでした。

形式的な文法の一貫性、そして先に述べたように、ほぼ戸建て住宅というテーマだけを扱うという決断が、ポンティの作品を分類学的に分別することを可能にしているのです。それぞれの建物は他の建物との共通点、あるいは相違点によってその価値を得るというわけです。これは(建築家にとっては歓迎すべき帰結ではないのですが)その住宅が一目で認識され得る、独特の「スタイル」(最もラディカルなモダニストたちが忌避する批判的なカテゴリーではありますが、一定の有用性もなくはないでしょう)を表明していることを意味するのです。

なぜ直交幾何学がそんなにも重要なのだと思われますか?

幾何学は、擬態することに甘んじることなく、景観に配慮した近代建築をデザインする方法です。ポンティの作品にはヴァナキュラーの模倣はなく、再解釈があるのです。それは全く異なることですね。彼の住宅は遠くから見ても目立つことはありません。近づくことで初めて、幾何学的な形状がゆっくりとその存在を明らかにしていくのです。このことは、この時代のティチーノの多くの建築家にとって共通の関心事でした。まず、ティタ・カルローニの「カーサ・バルメッリ」を取り上げてみましょう。ここでの幾何学は、傾斜地という特殊な場所の形と密接に関係しています。遠くからこの住宅を見分けることはとても難しいのです。過激な幾何学的秩序のために、周辺環境から突出して見えるはずだと思われるかもしれません。しかし、その逆なのです。建物の素材(主には木と石)によって、近づいて初めてその存在がはっきりと現れてくるのです。擬態するような方法ではなく、形式的に独立しており、言葉的にも明快であるにもかかわらず、至近距離で初めて存在感を示し、遠くからは周囲の環境との繊細な対話がなされているという点が面白いと思うのです。これは私たちが多くを学ぶことができる深く貴重な教訓です。このようにして、この地域には、まわりよりも大声で叫び、自らの貧しさを隠蔽するような建築ではなく、対話に励む建築が集まってくることになるのです。

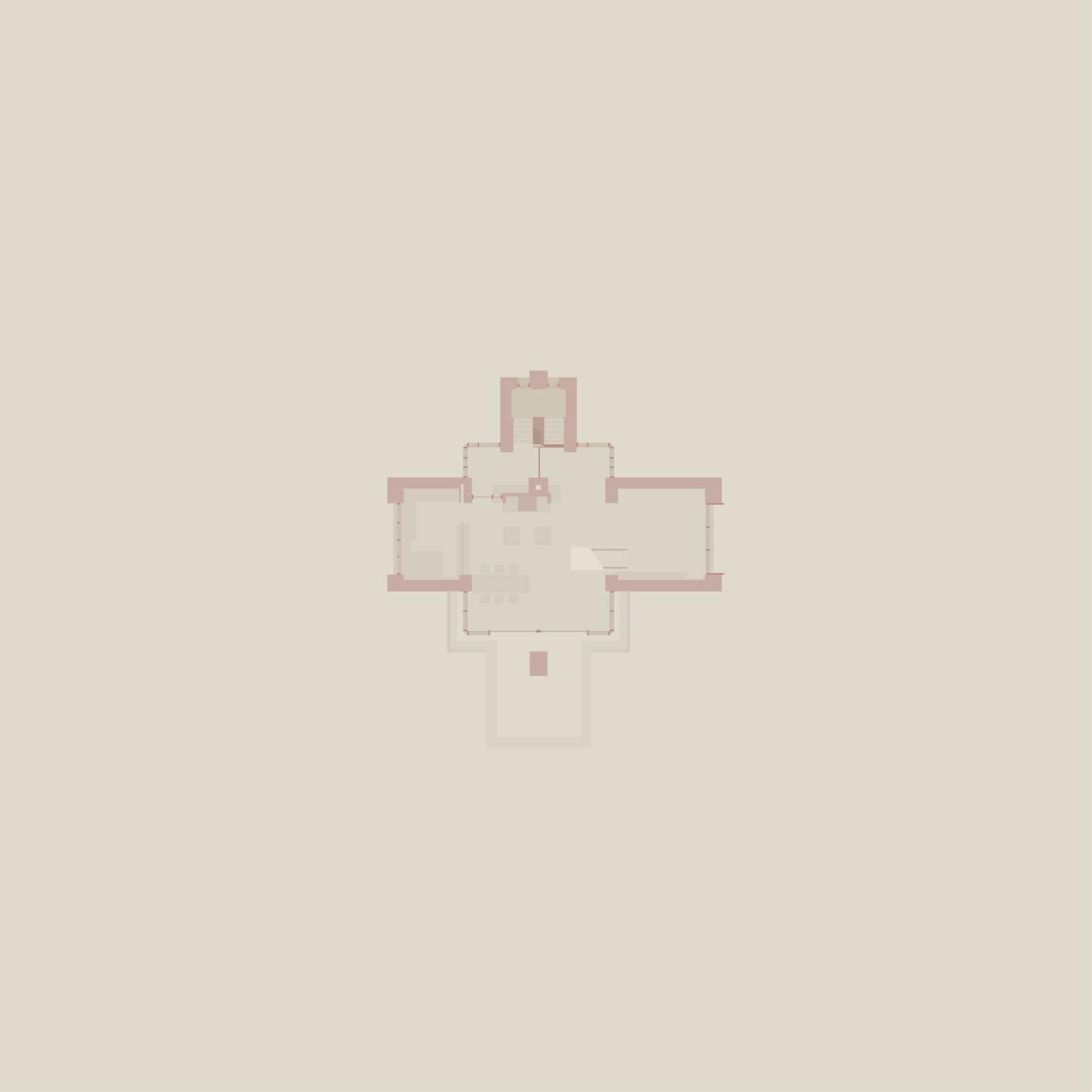

フランコ・ポンティの家のシンプルさと豊かさには目を見張るものがありますね。カーサ・グラフは、例えば、石でできたボリュームの上に屋根が乗っかっているところなど、原始的なアルプスの小屋のプリミティブな特徴を体現していますね。

私もそう思います。でもあなたの説明と全く同じに、というわけではないので注意が必要ですよ。私がこの家を選んだのは、大きな違いを生成するような非常に精密な建築的判断があったからです。あなたは「石でできたボリュームの上に屋根が乗っかっている」とおっしゃったのですが、厳密にはそうではないのです。部屋を内包するボリュームを定義づける急勾配の屋根面は、基礎の花崗岩の石積みと重なり合って、連結したボリュームのイメージを生成しています。つまり、これが、ボリュームの分節的接続から住宅の最も細部のディテールのデザインに至るまで繰り返されるポンティの建築的ディスコースの真の姿なのです。

ここでは、正確な形式的帰結を得るために、全体的な構造計画が行われていることがわかります。ポンティは建設に関する豊富な知識を持ってたので、驚くべき解決策を開発することができたのです。それは注意深くデザインされたディテールに現れています。

この家のもう一つの重要な特徴である暖炉に注目してください。その暖炉のボリュームは中心の軸からわずかにずれて配置されていますね。この暖炉という装置によってエントランスの中庭が定義され、対抗する二つのコーナーウィンドウの間に、思いのほか強力な視覚的対角線が発生し、それらによってダイニングルームの空間と庭とが繋がれるのです。これが、モダンな性格を持った空間であることは明らかで、ヴァナキュラー - モデルとは何ら関係のないものなのです。

本質的なところまで削ぎ落とされながらも、貧相で取るに足らないようなものではなく、非常に限られた手段でもって極限的な空間の質に達するために考えられた、非常にシンプルなジェスチャーというものが、どれほど力強いものとなるのかには驚きますね。

ファサードと勾配屋根から煙突が突き出ている部分をよく見てください。下の部分が太くなっていますね。要素が上へ向かって先細りになっていくという考えを強調しているのですが、文字通り、煙突が地面から伸びて土地に根付いていくかのように、家をその場所に定着させる杭となり、その中心を象徴的に示しているのです。ところが、断面図をよく見ると、これが形式的なトリックであることに気付きます。屋根の上には、二つの鉄筋コンクリートの支持材があって石を支えているのです。これは、ポンティの建築においてはしばしば、プロジェクトに別次元での複雑さを加えるような、視覚的快楽や記号的特徴の探求によって決断がなされることがあることを示していますね。

ポンティの近代的な文法を構成するもう一つの要素は、ペッポ・ブリビオ(彼は新造形主義の建築からそのアイデアを借りてきています)から受け継いだ、壁を穿たないという原則なのです。例えば、ティタ・カルローニは、この原則を気にすることはありませんでしたが。ヴァナキュラー建築では、壁は常に開口部によって穿たれていますし、この種の原則は存在しないのです。しかしフランコ・ポンティの建築においては、開口部とは常に、明瞭に認識可能な要素間に残された空間のことであり、それが壁、床、あるいは屋根であれ、その配置によって、外部との正確な関係を決定しているのです。ポンティは、自身の建築の統語的一貫性に常に細心の注意を払っていました。

地面から生えてきたような重厚な石の塊と、その上に乗っかる軽快な木の構造物という二項対立はポンティの多くの建物に共通しています。このような形式的戦略の目的とは何だったのでしょうか?

そこには、地面に埋め込まれた(あるいは、ライトがよく言っていたように、敷地から生えてきた)塊がしっかりと屹立している、という考え方と、何かがぶさ下がったり、離れたりしているような軽さ、という考え方がありますよね。それはサン・ミケーレ村の家々を見れば明らかなことです。

ポンティはコントラストの探求をしていたのです。モルタルが隠蔽された非常に質の高い花崗岩の壁は、空積みの石壁を模していて、重量感を高めています。ところが、大工工事では対照的に、非物質的な印象を与えるためにも、断面積を減らして薄い金属を使ったりさえしていたのです。現場で撮影された写真に、重い石の塊の上に、蝶の羽のような屋根が繊細に乗っている美しいものがあります。石の塊は人工の地形であり、軽やかな構造物が着地する変形された地形なのですよね。この人工の地形の美しさと、それを取り囲む白樺には、胸を打つものがあります。オーギュスト・ペレの有名な言葉をも思い出させます。「建築とは美しい廃墟を作るものだ」と。ポンティの建築において、永久的なものは、すべて美しい廃墟的状態を目指しているように見えるのです。将来、住宅が寿命を迎えた時には、人工化された風景が現れて、地形としての概念に戻るように緻密に設計されているのです。人間の生活空間を規定するものは一時的なものであり、非常に緻密に建てられたものであっても、いつかは消えてしまうことへの責任を負っている。こういったコントラストはとても詩的なものだと思います。

ある意味、個人主義者になるための最もラディカルな方法は、慣例的な形式とは、形式的関連性を持たず、むしろもっと住まい手に最大の自由が与えられるような抽象的構造や構成の家に住むことだと思うのですが、家という空間がもつ本質的な「家庭性」についてはどうお考えですか?

私は特殊な環境で育ちましたし、その環境が家庭的空間に対する私の基本的な理解を決定的に形成しています。私の感覚では、家を意味論的に認識できるかどうかは問題ではありません。というのも、素晴らしく家庭的である空間の多くが、外観からは家にさえ見えないのです。

カーサ・グラフは、屋根の形からすぐに家だと認識できるのですが、ポンティの全ての住宅がそうだというわけではありません。例えば、私の両親の家はもっと抽象的ですし、家庭性とは、家というものから連想されるイメージに回帰することではないのです。私が面白いと思うのはポンティの家には様々な空間があることです。それらは、全てがフィルタリングされた景色の広がるオープンプランであることが多いのですが、正確で繊細な変化によって空間が結びつけられています。そのおかげで全体の空間の質が増幅しているのです。例えば、床から天井の高さの予期せぬ変化。それに何よりも室内への自然光の入り方。これらの特徴は、住宅の寸法に対する我々の認識を広げてくれるものです。ポンティの建物はどれも外観から想像するよりも、ずっと大きく見えるのです。このことはとても面白い特質だと思うのです。空間のそれぞれの部分が、ただ純粋に機能的なものとしてではなく、明確な行為へのニーズや、その瞬間や、景色に合わせて仕立てられているからです。それぞれの空間は、風景、開口部の種類、照明の度合い、そして他の空間との関係によって独自の性質を持っています。

例えば、カーサ・グラフでは、非常に明るい場所と、陰り、あるいは暗い場所とが絶えず入れ替わっていて、その違いは親密な空間と、風景へと向かう空間との違いのようなのです。私はこの寛容さがとても重要だと思いますし、こういった豊さが必要だと信じています。一つの家の中で、様々な空間体験、雰囲気や光の質の変化を享受できることは素晴らしいことだと思います。

私の育った家には、大きく、そして力強く連結された空間がありました。冬のリビングと夏のリビングのことです。そこにはそれぞれ固定式のソファが置かれていました。前者は暖炉に向かって、後者は風景を見渡すように配置されていたのです。その日の気分や何をするかによって、どちらかの空間を選ぶことができたことを覚えています。二つの空間があることで自由を妨げられていると思ったことはありません。

私はこれらの空間のことを、刻々と変化し続けるメロディーを奏でる楽譜のように考えていました。つまり、楽譜にはルールがありますが、演奏は好きなようにできますよね。それは必ずしも規制を意味するとは限らないということです。なぜなら、こういった空間でも誰もが好きなように自由に生活できるのですから。

カーサ・グラフと、有機的建築以外の建築作品との関連性を示すとしたら、どういったものが考えられるのでしょうか?

ライトへの言及は非常に強く、そのために他の何かと結びつけることは困難ではあるのですが、使用されている素材がティチーノ州の高山地域の建築を参考しているということに加えて、19世紀末のイギリスの居住文化(アーツ・アンド・クラフツ運動のことを考えているのですが。)に言及することはできるでしょう。フランク・ロイド・ライトの建築を育み、ご存知のようにヘルマン・ムテジウムによってドイツ語圏に広められた文化のことです。(アメリカンマスター、ライトがヨーロッパを周遊していた1910年に刊行された彼の偉大な作品集「ヴァスムート・ポートフォリオ」によって、ヨーロッパではライト作品が受容されるわけですが、そのいわば、土台が整えられていたということです)

総じて、ポンティが見ていたものとは、明るさと暗さのある空間が交互に現れたり、守られた感覚と解放された感覚とが調停されているような多様な感覚的体験を特徴とする、こういった家庭的空間の事例なのでしょう。

2021年2月6日

Nicola Navone: From 1969 to the early 1980s my father, Milo Navone, was a partner in the office of the architect Franco Ponti in Viganello. As a child I spent afternoons in their studio and from adolescence I lived in a house they designed and built.

I have chosen to speak about Casa Graf today, because it is the outcome of the research that Franco Ponti began in the 1950s in Villaggio San Michele at Caslano and represents a sort of a paradigm of his architecture. What has always impressed me, is the richness of its internal space and, at the same time, the simplicity of its layout, which can be described in a few words and condensed into a few signs. All this in a building that is small yet extremely generous. It conveys an idea of a domestic space that, I believe, played a crucial role in encouraging me to study architecture.

HOW DID YOUR FATHER MEET FRANCO PONTI AND WHAT IS THE STORY OF THEIR COLLABORATION?

My father got a position in Tita Carloni’s office in 1955. He recalled that every morning young architects (among them my father and a very young Mario Botta) had the duty to turn on the stoves and wake up Franco Ponti, who was usually found sleeping on three chairs (designed by Carloni) tied together.

He was a bit of a Bohemian. He used to go to night clubs where, apart from just having a good time, he also got to know his clients. In fact, he was always broke, not just because of the night life, but he was also very generous. Tita Carloni often put him up, and this is how my father and Ponti got to know each other. Their real collaboration, however, started later, in 1969, after a period spent by my father in Turin in Leonardo Mosso’s studio.

During their years in practice together, my father contributed to the design and supervision of building sites as well as organising the workflow, to avoid the unwelcome effects of Ponti’s sometimes unpredictable conduct. I should stress that Franco’s character did not imply professional negligence. On the contrary, he was very rigorous and passionate about his work, but he followed his moods and curiosity wherever they took him, and he was unrestrained by conventions. One effect of this was that he tended to spin out the time he spent working on his houses, and he would often return to lavish further care on them afterwards.

THOSE WERE INTERESTING TIMES IN TICINO.

From the 50s, many Ticinese architects, starting from Rino Tami and passing to the younger generation, for instance Tita Carloni, expressed a special interest in what was called organicism. But they also shared a fascination with Ticinese rural houses, especially in the Alpine region, for the outstanding force of their elementary geometry, the masterly execution of the magnificent stone masonry, and the extreme precision with which these archaic prisms were placed in the landscape. On the other hand, their ambition was to achieve a modern spatial quality, and they looked for ways to relate their buildings harmoniously to the context. Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture provided a crucial frame of reference.

In Ticino, Wrightian models came from two sides: from Italy, through the work of Bruno Zevi as a critic and publicist who enjoyed great influence and prestige in the subalpine canton, and from Zurich, for instance through the monograph by Werner Moser. He had worked in Taliesin and published that successful volume in 1952 on the occasion of the Swiss leg of the travelling exhibition “Sixty years of Living Architecture: the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright”.

The Wrightian model made it possible to be contemporary while giving buildings roots, embedding them firmly in a particular region, understood not just geographically but also historically and culturally. What is surprising and worth noticing, however, is the originality with which Ticinese architects interpreted FLW’s work, each in their own way. Although Franco Ponti’s oeuvre most closely resembles the Wrightian model, it would be superficial to see it only in terms of similarities. Ponti’s work was an original reinterpretation, not an imitation. I feel its most important feature is the investigation of a personal and rigorous grammar of forms and spaces, an idea which he borrowed from Peppo Brivio, a master of Ticinese architecture (and much else), whom Ponti worked with in the early stages of his career and who had a profound influence on him.

This research was difficult, and I believe this was also one of the reasons why Ponti decided to focus only on single-family houses. Limiting the field of investigation enabled him to focus on fundamental architectural topics and bring them to perfection.

HIS RESEARCH IS EXTREMELY INDIVIDUAL, AIMED AT PRODUCING PERSONAL, AUTONOMOUS, EVEN MYSTERIOUS OBJECTS. HOW DID PONTI’S POSITION COEXIST WITH OTHER IMPORTANT MOVEMENTS STRESSING THE NEED TO BUILD THE ARCHITECTURE OF A CITY?

The architects of this period in Ticino had substantially diverse approaches. Ponti had a radical “anti-urban” position, fundamentally different from Luigi Snozzi’s, for instance. Snozzi was born in 1932 (hence 11 years younger than Ponti).

He looked at the organicist model in the very early stages of his work. Soon, however, he was no longer satisfied with architecture that accepted the reality of Ticino as it had been – essentially a rural region – and began to direct his interests towards the construction of urban space, understood in the broadest sense, bringing urban themes to places where they were not yet articulated. Ponti, by contrast, was not deeply interested in this kind of operation. He worked as if guided by the idea of an “alpine arcadia”, trying to keep up a dialogue with local and rural building traditions.

In fact, Ponti was an individualist, who believed in individuals, not the collective. At the centre of Ponti’s interest was always a specific person, with his or her personality and needs. At the same time, he placed the emphasis on creative independence and sought ways to achieve it. For this reason, he also borrowed from FLW the very efficient metaphor of a house as a portrait of the client. A portrait grasps the soul of the subject painted, but the artist always paints it in his or her own way, and the architect aspires to do the same by designing.

Ponti’s search for an architectural grammar, however, was not an irrational obsession engaged in for its own sake. Consider Villaggio San Michele in Caslano. It was a far-sighted operation originated by the cultivated building contractor Eligio Boni. He asked Augusto Jäggli, an excellent architect from the generation of Tami and Camenzind, to draft a parcelling project for a plot on the lakeside, and Jäggli diligently presented him with a decent proposal, which nevertheless sought to make the most profit from the plot of land. Shortly after this, Boni decided to entrust Ponti with the design of only 6 houses there (in the end they became 8), temporarily giving up the idea of building on most of the land. Ponti’s ambition, shared by Boni, was an ensemble consisting of houses with a strong individual character, yet sharing a common vocabulary that would create a dialogue between them.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE RECEPTION OF HIS ARCHITECTURE BY HIS CONTEMPORARIES?

Ponti’s research was so personal that in the Ticinese panorama his work has always been appreciated, but seen as an exception, perhaps stimulating but isolated. Then his career came at the time when young architects wanted to move away from organic models and were looking at other sources like Le Corbusier. I don’t want to recall here the caricatural dichotomy between organic and rational architecture, since there was – on the contrary – a fruitful dialogue between these two positions, as in the work of Tita Carloni. All the same, this may have contributed to Ponti’s work being underrated. He was always considered a good architect, an extraordinary craftsman, yet without any particular influence on his colleagues.

WHAT WERE THE FUNDAMENTAL COMPONENTS OF HIS METHOD?

I think that in Ponti’s work the concept of the ‘type’ plays an important part. Now, you may ask what can be less related to the idea of “individuality” than the idea of “type”? But, in fact, this concept is also central to Wright’s architecture, as was perceptively shown by Jean Castex in Le printemps de la Prairie House (1986).

Starting from a series of basic schemes, which Ponti crystallised as he gained experience, and using a rigorous grammar based on a limited number of rules and characterised by a clear geometry, he was able to find solutions that were perfectly suited to the constraints of the brief and the features of the site. Ponti was not interested in inventing something completely new in every case.

The coherence of the formal grammar, and, as I have said, the decision to deal almost exclusively with the theme of the single-family house, make it possible to devise a taxonomic classification of his work, in which each building acquires a value by virtue of what it has in common with other buildings in the same series or what distinguishes it from them. This means (as a corollary not unwelcome to an architect) that his houses are immediately recognisable, manifesting a peculiar “style” (a critical category abhorred by the most radical Modernists, but not without a certain usefulness).

WHY WAS ORTHOGONAL GEOMETRY SO IMPORTANT?

Geometry was a way of designing modern architecture that cares for the landscape without indulging in mimesis. There is no imitation of the vernacular in Ponti’s work, there is a reinterpretation, which is quite different. His houses do not stand out from a distance. Only as you get closer does the geometry slowly reveal their presence. This was a common concern for many architects in Ticino in this period. Let’s take Casa Balmelli by Tita Carloni first. Geometry here is closely related to the landforms of a specific place, the sloping terrain. It is very difficult to make out the house from a distance. It might seem that because of its radical geometrical order it ought to be visible, standing out from its setting. The opposite is true. Its presence emerges clearly only when you come closer to it, thanks to its materials (mainly wood and stone). I find it interesting that he was able to make something that is not mimetic, that achieves formal independence and clarity of language, but which only becomes a distinct presence when seen fairly close up, while establishing a delicate dialogue with its surroundings from a distance. This is a profound and precious lesson that we can learn a lot from. In this way the region would end up being populated by buildings engaged in a dialogue, not by architecture that tries to mask its poverty by shouting louder than the others.

THE SIMPLICITY AND RICHNESS OF FRANCO PONTI’S HOUSES IS STRIKING. CASA GRAF MANAGES TO EMBODY THE PRIMITIVE CHARACTER OF PRIMORDIAL ALPINE HUTS: A ROOF RESTING ON VOLUMES MADE OF STONE.

I agree, but we need to be careful, as it is not exactly as you describe it. I chose this house also because of very precise architectural decisions that make a big difference. You said “a roof resting on volumes made of stone”. That’s not precisely true. The steeply sloping planes of the roof that define the volume housing the rooms overlap the granite masonry of the basement, generating the image of interlocked volumes: a true figure of Ponti’s architectural discourse, which recurs from the volumetric articulation to the design of the smallest details of his houses.

We can see that there is a whole constructional research here aimed at reaching a precise formal result. Ponti possessed significant constructional knowledge that enabled him to develop surprising solutions underlined by carefully designed details.

I would like to direct your attention to another important feature of this house: the fireplace, whose volume is set slightly off the central axis. Through this device the atrium of the entrance is defined, and an unexpected and extremely strong visual diagonal is created between two opposite corner windows, capable of linking the space of the dining room with the garden. It is clearly a space with a modern character, having nothing to do with vernacular models.

It is astonishing how strong a very simple gesture can become if one works to reduce it to essentials, not impoverishing or trivialising but striving to achieve an extraordinary spatial quality with very limited means.

Take a closer look at the facade and the point where the chimney projects from the pitched roof. It’s thicker in its lower part. This emphasises the idea of an element tapering towards the top, literally as if the chimney was growing out of the ground and rooting it to the land, becoming a peg anchoring the house to the place and symbolically marking its centre. If you look carefully at the section drawings, you realise that this is a formal trick. There are two consoles of reinforced concrete on the roof supporting the stones. It shows that in Ponti’s architecture there are often decisions driven rather by the search for visual comfort or semiotic features that add another level of complexity to the project.

Another component of Ponti’s modern grammar is the principle, taken from Peppo Brivio (who borrowed it from Neoplastic architecture), of never piercing a wall. Tita Carloni, for instance, never cared about this rule. In vernacular architecture the wall is always pierced by apertures, and no such principle of this kind exists. But in Franco Ponti’s architecture the apertures are always the spaces left between clearly recognisable elements which, by their arrangement, determine a precise relationship with the exterior, whether they are walls, slabs, or roofs. And Ponti is always extremely attentive to the syntactic coherence of his architecture.

THE DICHOTOMY OF A HEAVY STONE BLOCK GROWING OUT OF THE GROUND AND A LIGHT WOODEN STRUCTURE SITTING ON TOP OF IT IS COMMON TO A NUMBER OF PONTI’S BUILDINGS. WHAT WAS THE PURPOSE OF THIS FORMAL STRATEGY?

There is the idea of a mass embedded in the ground (or, as Wright used to say, growing out of the site) and standing firmly in place, and an idea of something hanging, detached, of lightness. This is very evident when we look at the houses in the Villaggio San Michele.

Ponti made a study of contrasts. The granite walls of exceptionally fine quality with concealed mortar to simulate a dry-stone wall heighten the impression of weight. In the carpentry work, by contrast, he sought to convey an impression of dematerialisation, even using metal profiles to reduce the sections. There are beautiful photos from the construction site showing the roofs like the wings of a butterfly resting delicately on the heavy blocks. It is an artificial topography, a modified terrain on which the light structures have landed. The beauty of this artificial topography together with the birches surrounding it, is striking. It also recalls Auguste Perret’s famous dictum, “Architecture is what makes beautiful ruins.” In Ponti’s architecture everything that is permanent seems to aspire to the status of a beautiful ruin. It is designed with such precision and care that in some future time, when the houses come to the end of their lives, it will appear an anthropised landscape and return to the idea of topography. What defines the space of human life could be temporary, built with extreme precision but liable to disappear one day. I find this contrast very poetic.

IN A SENSE, THE MOST RADICAL WAY TO BE AN INDIVIDUALIST WOULD BE TO LIVE IN A HOUSE THAT HAS NO FORMAL LINK TO CONVENTIONAL FORMS AND IS MORE LIKE AN ABSTRACT STRUCTURE OR COMPOSITION, ALLOWING ITS FULL APPROPRIATION BY THE USER. WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE INTRINSIC “DOMESTICITY” OF THE SPACE OF A HOUSE?

I grew up in a specific environment, that definitely formed my basic understanding of a domestic space. To my sensibility, it’s not a problem of the semantic recognisability of a house, because many incredibly domestic spaces don’t even look like houses from outside.

In Casa Graf it is immediately readable, because of the shape of the roof. But not all Ponti’s houses are like that. My parents’ house, for instance, is more abstract. It is not about returning to the imagery that we associate with the idea of a house. What I find interesting is the variety of spaces that we find in Ponti’s houses. They often have open plans where you have a filtered view of everything, yet their space is articulated through precise and subtle changes, that amplify the general spatial quality: unexpected shifts in the floor and ceiling heights, and most of all through the way natural light is brought indoors. These features help expand the perception of the dimensions of a house. Ponti’s buildings all look much larger than you expect them to be judging just from their external presence. And I believe this is a very interesting quality. They feel larger because each portion of space is tailored to the needs of a precise action, moment or view, yet without being purely functional. Each space has its own character created by its relationship with the landscape, the type of aperture, degree of illumination and the way they relate to the other spaces.

Casa Graf, for instance, constantly switches between very bright and shaded or darker areas, just like the difference between intimate spaces and ones projected towards the landscape. I find this generosity very important, and I believe in the necessity of this kind of richness. It’s wonderful that a house can offer an array of different spatial experiences, atmospheres and variable qualities of light.

In the house where I grew up there was a large, strongly articulated space, with a winter and a summer living room, each with a fixed sofa. The former was placed facing the fireplace and the latter looking out over the landscape. I remember that I could choose one of these two spaces depending on my mood or what I meant to do. I never felt that the fact of having these two spaces diminished my freedom. I treated it as a musical score on which I could play an ever-changing melody. A musical score has rules, but I play the music the way I want to. It is not necessarily a constraint; in this kind of space everyone is free to live as they please.

IF YOU HAD TO ESTABLISH A CONNECTION BETWEEN CASA GRAF AND OTHER WORKS OF ARCHITECTURE APART FROM ORGANICISM, WHAT WOULD YOU THINK OF?

The reference to Wright is so strong that it’s hard to connect it with other sources. But, in addition to the reference, in the materials used, to the architecture of the alpine regions of Ticino, we could mention the culture of the English dwelling at the end of the 19th century (I am thinking of the Arts & Crafts movement), which also nurtured Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture and was spread in the German area, as we know, by Hermann Muthesius (preparing the field, so to speak, for the reception of Wright’s work through the magnificent Wasmuth portfolio in 1910, on the occasion of the American master’s European trip). In general, I would say that Ponti looked at those examples of domestic space characterised by a great variety of sensory experiences, alternating bright and shadowy spaces and reconciling a sense of protection and at the same time openness to the landscape.

06.02.2021

尼古拉·纳沃乃: 1969年到八十年代初,我父亲,米罗·纳沃乃(Milo Navone),是在维加内罗(Viganello)的佛朗哥-庞蒂(Franco Ponti)事务所的一名合伙人。孩童时我在他们的工作室度过了一些下午,而从青春期开始,我住在一栋由他们设计和建造的住宅里。

我今天选择谈论格拉夫住宅(Casa Graf),因其是佛朗哥-庞蒂在20世纪50年代开始在卡斯拉诺(Caslano)的圣客米凯莱村(Villaggio San Michele)的研究的结果,代表了他的建筑的某种范式。一直来使我印象深刻的,是其内部空间的丰富,于此同时,布局上的简洁,能够被几个词语所描绘或浓缩为几个标志。所有这一切都在一个小而极其慷慨的建筑中。它传达了一种居家空间的理念,我相信,这种理念在激励我学习建筑方面起到了关键的作用。

你的父亲是怎么认识弗朗克客庞蒂的,他们的合作又有什么样的故事呢?

1955年,我父亲在蒂塔·卡洛尼(Tita Carloni)事务所获得了一个职位。他回忆说,每天早上年轻建筑师(其中有我父亲和年轻的马里奥·博塔(Mario Botta)要负责点燃炉子并叫醒弗朗克客庞蒂,通常会发现他睡在绑在一起的三张椅子上(由卡洛尼设计)。

他有点像个波西米亚人。他经常去夜店,享受了一段快乐时光之外,也认识了一些他的客户。事实上他总是身无分文,不仅因为夜生活,也因为他非常慷慨。蒂塔客卡洛尼经常让

他留宿,这就是我父亲和庞蒂认识的过程。

然而他们真正的合作,开始在之后, 1969年,在我父亲在都灵的莱昂纳多·莫索(Leonardo Mosso)事务所待了一段时间之后。

在他们共同实践的几年里,我父亲对设计、现场监工以及工作流程的组织做出了贡献,以避免庞蒂有时不可预测的行为造成不受欢迎的影响。我要强调一下,佛朗哥的性格并不意味着职业上的疏忽。相反,他对自己的工作非常严谨而热情,但他会追随自己的情绪和好奇心,无论被带向哪里,他都不受传统的约束。这样做的一个结果是,他倾向于把花在住宅上的时间挤出来,而且他经常在事后回来对房子进行进一步的维护。

那曾是提挈诺有趣的时代

从50年代起,许多提挈诺建筑师,从里诺-塔米(Rino Tami)开始,到年轻一代,例如蒂塔-卡洛尼,都对所谓的有机主义表现出特殊的兴趣。然而他们也对提挈诺的乡舍,特别是阿尔卑斯山区的,有着共同的迷恋,因其彰显的卓越力量,那来自原始几何形,来自宏伟的石头砌筑物的巧妙处决,以及来自这些古老的棱角置于景观中的极端精确性。另一方面,他们的志向在于获得现代性的空间质量,他们寻找方法将他们的建筑与环境和谐地联系起来。弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的建筑提供了一个关键性的参考框架。

在提契诺州,赖特的模式来自两方面:一是来自意大利,通过布鲁诺-泽维(Bruno Zevi)的工作,他是一位批评家和宣传家,在阿尔卑斯山州享有巨大的影响力和威望;二是来自苏黎世,例如通过维尔纳-莫泽(Werner Moser)的专著。

他曾在塔利辛(Taliesin)工作过,并在1952年 “活的建筑60年:弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的作品 “巡回展览的瑞士站时期出版了那本成功的书。

赖特的模式使得建筑在具有当代性的同时能够赋予建筑根基,将其牢牢地嵌入到一个特定的区域,不仅在地理上,而且在历史和文化上也能解读。然而,令人惊讶和值得注意的是,提挈诺建筑师以自己的方式诠释了赖特的工作,每个具有其独创性。尽管弗朗哥客庞蒂的作品与赖特的模式最为相似,但如果只从相似性的角度来看,那就太肤浅了。庞蒂的作品是一种原创的重新诠释,而不是模仿。我觉得它最重要的特点是对形式和空间的个人化且严格的语法的研究,这个想法是他从佩波-布里维奥(Peppo Brivio)那里借鉴来的,他是提契诺建筑(和其他很多东西)的大师,庞蒂在他职业生涯的早期阶段和他一起工作,对他有深刻的影响。

这项研究很困难,我相信这也是庞蒂决定只关注单一家庭住宅的原因之一。对研究领域的限制使他能够专注于基本的建筑主题,并使其达到完美的效果。

他的研究是非常个人化的,旨在制造个人的、自主的、甚至是神秘的物体。庞蒂的立场是如何与其他强调建造城市建筑需要的重要运动共存的?

这一时期提契诺州的建筑师们实质上的追求各不相同。例如,庞蒂有一个激进的 “反城市 “立场,与路易吉-斯诺齐(Luigi Snozzi)的立场有根本上的不同。斯诺齐生于1932年(因此比庞蒂年轻11岁)。

在他工作的早期阶段,他研究了有机主义模式。但很快,他就不再满足于接受建筑在提契诺州的现实——这基本上是一个农村——并开始将兴趣转向城市空间的建设,从最广泛的意义上理解,将城市主题带到尚未阐明的地方。相比之下,庞蒂对这种操作并不深感兴趣。他的工作仿佛是在 "阿尔卑斯山世外桃源 (alpine arcadia)"的理念指导下,试图与当地和乡村的建筑传统保持对话。

事实上,庞迪是一个个人主义者,他相信个人而不是集体。庞蒂的兴趣中心始终是一个具体的人,有他或她的个性和需求。同时,他把重点放在有创造力的独立性上,并寻求实现这种独立性的方法。出于这个原因,他还从赖特那里借用了一个非常有效的比喻:住宅是客户的画像。肖像画抓住了被画对象的灵魂,而艺术家总是以自己的方式作画,建筑师也渴望通过设计来做到这一点。

然而,庞蒂对建筑语法的探索并不是出于自身追求的非理性执迷。考虑到卡斯拉诺的圣客米凯莱村,这是由有修养的建筑承包商埃利吉奥-波尼(Eligio Boni)发起的一项有远见的行动。他请奥古斯托-雅格利(Augusto Jäggli),一位来自塔米和卡门辛德(Camenzind)那一代的优秀建筑师,为湖边的一块地的一个分包项目画草图,雅格利辛勤地向他提交了一个得体的方案,但还是想从这块土地上获取最大的利润。此后不久,波尼决定委托庞蒂在那里只设计6栋住宅(最后变成了8栋),暂时放弃了在大部分土地上建造的想法。庞蒂的雄心壮志,与波尼一样,是由具有强烈个性的住宅组成的集合体,但共享一个共同的语汇,这将在它们之间创造对话。

您如何描述同时代人对他的建筑的接受情况?

庞蒂的研究是如此的个人化,以至于在提契诺的全景视野中,他的作品一直获得欣赏,却被视为一个例外,也许令人受到启发,但却是孤立的。他那时的职业生涯正在年轻建筑师想要摆脱有机主义模型,并且正在寻找其他来源,如勒-柯布西耶的时候。我不想在这里回顾有机建筑和理性建筑之间滑稽的二分法,因为恰恰相反,这两种立场之间存在着富有成效的对话,比如在蒂塔-卡洛尼的作品中。尽管如此,这可能导致了庞蒂的作品被低估。他一直被认为是一个优秀的建筑师,非凡的工匠,但对他的同侪们没有任何特别的影响。

他的方式的基本组成部分是什么

我认为,在庞蒂的作品中,"类别 "的概念起着重要的作用。现在,你可能会问,还有什么能比 "类别 "的想法与 "个性 "的想法更不相关呢?但事实上,这个概念也是赖特建筑的核心,正如让-卡斯特克斯(Jean Castex)在《草原之家(Le printemps de la Prairie House)》 (1986)中敏锐地标示的那样。

从一系列的基本策略(scheme)开始,庞蒂随着经验的积累将这些策略具象化,并使用基于有限规则和清晰几何形的严格语法,他得以找到完全适应任务书限制和场地特点的解决方案。对于在每个案例中创造全新的东西,庞蒂不感兴趣。

由于其形式语法的连贯性,以及几乎只处理单一家庭住宅这一主题的设计决策(如我所述),使得我们有为他的作品设计分类法的可能性。在这个分类法中,根据它与同系列其他建筑的共同点或与之的区别点,每座建筑可以获得一定的价值。这意味着(对建筑师来说一个不愉快的必然结果),他的房子是可以被立即识别的,表现出一种独特的 "风格"(被最激进的现代主义者所厌恶的评判类别,但并非没有某种用途)。

为什么正交几何如此重要?

几何学是设计现代建筑的一种方式,它关心景观而不沉溺于模仿。在庞蒂的作品中,没有对乡土的模仿,有的是一种重新诠释,这是有极大区别的。他的房子从远处看并不显眼。只有当你走近时,几何形才会慢慢显示出它们的存在。这也是这一时期提契诺州许多建筑师共同的关注点。我们先来看看蒂塔-卡罗尼的巴尔梅利住宅(Casa Balmelli)。这里的几何学与特定的地貌,即倾斜的地形密切相关。从远处看很难看出这个房子。似乎由于其激进的几何秩序,它应当是显眼的,从环境中脱颖而出。然而事实恰恰相反。只有当你走近它时,它的存在才会清晰地浮现,这要归功于它的材料(主要是木材和石头)。我觉得有趣的是,他能够创造出一些没有模仿的东西,实现形式上的独立和语言上的清晰,但只有在相当近的地方观察时才会成为一个鲜明的存在,同时从远处又与周围的环境建立起微妙的对话。这是一堂深刻而宝贵的课程,我们可以从中学到很多。通过这种方式,聚集于此地的最终会是参与对话的建筑,而不是那些试图通过更大声的呼喊来掩盖其自身贫乏的建筑。

弗朗科-庞蒂住宅的简单和丰富令人震惊。格拉夫住宅成功地体现了原始阿尔卑斯山小屋的特征。屋顶安放在石头的体量上。

我同意,但我们需要小心,因为它并不完全像你描述的那样。我选择这所住宅也是因为非常精确的建筑决定会形成很大的不同。你说:"屋顶放在石头做的体量上"。这并不完全正确。屋顶陡峭的斜面定义了房间的体积,与地下室的花岗岩砖石重叠,产生了体量互锁的图像:这是庞蒂建筑论述的真实写照,从体量的衔接到他房屋的最小细节的设计,都是如此。

我们可以看到,这里有着整体的建造研究,旨在达到一个精确的形式结果。庞蒂拥有重要的建筑知识,使他能够通过精心设计的细节来发展出令人惊讶的解决方案。

我想将你的注意力引向这所住宅的另一个重要节点:壁炉,其体量略微偏离中轴线。通过这个装置,入口处的中庭被定义,在两个相对的角窗之间形成了一个意想不到的、极其强烈的视觉对角线,能够将餐厅的空间与花园联系起来。这显然是一个具有现代特征的空间,与乡土模型毫无关系。

令人惊讶的是,如果人们努力将一个很简单的姿态削减到本质,它可以变得如此强大,不是贫乏或琐碎,而是努力以极为有限的手段实现非凡的空间质量。

仔细看看外墙和烟囱从斜屋顶上伸出来的地方。它的下部比较厚。这强调了一个元素向顶部逐渐变小的想法,从字面上看,就像烟囱从地面上长出来并扎根于土地,成为一个钉子,将房子固定在这个地方,并象征性地标记其中心。如果仔细看一下剖面图,你会意识到这是一种形式上的技巧。屋顶上有两个钢筋混凝土的支柱,支撑着这些石头。这表明,在庞蒂的建筑中,往往有一些决策驱使于寻求视觉舒适性或符号学特征,这些特征为项目增加了另一个层次的复杂性。

庞蒂的现代性语法的另一个组成部分取自佩波-布里维奥(他从新古典主义建筑中借用)的原则,即永远不要刺穿墙壁。例如,蒂塔-卡洛尼就从不关心这一规则。在乡土建筑中,墙壁总是被开孔穿透,不存在这样的原则。但在佛朗哥-庞蒂的建筑中,孔洞总是明晰的元素之间的空隙,这些元素经过排布,确定了建筑与外部的精确关系,不论它们是墙壁、楼板还是屋顶。庞蒂总是非常注意他的建筑的句法一致性。

庞蒂的许多建筑都有这样的特点:沉重的石块从地下长出,而轻盈的木质结构坐落于上,这种二分法很常见。这种形式策略的目的是什么?

在这里,有一种嵌入地面(或如赖特常说的,从场地中生长出来)并牢固地站在原地的想法,也有一种悬挂的、分离的、轻盈的想法。当我们看到圣客米凯莱村的住宅时,这一点就非常明显了。

庞蒂做了一项对比研究。品质卓越的花岗岩墙,用将砂浆遮蔽的方式来模拟干砌墙,增加了重量感。相比之下,在木作中,他试图传达一种非物质化的印象,甚至使用金属型材来减少截面。一些施工现场的美好照片显示,屋顶就像蝴蝶的翅膀一样,精妙地停留在沉重的砖块上。这一轻型结构坐落于一处由自然地形改造而来的人造基础之上。改造后的场所融合进了周围的白桦树林,获得了别样的美感。它也让人想起奥古斯特客佩雷的箴言:“建筑是创造美丽的废墟”。在庞蒂的建筑中,所有永久性的东西似乎都渴望成为美丽的废墟。它被设计得如此精确和谨慎,以至于在未来的某个时候,当房屋的寿命结束时,它将成为一个留有人类痕迹的景观,并回归到纯粹的地形学概念。尽管极端地精心设计与建造,那些定义人类生活空间的东西,依旧是有时效性的,终有一天会消失。我感觉这对比是非常有诗意的。

从某种意义上说,成为个人主义者的最激进的方式是住在一个与传统形式没有联系的住宅里,它更像一个抽象的结构或构图,允许使用者完全占有它。你对住宅空间的内在 "居家性 "怎么看?

我在一个特定的环境中长大,这无疑形成了我对家庭空间的基本理解。在我的感觉中,这不是一个住宅语意的识别性的问题,因为许多令人难以置信的居家空间从外面看甚至都不像住宅。

在格拉夫住宅中居家性是可以立即被读出来的,由于屋顶的形状。但不是所有庞蒂的住宅都是这样的。例如,我父母的住宅,是更抽象的。这并不是要回到我们与住宅的概念相关的意象。我发现有趣的是,我们在庞蒂的住宅里发现了各种各样的空间。它们通常有开放的平面,你可以看到所有的东西,然而这些空间是通过精确和微妙的变化来阐述的,像是放大了普通的空间质量:地板和天花板高度的意外变化,以及最重要的是通过自然光被引入室内的方式。这些特点有助于扩大人们对房屋尺寸的感知。仅仅从外观表现来判断,庞蒂的建筑看起来都比你预期的大得多。而我认为这是一个非常有趣的品质。感觉更大是因为每一部分空间都是根据精确的行动、时刻或景观的需要而定制的,但又不纯粹是功能性的。每个空间都有自己的特点,由其与景观的关系、孔洞的类型、照明的程度以及它们与其他空间的关系所创造。

例如,格拉夫住宅,在非常明亮和阴影或较暗的区域之间不断切换,就像私密的空间和向风景投射的空间之间的区别。我觉得这种慷慨是非常重要的,而且我相信这种丰富性的必要性。一所房子可以提供一系列不同的空间体验、气氛和可变的光线质量,这是绝妙的。

在我长大的房子里,有一个大的、强有力衔接的空间,有一个冬天的和一个夏天的客厅,其中都有一个固定的沙发。前者面对着壁炉,后者望向外面的风景。我记得我可以根据我的心情或我想做的事情,在这两个空间中选择一个。我从来不觉得拥有这两个空间的事实削弱了我的自由。

我把它当作一个乐谱,我可以在上面演奏不断变化的旋律。乐谱有规则,但我以我想要的方式演奏音乐。

这不一定是一种约束;在这种空间里,每个人都可以自由地生活,随心所欲。

如果要你在格拉夫住宅和有机主义以外的其他建筑作品之间建立联系,你会想到什么?

对赖特的参考是如此强烈,以至于很难将其与其他来源联系起来。但是,除了在所使用的材料中提到提契诺州阿尔卑斯山地区的建筑外,我们还可以提到19世纪末的英国住宅文化(我想到的是工艺美术运动),它也培养了弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的建筑,并在德国地区传播,正如我们所知,由赫尔曼-穆特希斯(Hermann Muthesius)(可以说是通过1910年美国大师欧洲之行时,非凡的沃斯默思作品集(Wasmuth portfolio)为接受赖特的作品准备了场合)。总的来说,我想说的是,庞蒂关注的是那些以巨大的感官体验为特征的家庭空间的例子,明亮和阴暗的空间交替出现,调和了保护感和同时对景观的开放。

2021年2月6日

ニコラ・ナヴォーネ: 1969年から1980年代の初頭まで、私の父ミロ・ナヴォーネはヴィガネッロの建築家フランコ・ポンティの事務所でパートナーを務めていました。私が子供の頃は、彼らのスタジオで午後はいつも過ごしていましたし、思春期には彼らが設計し建てた家に住んでいました。

今日、カーサ・グラフについてお話することにしたのは、それがフランコ・ポンティが1950年代にカズラノのサン・ミケーレ村で始めた探求の成果であり、彼の建築の典型のようなものだからです。私がいつも感銘を受けるのは、その内部空間の豊かさと同時に、そのレイアウトのシンプルさなのです。それは少しの言葉で記述されたり、少しの記号に凝縮され得るものなのです。小さくても非常に寛大なこの建物の中には、これらの全てがあるのです。それは私に家庭的空間の考え方を伝えてくれましたし、私が建築を学ぶきっかけとなった重要な役割を果たしていたと思います。

お父様とフランコ・ポンティとの出会いや、お二人のコラボレーションについて教えていただけますか?

私の父は、1955年にティタ・カルローニの事務所で職を得ました。若い建築家たち(その中には私の父や、とても若いころのマリオ・ボッタがいました)には、ストーブに火をつけ、いつも椅子(カルローニのデザインでした)を三つひっつけて眠っているフランコ・ポンティを起こすという仕事があったんだよ、と父は回想していました。

彼は、ちょっとしたボヘミアンみたいなもので、よくナイトクラブに行き、そこで楽しい時間を過ごすだけでなく、クライアントとも知り合いになっていたのです。実際、彼はいつも一文無しでしたが、夜の生活のせい、というわけではなく、本当に寛大な人でしたから。ティタ・カルローニが彼をよく泊めていたこともあり、私の父とポンティはこうして知り合いになったのです。

ただ、彼らの本格的なコラボレーションは、父がトリノのレオナルド・モッソのスタジオで過ごした後の1969年以降に始まったことでした。

二人がともに仕事をしていた頃は、私の父は設計と現場監督、そしてワークフローの整理をしていました。それは、ポンティの時折起こす予測不能な行動がもたらす面倒な影響を避けるためなのですが。いや、フランコの性格が仕事上の過失を意味するものではないことは強調しておくべきですね。逆に、彼は仕事に対してとても厳格で情熱的でしたが、気分や好奇心の赴くままに行動したり、慣習に縛られることがありませんでした。そんな影響もあってか、家の設計に費やす時間をいつも引き伸ばしがちで、その後、作業に戻ってきてはさらに手を加えることが多かったようです。

この頃のティチーノは面白い時代でしたよね。

50年代に入ると、リノ・タミから始まり、その後の若い世代、例えばティタ・カルローニなどの多くのティチーノの建築家たちは、有機主義と呼ばれるものに特別な関心を寄せていました。しかし、彼らはティチーノの田舎の家々、特にアルプス地方にあるものにも魅力を感じていました。その基本的な幾何学の卓越した力強さ、見事な石積みの遂行、そして、これらのアルカイックな結晶体を風景の中に配置する際の極めて高い精度が、そこにあったからですね。一方で、彼らの野心は現代的な空間の質を追求することであり、またそれらの建物と環境とを調和させる方法をも模索していました。つまり、フランク・ロイド・ライトの建築は重要な参照系であったわけです。

ティチーノ州において、そのライト - モデルは二つの方面からもたらされたのです。イタリアからは、亜高山帯の州で多大な影響力と名声を博する批評家、そしてその広報者としてのブルーノ・ゼヴィの仕事を通して。チューリッヒからは、例えば、ヴェルナー・モーザーのモノグラフを通して。

モーザーは、タリアセンで働いた経験があり、1952年の巡回展「Sixty years of Living Architecture: the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright」のスイス展の際に、このモノグラフを出版して成功したわけですが。

ライト - モデルは現代的である一方、地理的のみならず、歴史的そして文化的な理解を踏まえながら、建物に根を与えて、しっかりとその特定の地域に建築を根付かせることを可能にしたのです。驚くべきことに、ティチーノの建築家たちは、それぞれ独自の方法でライトの作品を解釈しているのです。フランコ・ポンティの作品はライト - モデルに最もよく似ているものの一つかと思いますが、類似性という観点からだけ見ていても、表面的な理解にしかなりません。ポンティの作品は、模倣ではなく、独自の再解釈なのです。その最大の特徴は、形と空間に関する、個人的で厳格な文法への探求にあるのだと感じます。そこでの考えは、ポンティが彼のキャリアの初期に共に仕事をし、大きな影響を受けたティチーノ建築(ティチーノ建築以外でもそうですが)の巨匠、ペッポ・ブリビオから借りてきたものです。

この探求はとても困難なもので、というのも、それがポンティが戸建て住宅のみに焦点を当てた理由の一つでもあると思うのです。探求の対象を限定することで、建築の基本的なテーマに的を絞ることができ、理想へと近づくことができたのです。

ポンティの探求は極めて独自なものでしたし、個人的であり、自律的な、ましてやミステリアスなオブジェクトを生み出すことを目的としています。都市の建築を構築する必要性が強調されていた他の重要な運動に対して、ポンティの立場はどのように共存してたのでしょうか?

この時期のティチーノの建築家たちは、実に多様なアプローチをとっていました。ポンティは「反 - 都市」というラディカルな立場をとっていましたが、例えばこれはルイジ・スノッツィとは根本的に異なりますよね。スノッツィは1932年生まれです。(つまり、ポンティより11歳年下ですね)

彼は、彼の活動の最初期に有機主義 - モデルを見ていましたが、やがてティチーノ州の現実 - それは本質的に農村地域であるということ - をそのまま受け入れた建築に不満を持つようになり、広い意味での都市空間の構築に関心を向け、その関心を未だ都市的テーマが未明瞭な場所へと持ち込んでいったのです。ポンティは一方、こういった作業にはあまり関心がありませんでした。彼は、まるで「アルプスのアルカディア」というアイデアに導かれるようにして仕事に取組み、地方や農村の建築の伝統との対話を続けようとしたのです。

実際、ポンティは個人主義者でしたし、集団ではなく個人を信じていました。ポンティの関心の中心にあったのは、常に特定の個人であり、またその人の個性やニーズなのだったのです。同時に、創造的な独自性を重視し、それを実現する方法を模索していました。ですから、彼はライトの非常に有効なメタファー、住宅はクライアントの肖像である、をよく拝借していたのです。肖像画は、描かれた対象の魂を掴んでいくようなものですが、画家は常にそれを自分のやり方で描きますし、建築家は設計することで同じことを志しているのです。

しかし、ポンティの建築的文法は、それ自体が目的化した不合理な妄想ではないのです。

カズラノのサン・ミケーレ村をみてください。これは、文化的建設請負人、エリジオ・ボニが発案した先見性のある事業なのです。彼は、タミやカメンツィントと同世代の優れた建築家、アウグスト・ヤッグリに湖畔の区画整理の計画を依頼しました。ヤッグリは懸命にも、妥当な案、つまりその土地からは最大の利益を得ることのできる案を提案したのです。それから間も無く、ボニはポンティにたった6軒の住宅(最終的には8軒となったのですが。)を委託し、土地の大半に家を建てるというアイデアを一時的に断念することとしたのです。ボニと共にポンティが目指したのは、強い個性を持ちながらも、共通のボキャブラリーを持ち、お互いに対話を生み出すようなアンサンブルだったのです。

ポンティの建築は、同時代の人々にどのように受け入れられたのでしょうか?

ポンティの探求は、実に個人的なものであったので、ティチーノ界隈では常に評価されてはいましたが、例外として見られていて、おそらく刺激的なものであったとは思うのですが、孤立していたのでしょう。彼のキャリアは、若い建築家たちが有機主義 - モデルから離れようとして、ル・コルビュジエのような他の情報源に目を向けていた頃だったのです。有機的建築と合理的建築の風刺的な二分法をここで思い出したいわけではありません。なぜなら、そこには、逆にこれら二つの立場の充実した対話があったからです。ティタ・カルローニの作品のように。いずれにせよ、このことがポンティの作品が過小評価される原因となっているのかもしれません。彼は常に優れた建築家であり、非凡な職人であると考えられてはいましたが、彼の仲間たちに特別な影響を与えるようなことはありませんでした。

彼の手法における基本要素とは何なのでしょうか?

ポンティの作品において「タイプ」という概念が重要な役割を果たしていると思います。はて、「タイプ」という概念ほど「個性」と関係のないものはないのではないか?と思われるかもしれませんね。しかし実はこのコンセプトは、ジャン・カステックスが「Le printemps de la Prairie House」(1986年)で鋭く指摘しているように、ライトの建築の中核でもあるのです。

ポンティは、経験を積むにつれて結晶化させた、一連の基礎的構想からスタートし、限られたルールに基づく厳格な文法と明瞭な幾何学性を用いて、設計概要や敷地の特徴などの制約にぴったりと適した解決策を見つけることができたのです。ポンティは、どういった場合においても、完全に新しいものを生み出すということには興味がありませんでした。

形式的な文法の一貫性、そして先に述べたように、ほぼ戸建て住宅というテーマだけを扱うという決断が、ポンティの作品を分類学的に分別することを可能にしているのです。それぞれの建物は他の建物との共通点、あるいは相違点によってその価値を得るというわけです。これは(建築家にとっては歓迎すべき帰結ではないのですが)その住宅が一目で認識され得る、独特の「スタイル」(最もラディカルなモダニストたちが忌避する批判的なカテゴリーではありますが、一定の有用性もなくはないでしょう)を表明していることを意味するのです。

なぜ直交幾何学がそんなにも重要なのだと思われますか?

幾何学は、擬態することに甘んじることなく、景観に配慮した近代建築をデザインする方法です。ポンティの作品にはヴァナキュラーの模倣はなく、再解釈があるのです。それは全く異なることですね。彼の住宅は遠くから見ても目立つことはありません。近づくことで初めて、幾何学的な形状がゆっくりとその存在を明らかにしていくのです。このことは、この時代のティチーノの多くの建築家にとって共通の関心事でした。まず、ティタ・カルローニの「カーサ・バルメッリ」を取り上げてみましょう。ここでの幾何学は、傾斜地という特殊な場所の形と密接に関係しています。遠くからこの住宅を見分けることはとても難しいのです。過激な幾何学的秩序のために、周辺環境から突出して見えるはずだと思われるかもしれません。しかし、その逆なのです。建物の素材(主には木と石)によって、近づいて初めてその存在がはっきりと現れてくるのです。擬態するような方法ではなく、形式的に独立しており、言葉的にも明快であるにもかかわらず、至近距離で初めて存在感を示し、遠くからは周囲の環境との繊細な対話がなされているという点が面白いと思うのです。これは私たちが多くを学ぶことができる深く貴重な教訓です。このようにして、この地域には、まわりよりも大声で叫び、自らの貧しさを隠蔽するような建築ではなく、対話に励む建築が集まってくることになるのです。

フランコ・ポンティの家のシンプルさと豊かさには目を見張るものがありますね。カーサ・グラフは、例えば、石でできたボリュームの上に屋根が乗っかっているところなど、原始的なアルプスの小屋のプリミティブな特徴を体現していますね。

私もそう思います。でもあなたの説明と全く同じに、というわけではないので注意が必要ですよ。私がこの家を選んだのは、大きな違いを生成するような非常に精密な建築的判断があったからです。あなたは「石でできたボリュームの上に屋根が乗っかっている」とおっしゃったのですが、厳密にはそうではないのです。部屋を内包するボリュームを定義づける急勾配の屋根面は、基礎の花崗岩の石積みと重なり合って、連結したボリュームのイメージを生成しています。つまり、これが、ボリュームの分節的接続から住宅の最も細部のディテールのデザインに至るまで繰り返されるポンティの建築的ディスコースの真の姿なのです。

ここでは、正確な形式的帰結を得るために、全体的な構造計画が行われていることがわかります。ポンティは建設に関する豊富な知識を持ってたので、驚くべき解決策を開発することができたのです。それは注意深くデザインされたディテールに現れています。

この家のもう一つの重要な特徴である暖炉に注目してください。その暖炉のボリュームは中心の軸からわずかにずれて配置されていますね。この暖炉という装置によってエントランスの中庭が定義され、対抗する二つのコーナーウィンドウの間に、思いのほか強力な視覚的対角線が発生し、それらによってダイニングルームの空間と庭とが繋がれるのです。これが、モダンな性格を持った空間であることは明らかで、ヴァナキュラー - モデルとは何ら関係のないものなのです。

本質的なところまで削ぎ落とされながらも、貧相で取るに足らないようなものではなく、非常に限られた手段でもって極限的な空間の質に達するために考えられた、非常にシンプルなジェスチャーというものが、どれほど力強いものとなるのかには驚きますね。

ファサードと勾配屋根から煙突が突き出ている部分をよく見てください。下の部分が太くなっていますね。要素が上へ向かって先細りになっていくという考えを強調しているのですが、文字通り、煙突が地面から伸びて土地に根付いていくかのように、家をその場所に定着させる杭となり、その中心を象徴的に示しているのです。ところが、断面図をよく見ると、これが形式的なトリックであることに気付きます。屋根の上には、二つの鉄筋コンクリートの支持材があって石を支えているのです。これは、ポンティの建築においてはしばしば、プロジェクトに別次元での複雑さを加えるような、視覚的快楽や記号的特徴の探求によって決断がなされることがあることを示していますね。

ポンティの近代的な文法を構成するもう一つの要素は、ペッポ・ブリビオ(彼は新造形主義の建築からそのアイデアを借りてきています)から受け継いだ、壁を穿たないという原則なのです。例えば、ティタ・カルローニは、この原則を気にすることはありませんでしたが。ヴァナキュラー建築では、壁は常に開口部によって穿たれていますし、この種の原則は存在しないのです。しかしフランコ・ポンティの建築においては、開口部とは常に、明瞭に認識可能な要素間に残された空間のことであり、それが壁、床、あるいは屋根であれ、その配置によって、外部との正確な関係を決定しているのです。ポンティは、自身の建築の統語的一貫性に常に細心の注意を払っていました。

地面から生えてきたような重厚な石の塊と、その上に乗っかる軽快な木の構造物という二項対立はポンティの多くの建物に共通しています。このような形式的戦略の目的とは何だったのでしょうか?

そこには、地面に埋め込まれた(あるいは、ライトがよく言っていたように、敷地から生えてきた)塊がしっかりと屹立している、という考え方と、何かがぶさ下がったり、離れたりしているような軽さ、という考え方がありますよね。それはサン・ミケーレ村の家々を見れば明らかなことです。

ポンティはコントラストの探求をしていたのです。モルタルが隠蔽された非常に質の高い花崗岩の壁は、空積みの石壁を模していて、重量感を高めています。ところが、大工工事では対照的に、非物質的な印象を与えるためにも、断面積を減らして薄い金属を使ったりさえしていたのです。現場で撮影された写真に、重い石の塊の上に、蝶の羽のような屋根が繊細に乗っている美しいものがあります。石の塊は人工の地形であり、軽やかな構造物が着地する変形された地形なのですよね。この人工の地形の美しさと、それを取り囲む白樺には、胸を打つものがあります。オーギュスト・ペレの有名な言葉をも思い出させます。「建築とは美しい廃墟を作るものだ」と。ポンティの建築において、永久的なものは、すべて美しい廃墟的状態を目指しているように見えるのです。将来、住宅が寿命を迎えた時には、人工化された風景が現れて、地形としての概念に戻るように緻密に設計されているのです。人間の生活空間を規定するものは一時的なものであり、非常に緻密に建てられたものであっても、いつかは消えてしまうことへの責任を負っている。こういったコントラストはとても詩的なものだと思います。

ある意味、個人主義者になるための最もラディカルな方法は、慣例的な形式とは、形式的関連性を持たず、むしろもっと住まい手に最大の自由が与えられるような抽象的構造や構成の家に住むことだと思うのですが、家という空間がもつ本質的な「家庭性」についてはどうお考えですか?

私は特殊な環境で育ちましたし、その環境が家庭的空間に対する私の基本的な理解を決定的に形成しています。私の感覚では、家を意味論的に認識できるかどうかは問題ではありません。というのも、素晴らしく家庭的である空間の多くが、外観からは家にさえ見えないのです。

カーサ・グラフは、屋根の形からすぐに家だと認識できるのですが、ポンティの全ての住宅がそうだというわけではありません。例えば、私の両親の家はもっと抽象的ですし、家庭性とは、家というものから連想されるイメージに回帰することではないのです。私が面白いと思うのはポンティの家には様々な空間があることです。それらは、全てがフィルタリングされた景色の広がるオープンプランであることが多いのですが、正確で繊細な変化によって空間が結びつけられています。そのおかげで全体の空間の質が増幅しているのです。例えば、床から天井の高さの予期せぬ変化。それに何よりも室内への自然光の入り方。これらの特徴は、住宅の寸法に対する我々の認識を広げてくれるものです。ポンティの建物はどれも外観から想像するよりも、ずっと大きく見えるのです。このことはとても面白い特質だと思うのです。空間のそれぞれの部分が、ただ純粋に機能的なものとしてではなく、明確な行為へのニーズや、その瞬間や、景色に合わせて仕立てられているからです。それぞれの空間は、風景、開口部の種類、照明の度合い、そして他の空間との関係によって独自の性質を持っています。

例えば、カーサ・グラフでは、非常に明るい場所と、陰り、あるいは暗い場所とが絶えず入れ替わっていて、その違いは親密な空間と、風景へと向かう空間との違いのようなのです。私はこの寛容さがとても重要だと思いますし、こういった豊さが必要だと信じています。一つの家の中で、様々な空間体験、雰囲気や光の質の変化を享受できることは素晴らしいことだと思います。

私の育った家には、大きく、そして力強く連結された空間がありました。冬のリビングと夏のリビングのことです。そこにはそれぞれ固定式のソファが置かれていました。前者は暖炉に向かって、後者は風景を見渡すように配置されていたのです。その日の気分や何をするかによって、どちらかの空間を選ぶことができたことを覚えています。二つの空間があることで自由を妨げられていると思ったことはありません。

私はこれらの空間のことを、刻々と変化し続けるメロディーを奏でる楽譜のように考えていました。つまり、楽譜にはルールがありますが、演奏は好きなようにできますよね。それは必ずしも規制を意味するとは限らないということです。なぜなら、こういった空間でも誰もが好きなように自由に生活できるのですから。

カーサ・グラフと、有機的建築以外の建築作品との関連性を示すとしたら、どういったものが考えられるのでしょうか?

ライトへの言及は非常に強く、そのために他の何かと結びつけることは困難ではあるのですが、使用されている素材がティチーノ州の高山地域の建築を参考しているということに加えて、19世紀末のイギリスの居住文化(アーツ・アンド・クラフツ運動のことを考えているのですが。)に言及することはできるでしょう。フランク・ロイド・ライトの建築を育み、ご存知のようにヘルマン・ムテジウムによってドイツ語圏に広められた文化のことです。(アメリカンマスター、ライトがヨーロッパを周遊していた1910年に刊行された彼の偉大な作品集「ヴァスムート・ポートフォリオ」によって、ヨーロッパではライト作品が受容されるわけですが、そのいわば、土台が整えられていたということです)

総じて、ポンティが見ていたものとは、明るさと暗さのある空間が交互に現れたり、守られた感覚と解放された感覚とが調停されているような多様な感覚的体験を特徴とする、こういった家庭的空間の事例なのでしょう。

2021年2月6日

Nicola Navone: From 1969 to the early 1980s my father, Milo Navone, was a partner in the office of the architect Franco Ponti in Viganello. As a child I spent afternoons in their studio and from adolescence I lived in a house they designed and built.

I have chosen to speak about Casa Graf today, because it is the outcome of the research that Franco Ponti began in the 1950s in Villaggio San Michele at Caslano and represents a sort of a paradigm of his architecture. What has always impressed me, is the richness of its internal space and, at the same time, the simplicity of its layout, which can be described in a few words and condensed into a few signs. All this in a building that is small yet extremely generous. It conveys an idea of a domestic space that, I believe, played a crucial role in encouraging me to study architecture.

HOW DID YOUR FATHER MEET FRANCO PONTI AND WHAT IS THE STORY OF THEIR COLLABORATION?

My father got a position in Tita Carloni’s office in 1955. He recalled that every morning young architects (among them my father and a very young Mario Botta) had the duty to turn on the stoves and wake up Franco Ponti, who was usually found sleeping on three chairs (designed by Carloni) tied together.

He was a bit of a Bohemian. He used to go to night clubs where, apart from just having a good time, he also got to know his clients. In fact, he was always broke, not just because of the night life, but he was also very generous. Tita Carloni often put him up, and this is how my father and Ponti got to know each other. Their real collaboration, however, started later, in 1969, after a period spent by my father in Turin in Leonardo Mosso’s studio.

During their years in practice together, my father contributed to the design and supervision of building sites as well as organising the workflow, to avoid the unwelcome effects of Ponti’s sometimes unpredictable conduct. I should stress that Franco’s character did not imply professional negligence. On the contrary, he was very rigorous and passionate about his work, but he followed his moods and curiosity wherever they took him, and he was unrestrained by conventions. One effect of this was that he tended to spin out the time he spent working on his houses, and he would often return to lavish further care on them afterwards.

THOSE WERE INTERESTING TIMES IN TICINO.

From the 50s, many Ticinese architects, starting from Rino Tami and passing to the younger generation, for instance Tita Carloni, expressed a special interest in what was called organicism. But they also shared a fascination with Ticinese rural houses, especially in the Alpine region, for the outstanding force of their elementary geometry, the masterly execution of the magnificent stone masonry, and the extreme precision with which these archaic prisms were placed in the landscape. On the other hand, their ambition was to achieve a modern spatial quality, and they looked for ways to relate their buildings harmoniously to the context. Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture provided a crucial frame of reference.

In Ticino, Wrightian models came from two sides: from Italy, through the work of Bruno Zevi as a critic and publicist who enjoyed great influence and prestige in the subalpine canton, and from Zurich, for instance through the monograph by Werner Moser. He had worked in Taliesin and published that successful volume in 1952 on the occasion of the Swiss leg of the travelling exhibition “Sixty years of Living Architecture: the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright”.

The Wrightian model made it possible to be contemporary while giving buildings roots, embedding them firmly in a particular region, understood not just geographically but also historically and culturally. What is surprising and worth noticing, however, is the originality with which Ticinese architects interpreted FLW’s work, each in their own way. Although Franco Ponti’s oeuvre most closely resembles the Wrightian model, it would be superficial to see it only in terms of similarities. Ponti’s work was an original reinterpretation, not an imitation. I feel its most important feature is the investigation of a personal and rigorous grammar of forms and spaces, an idea which he borrowed from Peppo Brivio, a master of Ticinese architecture (and much else), whom Ponti worked with in the early stages of his career and who had a profound influence on him.

This research was difficult, and I believe this was also one of the reasons why Ponti decided to focus only on single-family houses. Limiting the field of investigation enabled him to focus on fundamental architectural topics and bring them to perfection.

HIS RESEARCH IS EXTREMELY INDIVIDUAL, AIMED AT PRODUCING PERSONAL, AUTONOMOUS, EVEN MYSTERIOUS OBJECTS. HOW DID PONTI’S POSITION COEXIST WITH OTHER IMPORTANT MOVEMENTS STRESSING THE NEED TO BUILD THE ARCHITECTURE OF A CITY?

The architects of this period in Ticino had substantially diverse approaches. Ponti had a radical “anti-urban” position, fundamentally different from Luigi Snozzi’s, for instance. Snozzi was born in 1932 (hence 11 years younger than Ponti).

He looked at the organicist model in the very early stages of his work. Soon, however, he was no longer satisfied with architecture that accepted the reality of Ticino as it had been – essentially a rural region – and began to direct his interests towards the construction of urban space, understood in the broadest sense, bringing urban themes to places where they were not yet articulated. Ponti, by contrast, was not deeply interested in this kind of operation. He worked as if guided by the idea of an “alpine arcadia”, trying to keep up a dialogue with local and rural building traditions.

In fact, Ponti was an individualist, who believed in individuals, not the collective. At the centre of Ponti’s interest was always a specific person, with his or her personality and needs. At the same time, he placed the emphasis on creative independence and sought ways to achieve it. For this reason, he also borrowed from FLW the very efficient metaphor of a house as a portrait of the client. A portrait grasps the soul of the subject painted, but the artist always paints it in his or her own way, and the architect aspires to do the same by designing.

Ponti’s search for an architectural grammar, however, was not an irrational obsession engaged in for its own sake. Consider Villaggio San Michele in Caslano. It was a far-sighted operation originated by the cultivated building contractor Eligio Boni. He asked Augusto Jäggli, an excellent architect from the generation of Tami and Camenzind, to draft a parcelling project for a plot on the lakeside, and Jäggli diligently presented him with a decent proposal, which nevertheless sought to make the most profit from the plot of land. Shortly after this, Boni decided to entrust Ponti with the design of only 6 houses there (in the end they became 8), temporarily giving up the idea of building on most of the land. Ponti’s ambition, shared by Boni, was an ensemble consisting of houses with a strong individual character, yet sharing a common vocabulary that would create a dialogue between them.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE RECEPTION OF HIS ARCHITECTURE BY HIS CONTEMPORARIES?

Ponti’s research was so personal that in the Ticinese panorama his work has always been appreciated, but seen as an exception, perhaps stimulating but isolated. Then his career came at the time when young architects wanted to move away from organic models and were looking at other sources like Le Corbusier. I don’t want to recall here the caricatural dichotomy between organic and rational architecture, since there was – on the contrary – a fruitful dialogue between these two positions, as in the work of Tita Carloni. All the same, this may have contributed to Ponti’s work being underrated. He was always considered a good architect, an extraordinary craftsman, yet without any particular influence on his colleagues.

WHAT WERE THE FUNDAMENTAL COMPONENTS OF HIS METHOD?

I think that in Ponti’s work the concept of the ‘type’ plays an important part. Now, you may ask what can be less related to the idea of “individuality” than the idea of “type”? But, in fact, this concept is also central to Wright’s architecture, as was perceptively shown by Jean Castex in Le printemps de la Prairie House (1986).

Starting from a series of basic schemes, which Ponti crystallised as he gained experience, and using a rigorous grammar based on a limited number of rules and characterised by a clear geometry, he was able to find solutions that were perfectly suited to the constraints of the brief and the features of the site. Ponti was not interested in inventing something completely new in every case.

The coherence of the formal grammar, and, as I have said, the decision to deal almost exclusively with the theme of the single-family house, make it possible to devise a taxonomic classification of his work, in which each building acquires a value by virtue of what it has in common with other buildings in the same series or what distinguishes it from them. This means (as a corollary not unwelcome to an architect) that his houses are immediately recognisable, manifesting a peculiar “style” (a critical category abhorred by the most radical Modernists, but not without a certain usefulness).

WHY WAS ORTHOGONAL GEOMETRY SO IMPORTANT?

Geometry was a way of designing modern architecture that cares for the landscape without indulging in mimesis. There is no imitation of the vernacular in Ponti’s work, there is a reinterpretation, which is quite different. His houses do not stand out from a distance. Only as you get closer does the geometry slowly reveal their presence. This was a common concern for many architects in Ticino in this period. Let’s take Casa Balmelli by Tita Carloni first. Geometry here is closely related to the landforms of a specific place, the sloping terrain. It is very difficult to make out the house from a distance. It might seem that because of its radical geometrical order it ought to be visible, standing out from its setting. The opposite is true. Its presence emerges clearly only when you come closer to it, thanks to its materials (mainly wood and stone). I find it interesting that he was able to make something that is not mimetic, that achieves formal independence and clarity of language, but which only becomes a distinct presence when seen fairly close up, while establishing a delicate dialogue with its surroundings from a distance. This is a profound and precious lesson that we can learn a lot from. In this way the region would end up being populated by buildings engaged in a dialogue, not by architecture that tries to mask its poverty by shouting louder than the others.

THE SIMPLICITY AND RICHNESS OF FRANCO PONTI’S HOUSES IS STRIKING. CASA GRAF MANAGES TO EMBODY THE PRIMITIVE CHARACTER OF PRIMORDIAL ALPINE HUTS: A ROOF RESTING ON VOLUMES MADE OF STONE.

I agree, but we need to be careful, as it is not exactly as you describe it. I chose this house also because of very precise architectural decisions that make a big difference. You said “a roof resting on volumes made of stone”. That’s not precisely true. The steeply sloping planes of the roof that define the volume housing the rooms overlap the granite masonry of the basement, generating the image of interlocked volumes: a true figure of Ponti’s architectural discourse, which recurs from the volumetric articulation to the design of the smallest details of his houses.

We can see that there is a whole constructional research here aimed at reaching a precise formal result. Ponti possessed significant constructional knowledge that enabled him to develop surprising solutions underlined by carefully designed details.

I would like to direct your attention to another important feature of this house: the fireplace, whose volume is set slightly off the central axis. Through this device the atrium of the entrance is defined, and an unexpected and extremely strong visual diagonal is created between two opposite corner windows, capable of linking the space of the dining room with the garden. It is clearly a space with a modern character, having nothing to do with vernacular models.

It is astonishing how strong a very simple gesture can become if one works to reduce it to essentials, not impoverishing or trivialising but striving to achieve an extraordinary spatial quality with very limited means.

Take a closer look at the facade and the point where the chimney projects from the pitched roof. It’s thicker in its lower part. This emphasises the idea of an element tapering towards the top, literally as if the chimney was growing out of the ground and rooting it to the land, becoming a peg anchoring the house to the place and symbolically marking its centre. If you look carefully at the section drawings, you realise that this is a formal trick. There are two consoles of reinforced concrete on the roof supporting the stones. It shows that in Ponti’s architecture there are often decisions driven rather by the search for visual comfort or semiotic features that add another level of complexity to the project.

Another component of Ponti’s modern grammar is the principle, taken from Peppo Brivio (who borrowed it from Neoplastic architecture), of never piercing a wall. Tita Carloni, for instance, never cared about this rule. In vernacular architecture the wall is always pierced by apertures, and no such principle of this kind exists. But in Franco Ponti’s architecture the apertures are always the spaces left between clearly recognisable elements which, by their arrangement, determine a precise relationship with the exterior, whether they are walls, slabs, or roofs. And Ponti is always extremely attentive to the syntactic coherence of his architecture.

THE DICHOTOMY OF A HEAVY STONE BLOCK GROWING OUT OF THE GROUND AND A LIGHT WOODEN STRUCTURE SITTING ON TOP OF IT IS COMMON TO A NUMBER OF PONTI’S BUILDINGS. WHAT WAS THE PURPOSE OF THIS FORMAL STRATEGY?

There is the idea of a mass embedded in the ground (or, as Wright used to say, growing out of the site) and standing firmly in place, and an idea of something hanging, detached, of lightness. This is very evident when we look at the houses in the Villaggio San Michele.

Ponti made a study of contrasts. The granite walls of exceptionally fine quality with concealed mortar to simulate a dry-stone wall heighten the impression of weight. In the carpentry work, by contrast, he sought to convey an impression of dematerialisation, even using metal profiles to reduce the sections. There are beautiful photos from the construction site showing the roofs like the wings of a butterfly resting delicately on the heavy blocks. It is an artificial topography, a modified terrain on which the light structures have landed. The beauty of this artificial topography together with the birches surrounding it, is striking. It also recalls Auguste Perret’s famous dictum, “Architecture is what makes beautiful ruins.” In Ponti’s architecture everything that is permanent seems to aspire to the status of a beautiful ruin. It is designed with such precision and care that in some future time, when the houses come to the end of their lives, it will appear an anthropised landscape and return to the idea of topography. What defines the space of human life could be temporary, built with extreme precision but liable to disappear one day. I find this contrast very poetic.

IN A SENSE, THE MOST RADICAL WAY TO BE AN INDIVIDUALIST WOULD BE TO LIVE IN A HOUSE THAT HAS NO FORMAL LINK TO CONVENTIONAL FORMS AND IS MORE LIKE AN ABSTRACT STRUCTURE OR COMPOSITION, ALLOWING ITS FULL APPROPRIATION BY THE USER. WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE INTRINSIC “DOMESTICITY” OF THE SPACE OF A HOUSE?

I grew up in a specific environment, that definitely formed my basic understanding of a domestic space. To my sensibility, it’s not a problem of the semantic recognisability of a house, because many incredibly domestic spaces don’t even look like houses from outside.

In Casa Graf it is immediately readable, because of the shape of the roof. But not all Ponti’s houses are like that. My parents’ house, for instance, is more abstract. It is not about returning to the imagery that we associate with the idea of a house. What I find interesting is the variety of spaces that we find in Ponti’s houses. They often have open plans where you have a filtered view of everything, yet their space is articulated through precise and subtle changes, that amplify the general spatial quality: unexpected shifts in the floor and ceiling heights, and most of all through the way natural light is brought indoors. These features help expand the perception of the dimensions of a house. Ponti’s buildings all look much larger than you expect them to be judging just from their external presence. And I believe this is a very interesting quality. They feel larger because each portion of space is tailored to the needs of a precise action, moment or view, yet without being purely functional. Each space has its own character created by its relationship with the landscape, the type of aperture, degree of illumination and the way they relate to the other spaces.

Casa Graf, for instance, constantly switches between very bright and shaded or darker areas, just like the difference between intimate spaces and ones projected towards the landscape. I find this generosity very important, and I believe in the necessity of this kind of richness. It’s wonderful that a house can offer an array of different spatial experiences, atmospheres and variable qualities of light.

In the house where I grew up there was a large, strongly articulated space, with a winter and a summer living room, each with a fixed sofa. The former was placed facing the fireplace and the latter looking out over the landscape. I remember that I could choose one of these two spaces depending on my mood or what I meant to do. I never felt that the fact of having these two spaces diminished my freedom. I treated it as a musical score on which I could play an ever-changing melody. A musical score has rules, but I play the music the way I want to. It is not necessarily a constraint; in this kind of space everyone is free to live as they please.

IF YOU HAD TO ESTABLISH A CONNECTION BETWEEN CASA GRAF AND OTHER WORKS OF ARCHITECTURE APART FROM ORGANICISM, WHAT WOULD YOU THINK OF?

The reference to Wright is so strong that it’s hard to connect it with other sources. But, in addition to the reference, in the materials used, to the architecture of the alpine regions of Ticino, we could mention the culture of the English dwelling at the end of the 19th century (I am thinking of the Arts & Crafts movement), which also nurtured Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture and was spread in the German area, as we know, by Hermann Muthesius (preparing the field, so to speak, for the reception of Wright’s work through the magnificent Wasmuth portfolio in 1910, on the occasion of the American master’s European trip). In general, I would say that Ponti looked at those examples of domestic space characterised by a great variety of sensory experiences, alternating bright and shadowy spaces and reconciling a sense of protection and at the same time openness to the landscape.

06.02.2021

尼古拉·纳沃乃: 1969年到八十年代初,我父亲,米罗·纳沃乃(Milo Navone),是在维加内罗(Viganello)的佛朗哥-庞蒂(Franco Ponti)事务所的一名合伙人。孩童时我在他们的工作室度过了一些下午,而从青春期开始,我住在一栋由他们设计和建造的住宅里。

我今天选择谈论格拉夫住宅(Casa Graf),因其是佛朗哥-庞蒂在20世纪50年代开始在卡斯拉诺(Caslano)的圣客米凯莱村(Villaggio San Michele)的研究的结果,代表了他的建筑的某种范式。一直来使我印象深刻的,是其内部空间的丰富,于此同时,布局上的简洁,能够被几个词语所描绘或浓缩为几个标志。所有这一切都在一个小而极其慷慨的建筑中。它传达了一种居家空间的理念,我相信,这种理念在激励我学习建筑方面起到了关键的作用。

你的父亲是怎么认识弗朗克客庞蒂的,他们的合作又有什么样的故事呢?

1955年,我父亲在蒂塔·卡洛尼(Tita Carloni)事务所获得了一个职位。他回忆说,每天早上年轻建筑师(其中有我父亲和年轻的马里奥·博塔(Mario Botta)要负责点燃炉子并叫醒弗朗克客庞蒂,通常会发现他睡在绑在一起的三张椅子上(由卡洛尼设计)。

他有点像个波西米亚人。他经常去夜店,享受了一段快乐时光之外,也认识了一些他的客户。事实上他总是身无分文,不仅因为夜生活,也因为他非常慷慨。蒂塔客卡洛尼经常让

他留宿,这就是我父亲和庞蒂认识的过程。

然而他们真正的合作,开始在之后, 1969年,在我父亲在都灵的莱昂纳多·莫索(Leonardo Mosso)事务所待了一段时间之后。

在他们共同实践的几年里,我父亲对设计、现场监工以及工作流程的组织做出了贡献,以避免庞蒂有时不可预测的行为造成不受欢迎的影响。我要强调一下,佛朗哥的性格并不意味着职业上的疏忽。相反,他对自己的工作非常严谨而热情,但他会追随自己的情绪和好奇心,无论被带向哪里,他都不受传统的约束。这样做的一个结果是,他倾向于把花在住宅上的时间挤出来,而且他经常在事后回来对房子进行进一步的维护。

那曾是提挈诺有趣的时代

从50年代起,许多提挈诺建筑师,从里诺-塔米(Rino Tami)开始,到年轻一代,例如蒂塔-卡洛尼,都对所谓的有机主义表现出特殊的兴趣。然而他们也对提挈诺的乡舍,特别是阿尔卑斯山区的,有着共同的迷恋,因其彰显的卓越力量,那来自原始几何形,来自宏伟的石头砌筑物的巧妙处决,以及来自这些古老的棱角置于景观中的极端精确性。另一方面,他们的志向在于获得现代性的空间质量,他们寻找方法将他们的建筑与环境和谐地联系起来。弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的建筑提供了一个关键性的参考框架。

在提契诺州,赖特的模式来自两方面:一是来自意大利,通过布鲁诺-泽维(Bruno Zevi)的工作,他是一位批评家和宣传家,在阿尔卑斯山州享有巨大的影响力和威望;二是来自苏黎世,例如通过维尔纳-莫泽(Werner Moser)的专著。

他曾在塔利辛(Taliesin)工作过,并在1952年 “活的建筑60年:弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的作品 “巡回展览的瑞士站时期出版了那本成功的书。

赖特的模式使得建筑在具有当代性的同时能够赋予建筑根基,将其牢牢地嵌入到一个特定的区域,不仅在地理上,而且在历史和文化上也能解读。然而,令人惊讶和值得注意的是,提挈诺建筑师以自己的方式诠释了赖特的工作,每个具有其独创性。尽管弗朗哥客庞蒂的作品与赖特的模式最为相似,但如果只从相似性的角度来看,那就太肤浅了。庞蒂的作品是一种原创的重新诠释,而不是模仿。我觉得它最重要的特点是对形式和空间的个人化且严格的语法的研究,这个想法是他从佩波-布里维奥(Peppo Brivio)那里借鉴来的,他是提契诺建筑(和其他很多东西)的大师,庞蒂在他职业生涯的早期阶段和他一起工作,对他有深刻的影响。

这项研究很困难,我相信这也是庞蒂决定只关注单一家庭住宅的原因之一。对研究领域的限制使他能够专注于基本的建筑主题,并使其达到完美的效果。

他的研究是非常个人化的,旨在制造个人的、自主的、甚至是神秘的物体。庞蒂的立场是如何与其他强调建造城市建筑需要的重要运动共存的?

这一时期提契诺州的建筑师们实质上的追求各不相同。例如,庞蒂有一个激进的 “反城市 “立场,与路易吉-斯诺齐(Luigi Snozzi)的立场有根本上的不同。斯诺齐生于1932年(因此比庞蒂年轻11岁)。

在他工作的早期阶段,他研究了有机主义模式。但很快,他就不再满足于接受建筑在提契诺州的现实——这基本上是一个农村——并开始将兴趣转向城市空间的建设,从最广泛的意义上理解,将城市主题带到尚未阐明的地方。相比之下,庞蒂对这种操作并不深感兴趣。他的工作仿佛是在 "阿尔卑斯山世外桃源 (alpine arcadia)"的理念指导下,试图与当地和乡村的建筑传统保持对话。

事实上,庞迪是一个个人主义者,他相信个人而不是集体。庞蒂的兴趣中心始终是一个具体的人,有他或她的个性和需求。同时,他把重点放在有创造力的独立性上,并寻求实现这种独立性的方法。出于这个原因,他还从赖特那里借用了一个非常有效的比喻:住宅是客户的画像。肖像画抓住了被画对象的灵魂,而艺术家总是以自己的方式作画,建筑师也渴望通过设计来做到这一点。

然而,庞蒂对建筑语法的探索并不是出于自身追求的非理性执迷。考虑到卡斯拉诺的圣客米凯莱村,这是由有修养的建筑承包商埃利吉奥-波尼(Eligio Boni)发起的一项有远见的行动。他请奥古斯托-雅格利(Augusto Jäggli),一位来自塔米和卡门辛德(Camenzind)那一代的优秀建筑师,为湖边的一块地的一个分包项目画草图,雅格利辛勤地向他提交了一个得体的方案,但还是想从这块土地上获取最大的利润。此后不久,波尼决定委托庞蒂在那里只设计6栋住宅(最后变成了8栋),暂时放弃了在大部分土地上建造的想法。庞蒂的雄心壮志,与波尼一样,是由具有强烈个性的住宅组成的集合体,但共享一个共同的语汇,这将在它们之间创造对话。

您如何描述同时代人对他的建筑的接受情况?

庞蒂的研究是如此的个人化,以至于在提契诺的全景视野中,他的作品一直获得欣赏,却被视为一个例外,也许令人受到启发,但却是孤立的。他那时的职业生涯正在年轻建筑师想要摆脱有机主义模型,并且正在寻找其他来源,如勒-柯布西耶的时候。我不想在这里回顾有机建筑和理性建筑之间滑稽的二分法,因为恰恰相反,这两种立场之间存在着富有成效的对话,比如在蒂塔-卡洛尼的作品中。尽管如此,这可能导致了庞蒂的作品被低估。他一直被认为是一个优秀的建筑师,非凡的工匠,但对他的同侪们没有任何特别的影响。

他的方式的基本组成部分是什么

我认为,在庞蒂的作品中,"类别 "的概念起着重要的作用。现在,你可能会问,还有什么能比 "类别 "的想法与 "个性 "的想法更不相关呢?但事实上,这个概念也是赖特建筑的核心,正如让-卡斯特克斯(Jean Castex)在《草原之家(Le printemps de la Prairie House)》 (1986)中敏锐地标示的那样。

从一系列的基本策略(scheme)开始,庞蒂随着经验的积累将这些策略具象化,并使用基于有限规则和清晰几何形的严格语法,他得以找到完全适应任务书限制和场地特点的解决方案。对于在每个案例中创造全新的东西,庞蒂不感兴趣。

由于其形式语法的连贯性,以及几乎只处理单一家庭住宅这一主题的设计决策(如我所述),使得我们有为他的作品设计分类法的可能性。在这个分类法中,根据它与同系列其他建筑的共同点或与之的区别点,每座建筑可以获得一定的价值。这意味着(对建筑师来说一个不愉快的必然结果),他的房子是可以被立即识别的,表现出一种独特的 "风格"(被最激进的现代主义者所厌恶的评判类别,但并非没有某种用途)。

为什么正交几何如此重要?

几何学是设计现代建筑的一种方式,它关心景观而不沉溺于模仿。在庞蒂的作品中,没有对乡土的模仿,有的是一种重新诠释,这是有极大区别的。他的房子从远处看并不显眼。只有当你走近时,几何形才会慢慢显示出它们的存在。这也是这一时期提契诺州许多建筑师共同的关注点。我们先来看看蒂塔-卡罗尼的巴尔梅利住宅(Casa Balmelli)。这里的几何学与特定的地貌,即倾斜的地形密切相关。从远处看很难看出这个房子。似乎由于其激进的几何秩序,它应当是显眼的,从环境中脱颖而出。然而事实恰恰相反。只有当你走近它时,它的存在才会清晰地浮现,这要归功于它的材料(主要是木材和石头)。我觉得有趣的是,他能够创造出一些没有模仿的东西,实现形式上的独立和语言上的清晰,但只有在相当近的地方观察时才会成为一个鲜明的存在,同时从远处又与周围的环境建立起微妙的对话。这是一堂深刻而宝贵的课程,我们可以从中学到很多。通过这种方式,聚集于此地的最终会是参与对话的建筑,而不是那些试图通过更大声的呼喊来掩盖其自身贫乏的建筑。

弗朗科-庞蒂住宅的简单和丰富令人震惊。格拉夫住宅成功地体现了原始阿尔卑斯山小屋的特征。屋顶安放在石头的体量上。

我同意,但我们需要小心,因为它并不完全像你描述的那样。我选择这所住宅也是因为非常精确的建筑决定会形成很大的不同。你说:"屋顶放在石头做的体量上"。这并不完全正确。屋顶陡峭的斜面定义了房间的体积,与地下室的花岗岩砖石重叠,产生了体量互锁的图像:这是庞蒂建筑论述的真实写照,从体量的衔接到他房屋的最小细节的设计,都是如此。

我们可以看到,这里有着整体的建造研究,旨在达到一个精确的形式结果。庞蒂拥有重要的建筑知识,使他能够通过精心设计的细节来发展出令人惊讶的解决方案。

我想将你的注意力引向这所住宅的另一个重要节点:壁炉,其体量略微偏离中轴线。通过这个装置,入口处的中庭被定义,在两个相对的角窗之间形成了一个意想不到的、极其强烈的视觉对角线,能够将餐厅的空间与花园联系起来。这显然是一个具有现代特征的空间,与乡土模型毫无关系。

令人惊讶的是,如果人们努力将一个很简单的姿态削减到本质,它可以变得如此强大,不是贫乏或琐碎,而是努力以极为有限的手段实现非凡的空间质量。

仔细看看外墙和烟囱从斜屋顶上伸出来的地方。它的下部比较厚。这强调了一个元素向顶部逐渐变小的想法,从字面上看,就像烟囱从地面上长出来并扎根于土地,成为一个钉子,将房子固定在这个地方,并象征性地标记其中心。如果仔细看一下剖面图,你会意识到这是一种形式上的技巧。屋顶上有两个钢筋混凝土的支柱,支撑着这些石头。这表明,在庞蒂的建筑中,往往有一些决策驱使于寻求视觉舒适性或符号学特征,这些特征为项目增加了另一个层次的复杂性。

庞蒂的现代性语法的另一个组成部分取自佩波-布里维奥(他从新古典主义建筑中借用)的原则,即永远不要刺穿墙壁。例如,蒂塔-卡洛尼就从不关心这一规则。在乡土建筑中,墙壁总是被开孔穿透,不存在这样的原则。但在佛朗哥-庞蒂的建筑中,孔洞总是明晰的元素之间的空隙,这些元素经过排布,确定了建筑与外部的精确关系,不论它们是墙壁、楼板还是屋顶。庞蒂总是非常注意他的建筑的句法一致性。

庞蒂的许多建筑都有这样的特点:沉重的石块从地下长出,而轻盈的木质结构坐落于上,这种二分法很常见。这种形式策略的目的是什么?

在这里,有一种嵌入地面(或如赖特常说的,从场地中生长出来)并牢固地站在原地的想法,也有一种悬挂的、分离的、轻盈的想法。当我们看到圣客米凯莱村的住宅时,这一点就非常明显了。

庞蒂做了一项对比研究。品质卓越的花岗岩墙,用将砂浆遮蔽的方式来模拟干砌墙,增加了重量感。相比之下,在木作中,他试图传达一种非物质化的印象,甚至使用金属型材来减少截面。一些施工现场的美好照片显示,屋顶就像蝴蝶的翅膀一样,精妙地停留在沉重的砖块上。这一轻型结构坐落于一处由自然地形改造而来的人造基础之上。改造后的场所融合进了周围的白桦树林,获得了别样的美感。它也让人想起奥古斯特客佩雷的箴言:“建筑是创造美丽的废墟”。在庞蒂的建筑中,所有永久性的东西似乎都渴望成为美丽的废墟。它被设计得如此精确和谨慎,以至于在未来的某个时候,当房屋的寿命结束时,它将成为一个留有人类痕迹的景观,并回归到纯粹的地形学概念。尽管极端地精心设计与建造,那些定义人类生活空间的东西,依旧是有时效性的,终有一天会消失。我感觉这对比是非常有诗意的。

从某种意义上说,成为个人主义者的最激进的方式是住在一个与传统形式没有联系的住宅里,它更像一个抽象的结构或构图,允许使用者完全占有它。你对住宅空间的内在 "居家性 "怎么看?

我在一个特定的环境中长大,这无疑形成了我对家庭空间的基本理解。在我的感觉中,这不是一个住宅语意的识别性的问题,因为许多令人难以置信的居家空间从外面看甚至都不像住宅。

在格拉夫住宅中居家性是可以立即被读出来的,由于屋顶的形状。但不是所有庞蒂的住宅都是这样的。例如,我父母的住宅,是更抽象的。这并不是要回到我们与住宅的概念相关的意象。我发现有趣的是,我们在庞蒂的住宅里发现了各种各样的空间。它们通常有开放的平面,你可以看到所有的东西,然而这些空间是通过精确和微妙的变化来阐述的,像是放大了普通的空间质量:地板和天花板高度的意外变化,以及最重要的是通过自然光被引入室内的方式。这些特点有助于扩大人们对房屋尺寸的感知。仅仅从外观表现来判断,庞蒂的建筑看起来都比你预期的大得多。而我认为这是一个非常有趣的品质。感觉更大是因为每一部分空间都是根据精确的行动、时刻或景观的需要而定制的,但又不纯粹是功能性的。每个空间都有自己的特点,由其与景观的关系、孔洞的类型、照明的程度以及它们与其他空间的关系所创造。

例如,格拉夫住宅,在非常明亮和阴影或较暗的区域之间不断切换,就像私密的空间和向风景投射的空间之间的区别。我觉得这种慷慨是非常重要的,而且我相信这种丰富性的必要性。一所房子可以提供一系列不同的空间体验、气氛和可变的光线质量,这是绝妙的。

在我长大的房子里,有一个大的、强有力衔接的空间,有一个冬天的和一个夏天的客厅,其中都有一个固定的沙发。前者面对着壁炉,后者望向外面的风景。我记得我可以根据我的心情或我想做的事情,在这两个空间中选择一个。我从来不觉得拥有这两个空间的事实削弱了我的自由。

我把它当作一个乐谱,我可以在上面演奏不断变化的旋律。乐谱有规则,但我以我想要的方式演奏音乐。

这不一定是一种约束;在这种空间里,每个人都可以自由地生活,随心所欲。

如果要你在格拉夫住宅和有机主义以外的其他建筑作品之间建立联系,你会想到什么?

对赖特的参考是如此强烈,以至于很难将其与其他来源联系起来。但是,除了在所使用的材料中提到提契诺州阿尔卑斯山地区的建筑外,我们还可以提到19世纪末的英国住宅文化(我想到的是工艺美术运动),它也培养了弗兰克-劳埃德-赖特的建筑,并在德国地区传播,正如我们所知,由赫尔曼-穆特希斯(Hermann Muthesius)(可以说是通过1910年美国大师欧洲之行时,非凡的沃斯默思作品集(Wasmuth portfolio)为接受赖特的作品准备了场合)。总的来说,我想说的是,庞蒂关注的是那些以巨大的感官体验为特征的家庭空间的例子,明亮和阴暗的空间交替出现,调和了保护感和同时对景观的开放。

2021年2月6日

ニコラ・ナヴォーネ: 1969年から1980年代の初頭まで、私の父ミロ・ナヴォーネはヴィガネッロの建築家フランコ・ポンティの事務所でパートナーを務めていました。私が子供の頃は、彼らのスタジオで午後はいつも過ごしていましたし、思春期には彼らが設計し建てた家に住んでいました。

今日、カーサ・グラフについてお話することにしたのは、それがフランコ・ポンティが1950年代にカズラノのサン・ミケーレ村で始めた探求の成果であり、彼の建築の典型のようなものだからです。私がいつも感銘を受けるのは、その内部空間の豊かさと同時に、そのレイアウトのシンプルさなのです。それは少しの言葉で記述されたり、少しの記号に凝縮され得るものなのです。小さくても非常に寛大なこの建物の中には、これらの全てがあるのです。それは私に家庭的空間の考え方を伝えてくれましたし、私が建築を学ぶきっかけとなった重要な役割を果たしていたと思います。

お父様とフランコ・ポンティとの出会いや、お二人のコラボレーションについて教えていただけますか?

私の父は、1955年にティタ・カルローニの事務所で職を得ました。若い建築家たち(その中には私の父や、とても若いころのマリオ・ボッタがいました)には、ストーブに火をつけ、いつも椅子(カルローニのデザインでした)を三つひっつけて眠っているフランコ・ポンティを起こすという仕事があったんだよ、と父は回想していました。

彼は、ちょっとしたボヘミアンみたいなもので、よくナイトクラブに行き、そこで楽しい時間を過ごすだけでなく、クライアントとも知り合いになっていたのです。実際、彼はいつも一文無しでしたが、夜の生活のせい、というわけではなく、本当に寛大な人でしたから。ティタ・カルローニが彼をよく泊めていたこともあり、私の父とポンティはこうして知り合いになったのです。

ただ、彼らの本格的なコラボレーションは、父がトリノのレオナルド・モッソのスタジオで過ごした後の1969年以降に始まったことでした。

二人がともに仕事をしていた頃は、私の父は設計と現場監督、そしてワークフローの整理をしていました。それは、ポンティの時折起こす予測不能な行動がもたらす面倒な影響を避けるためなのですが。いや、フランコの性格が仕事上の過失を意味するものではないことは強調しておくべきですね。逆に、彼は仕事に対してとても厳格で情熱的でしたが、気分や好奇心の赴くままに行動したり、慣習に縛られることがありませんでした。そんな影響もあってか、家の設計に費やす時間をいつも引き伸ばしがちで、その後、作業に戻ってきてはさらに手を加えることが多かったようです。

この頃のティチーノは面白い時代でしたよね。

50年代に入ると、リノ・タミから始まり、その後の若い世代、例えばティタ・カルローニなどの多くのティチーノの建築家たちは、有機主義と呼ばれるものに特別な関心を寄せていました。しかし、彼らはティチーノの田舎の家々、特にアルプス地方にあるものにも魅力を感じていました。その基本的な幾何学の卓越した力強さ、見事な石積みの遂行、そして、これらのアルカイックな結晶体を風景の中に配置する際の極めて高い精度が、そこにあったからですね。一方で、彼らの野心は現代的な空間の質を追求することであり、またそれらの建物と環境とを調和させる方法をも模索していました。つまり、フランク・ロイド・ライトの建築は重要な参照系であったわけです。

ティチーノ州において、そのライト - モデルは二つの方面からもたらされたのです。イタリアからは、亜高山帯の州で多大な影響力と名声を博する批評家、そしてその広報者としてのブルーノ・ゼヴィの仕事を通して。チューリッヒからは、例えば、ヴェルナー・モーザーのモノグラフを通して。

モーザーは、タリアセンで働いた経験があり、1952年の巡回展「Sixty years of Living Architecture: the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright」のスイス展の際に、このモノグラフを出版して成功したわけですが。

ライト - モデルは現代的である一方、地理的のみならず、歴史的そして文化的な理解を踏まえながら、建物に根を与えて、しっかりとその特定の地域に建築を根付かせることを可能にしたのです。驚くべきことに、ティチーノの建築家たちは、それぞれ独自の方法でライトの作品を解釈しているのです。フランコ・ポンティの作品はライト - モデルに最もよく似ているものの一つかと思いますが、類似性という観点からだけ見ていても、表面的な理解にしかなりません。ポンティの作品は、模倣ではなく、独自の再解釈なのです。その最大の特徴は、形と空間に関する、個人的で厳格な文法への探求にあるのだと感じます。そこでの考えは、ポンティが彼のキャリアの初期に共に仕事をし、大きな影響を受けたティチーノ建築(ティチーノ建築以外でもそうですが)の巨匠、ペッポ・ブリビオから借りてきたものです。

この探求はとても困難なもので、というのも、それがポンティが戸建て住宅のみに焦点を当てた理由の一つでもあると思うのです。探求の対象を限定することで、建築の基本的なテーマに的を絞ることができ、理想へと近づくことができたのです。

ポンティの探求は極めて独自なものでしたし、個人的であり、自律的な、ましてやミステリアスなオブジェクトを生み出すことを目的としています。都市の建築を構築する必要性が強調されていた他の重要な運動に対して、ポンティの立場はどのように共存してたのでしょうか?

この時期のティチーノの建築家たちは、実に多様なアプローチをとっていました。ポンティは「反 - 都市」というラディカルな立場をとっていましたが、例えばこれはルイジ・スノッツィとは根本的に異なりますよね。スノッツィは1932年生まれです。(つまり、ポンティより11歳年下ですね)

彼は、彼の活動の最初期に有機主義 - モデルを見ていましたが、やがてティチーノ州の現実 - それは本質的に農村地域であるということ - をそのまま受け入れた建築に不満を持つようになり、広い意味での都市空間の構築に関心を向け、その関心を未だ都市的テーマが未明瞭な場所へと持ち込んでいったのです。ポンティは一方、こういった作業にはあまり関心がありませんでした。彼は、まるで「アルプスのアルカディア」というアイデアに導かれるようにして仕事に取組み、地方や農村の建築の伝統との対話を続けようとしたのです。

実際、ポンティは個人主義者でしたし、集団ではなく個人を信じていました。ポンティの関心の中心にあったのは、常に特定の個人であり、またその人の個性やニーズなのだったのです。同時に、創造的な独自性を重視し、それを実現する方法を模索していました。ですから、彼はライトの非常に有効なメタファー、住宅はクライアントの肖像である、をよく拝借していたのです。肖像画は、描かれた対象の魂を掴んでいくようなものですが、画家は常にそれを自分のやり方で描きますし、建築家は設計することで同じことを志しているのです。

しかし、ポンティの建築的文法は、それ自体が目的化した不合理な妄想ではないのです。

カズラノのサン・ミケーレ村をみてください。これは、文化的建設請負人、エリジオ・ボニが発案した先見性のある事業なのです。彼は、タミやカメンツィントと同世代の優れた建築家、アウグスト・ヤッグリに湖畔の区画整理の計画を依頼しました。ヤッグリは懸命にも、妥当な案、つまりその土地からは最大の利益を得ることのできる案を提案したのです。それから間も無く、ボニはポンティにたった6軒の住宅(最終的には8軒となったのですが。)を委託し、土地の大半に家を建てるというアイデアを一時的に断念することとしたのです。ボニと共にポンティが目指したのは、強い個性を持ちながらも、共通のボキャブラリーを持ち、お互いに対話を生み出すようなアンサンブルだったのです。

ポンティの建築は、同時代の人々にどのように受け入れられたのでしょうか?

ポンティの探求は、実に個人的なものであったので、ティチーノ界隈では常に評価されてはいましたが、例外として見られていて、おそらく刺激的なものであったとは思うのですが、孤立していたのでしょう。彼のキャリアは、若い建築家たちが有機主義 - モデルから離れようとして、ル・コルビュジエのような他の情報源に目を向けていた頃だったのです。有機的建築と合理的建築の風刺的な二分法をここで思い出したいわけではありません。なぜなら、そこには、逆にこれら二つの立場の充実した対話があったからです。ティタ・カルローニの作品のように。いずれにせよ、このことがポンティの作品が過小評価される原因となっているのかもしれません。彼は常に優れた建築家であり、非凡な職人であると考えられてはいましたが、彼の仲間たちに特別な影響を与えるようなことはありませんでした。

彼の手法における基本要素とは何なのでしょうか?

ポンティの作品において「タイプ」という概念が重要な役割を果たしていると思います。はて、「タイプ」という概念ほど「個性」と関係のないものはないのではないか?と思われるかもしれませんね。しかし実はこのコンセプトは、ジャン・カステックスが「Le printemps de la Prairie House」(1986年)で鋭く指摘しているように、ライトの建築の中核でもあるのです。

ポンティは、経験を積むにつれて結晶化させた、一連の基礎的構想からスタートし、限られたルールに基づく厳格な文法と明瞭な幾何学性を用いて、設計概要や敷地の特徴などの制約にぴったりと適した解決策を見つけることができたのです。ポンティは、どういった場合においても、完全に新しいものを生み出すということには興味がありませんでした。

形式的な文法の一貫性、そして先に述べたように、ほぼ戸建て住宅というテーマだけを扱うという決断が、ポンティの作品を分類学的に分別することを可能にしているのです。それぞれの建物は他の建物との共通点、あるいは相違点によってその価値を得るというわけです。これは(建築家にとっては歓迎すべき帰結ではないのですが)その住宅が一目で認識され得る、独特の「スタイル」(最もラディカルなモダニストたちが忌避する批判的なカテゴリーではありますが、一定の有用性もなくはないでしょう)を表明していることを意味するのです。

なぜ直交幾何学がそんなにも重要なのだと思われますか?

幾何学は、擬態することに甘んじることなく、景観に配慮した近代建築をデザインする方法です。ポンティの作品にはヴァナキュラーの模倣はなく、再解釈があるのです。それは全く異なることですね。彼の住宅は遠くから見ても目立つことはありません。近づくことで初めて、幾何学的な形状がゆっくりとその存在を明らかにしていくのです。このことは、この時代のティチーノの多くの建築家にとって共通の関心事でした。まず、ティタ・カルローニの「カーサ・バルメッリ」を取り上げてみましょう。ここでの幾何学は、傾斜地という特殊な場所の形と密接に関係しています。遠くからこの住宅を見分けることはとても難しいのです。過激な幾何学的秩序のために、周辺環境から突出して見えるはずだと思われるかもしれません。しかし、その逆なのです。建物の素材(主には木と石)によって、近づいて初めてその存在がはっきりと現れてくるのです。擬態するような方法ではなく、形式的に独立しており、言葉的にも明快であるにもかかわらず、至近距離で初めて存在感を示し、遠くからは周囲の環境との繊細な対話がなされているという点が面白いと思うのです。これは私たちが多くを学ぶことができる深く貴重な教訓です。このようにして、この地域には、まわりよりも大声で叫び、自らの貧しさを隠蔽するような建築ではなく、対話に励む建築が集まってくることになるのです。

フランコ・ポンティの家のシンプルさと豊かさには目を見張るものがありますね。カーサ・グラフは、例えば、石でできたボリュームの上に屋根が乗っかっているところなど、原始的なアルプスの小屋のプリミティブな特徴を体現していますね。

私もそう思います。でもあなたの説明と全く同じに、というわけではないので注意が必要ですよ。私がこの家を選んだのは、大きな違いを生成するような非常に精密な建築的判断があったからです。あなたは「石でできたボリュームの上に屋根が乗っかっている」とおっしゃったのですが、厳密にはそうではないのです。部屋を内包するボリュームを定義づける急勾配の屋根面は、基礎の花崗岩の石積みと重なり合って、連結したボリュームのイメージを生成しています。つまり、これが、ボリュームの分節的接続から住宅の最も細部のディテールのデザインに至るまで繰り返されるポンティの建築的ディスコースの真の姿なのです。

ここでは、正確な形式的帰結を得るために、全体的な構造計画が行われていることがわかります。ポンティは建設に関する豊富な知識を持ってたので、驚くべき解決策を開発することができたのです。それは注意深くデザインされたディテールに現れています。

この家のもう一つの重要な特徴である暖炉に注目してください。その暖炉のボリュームは中心の軸からわずかにずれて配置されていますね。この暖炉という装置によってエントランスの中庭が定義され、対抗する二つのコーナーウィンドウの間に、思いのほか強力な視覚的対角線が発生し、それらによってダイニングルームの空間と庭とが繋がれるのです。これが、モダンな性格を持った空間であることは明らかで、ヴァナキュラー - モデルとは何ら関係のないものなのです。

本質的なところまで削ぎ落とされながらも、貧相で取るに足らないようなものではなく、非常に限られた手段でもって極限的な空間の質に達するために考えられた、非常にシンプルなジェスチャーというものが、どれほど力強いものとなるのかには驚きますね。

ファサードと勾配屋根から煙突が突き出ている部分をよく見てください。下の部分が太くなっていますね。要素が上へ向かって先細りになっていくという考えを強調しているのですが、文字通り、煙突が地面から伸びて土地に根付いていくかのように、家をその場所に定着させる杭となり、その中心を象徴的に示しているのです。ところが、断面図をよく見ると、これが形式的なトリックであることに気付きます。屋根の上には、二つの鉄筋コンクリートの支持材があって石を支えているのです。これは、ポンティの建築においてはしばしば、プロジェクトに別次元での複雑さを加えるような、視覚的快楽や記号的特徴の探求によって決断がなされることがあることを示していますね。

ポンティの近代的な文法を構成するもう一つの要素は、ペッポ・ブリビオ(彼は新造形主義の建築からそのアイデアを借りてきています)から受け継いだ、壁を穿たないという原則なのです。例えば、ティタ・カルローニは、この原則を気にすることはありませんでしたが。ヴァナキュラー建築では、壁は常に開口部によって穿たれていますし、この種の原則は存在しないのです。しかしフランコ・ポンティの建築においては、開口部とは常に、明瞭に認識可能な要素間に残された空間のことであり、それが壁、床、あるいは屋根であれ、その配置によって、外部との正確な関係を決定しているのです。ポンティは、自身の建築の統語的一貫性に常に細心の注意を払っていました。

地面から生えてきたような重厚な石の塊と、その上に乗っかる軽快な木の構造物という二項対立はポンティの多くの建物に共通しています。このような形式的戦略の目的とは何だったのでしょうか?

そこには、地面に埋め込まれた(あるいは、ライトがよく言っていたように、敷地から生えてきた)塊がしっかりと屹立している、という考え方と、何かがぶさ下がったり、離れたりしているような軽さ、という考え方がありますよね。それはサン・ミケーレ村の家々を見れば明らかなことです。

ポンティはコントラストの探求をしていたのです。モルタルが隠蔽された非常に質の高い花崗岩の壁は、空積みの石壁を模していて、重量感を高めています。ところが、大工工事では対照的に、非物質的な印象を与えるためにも、断面積を減らして薄い金属を使ったりさえしていたのです。現場で撮影された写真に、重い石の塊の上に、蝶の羽のような屋根が繊細に乗っている美しいものがあります。石の塊は人工の地形であり、軽やかな構造物が着地する変形された地形なのですよね。この人工の地形の美しさと、それを取り囲む白樺には、胸を打つものがあります。オーギュスト・ペレの有名な言葉をも思い出させます。「建築とは美しい廃墟を作るものだ」と。ポンティの建築において、永久的なものは、すべて美しい廃墟的状態を目指しているように見えるのです。将来、住宅が寿命を迎えた時には、人工化された風景が現れて、地形としての概念に戻るように緻密に設計されているのです。人間の生活空間を規定するものは一時的なものであり、非常に緻密に建てられたものであっても、いつかは消えてしまうことへの責任を負っている。こういったコントラストはとても詩的なものだと思います。

ある意味、個人主義者になるための最もラディカルな方法は、慣例的な形式とは、形式的関連性を持たず、むしろもっと住まい手に最大の自由が与えられるような抽象的構造や構成の家に住むことだと思うのですが、家という空間がもつ本質的な「家庭性」についてはどうお考えですか?

私は特殊な環境で育ちましたし、その環境が家庭的空間に対する私の基本的な理解を決定的に形成しています。私の感覚では、家を意味論的に認識できるかどうかは問題ではありません。というのも、素晴らしく家庭的である空間の多くが、外観からは家にさえ見えないのです。

カーサ・グラフは、屋根の形からすぐに家だと認識できるのですが、ポンティの全ての住宅がそうだというわけではありません。例えば、私の両親の家はもっと抽象的ですし、家庭性とは、家というものから連想されるイメージに回帰することではないのです。私が面白いと思うのはポンティの家には様々な空間があることです。それらは、全てがフィルタリングされた景色の広がるオープンプランであることが多いのですが、正確で繊細な変化によって空間が結びつけられています。そのおかげで全体の空間の質が増幅しているのです。例えば、床から天井の高さの予期せぬ変化。それに何よりも室内への自然光の入り方。これらの特徴は、住宅の寸法に対する我々の認識を広げてくれるものです。ポンティの建物はどれも外観から想像するよりも、ずっと大きく見えるのです。このことはとても面白い特質だと思うのです。空間のそれぞれの部分が、ただ純粋に機能的なものとしてではなく、明確な行為へのニーズや、その瞬間や、景色に合わせて仕立てられているからです。それぞれの空間は、風景、開口部の種類、照明の度合い、そして他の空間との関係によって独自の性質を持っています。

例えば、カーサ・グラフでは、非常に明るい場所と、陰り、あるいは暗い場所とが絶えず入れ替わっていて、その違いは親密な空間と、風景へと向かう空間との違いのようなのです。私はこの寛容さがとても重要だと思いますし、こういった豊さが必要だと信じています。一つの家の中で、様々な空間体験、雰囲気や光の質の変化を享受できることは素晴らしいことだと思います。

私の育った家には、大きく、そして力強く連結された空間がありました。冬のリビングと夏のリビングのことです。そこにはそれぞれ固定式のソファが置かれていました。前者は暖炉に向かって、後者は風景を見渡すように配置されていたのです。その日の気分や何をするかによって、どちらかの空間を選ぶことができたことを覚えています。二つの空間があることで自由を妨げられていると思ったことはありません。

私はこれらの空間のことを、刻々と変化し続けるメロディーを奏でる楽譜のように考えていました。つまり、楽譜にはルールがありますが、演奏は好きなようにできますよね。それは必ずしも規制を意味するとは限らないということです。なぜなら、こういった空間でも誰もが好きなように自由に生活できるのですから。

カーサ・グラフと、有機的建築以外の建築作品との関連性を示すとしたら、どういったものが考えられるのでしょうか?

ライトへの言及は非常に強く、そのために他の何かと結びつけることは困難ではあるのですが、使用されている素材がティチーノ州の高山地域の建築を参考しているということに加えて、19世紀末のイギリスの居住文化(アーツ・アンド・クラフツ運動のことを考えているのですが。)に言及することはできるでしょう。フランク・ロイド・ライトの建築を育み、ご存知のようにヘルマン・ムテジウムによってドイツ語圏に広められた文化のことです。(アメリカンマスター、ライトがヨーロッパを周遊していた1910年に刊行された彼の偉大な作品集「ヴァスムート・ポートフォリオ」によって、ヨーロッパではライト作品が受容されるわけですが、そのいわば、土台が整えられていたということです)

総じて、ポンティが見ていたものとは、明るさと暗さのある空間が交互に現れたり、守られた感覚と解放された感覚とが調停されているような多様な感覚的体験を特徴とする、こういった家庭的空間の事例なのでしょう。

2021年2月6日

Nicola Navone: From 1969 to the early 1980s my father, Milo Navone, was a partner in the office of the architect Franco Ponti in Viganello. As a child I spent afternoons in their studio and from adolescence I lived in a house they designed and built.